Ms. Prynne, in a hall of mirrors

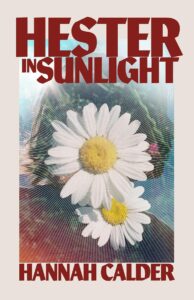

Hester in Sunlight

by Hannah Calder

Vancouver: New Star, 2024

$22.00 / 9781554202102

Reviewed by Candace Fertile

*

The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic nineteenth-century American novel about Hester Prynne, provides a kind of basis for Hester in Sunlight by Vernon resident Hannah Calder. But Calder (Piranesi’s Figures) moves far beyond a retelling or reinterpretation into metafiction territory by creating a self-conscious narrator who tells her own family story while imagining Hester’s life.

The result is a profoundly complicated novel about writing novels, especially novels without plots.

It’s hard to tell if knowledge of Hawthorne’s novel helps. Calder plays with the repressed and hypocritical world of Puritan New England as she notes contemporary problems such as children’s fixations with cell phones. In Hawthorne’s novel, Hester gives birth to a child whose father she refuses to name. For that transgression she is punished and has to wear the letter A on her dress. She and her daughter Pearl live an isolated life. The father is Arthur Dimmesdale, a minister, and he escapes public castigation but suffers from guilt. Hester’s long-lost husband, Roger Chillingworth, shows up and decides to find out Pearl’s paternity and make the man suffer.

The facts of Hawthorne’s novel are presented by Calder’s narrator, who is at home for a family reunion. Her own husband and daughter refuse to go with her, and most of the time, the narrator avoids her family and works on her novel.

Hester in Sunlight doesn’t have a lot of sunlight in either time frame, but it is loaded with references to literature (John Donne, Virginia Woolf, H.D., Jean Rhys, Edmund Spenser) and film (Demi Moore in a film version of The Scarlet Letter, Dustin Hoffman in Kramer vs. Kramer). The style of the novel is fragmented, from its numerous intentional sentence fragments to its 94 short chapters.

In the Prologue, the narrator asserts, “When Hawthorne published his book, he thought his character, a mere sliver of his psyche, would remain inside the novel’s covers. Obedient. Silent. Still. But she escaped—it can be messy—out into the sunlit imagination of readers and moviegoers.” What Hawthorne thought is speculation, but Calder is clearly taking Hester into the “light” of the writer who imagines not only herself and her family, but also Hester. It’s a sort of doubling-down on narrative complexity.

And though that has its rewards, the technique can also be frustrating; the ground constantly shifts as the narrator openly searches for a way forward (and also backward, as memory plays an important role). The narrator struggles with her presentation of Hester: “Hester can be a wide-mouthed, cow-eyed horny young woman who deserves a flogging for getting it on with a holy man. Or she can be summer dappling through plane trees onto the perambulators of starched nannies.” Or presumably many other things.

The language of the novel is fascinating, as Calder combines current objects with the imagined life of Hawthorne’s characters. For example, “[Hester] isn’t supposed to like Arthur. This is not the body to love. This weak, pale body that is as dejected as cum inside a sport sock.” Or: “Arthur sits on the rock laughing. His warm towel falling from his shoulders to shout his body at Hester, a reminder for later, when they are fucking in a cottage on the dark hairline of the forest with an album on repeat.” And as the narrator envisions the lives of the fictional characters, she also concocts her own fictional family. The layers of imaginative creativity are many.

Does the novel work? The implied audience is a small one, and even within it, some readers may find the novel more work than reward. But others will likely revel in the intricacy and admire what Calder is unflinchingly exploring in terms of invention.

*

Candace Fertile has a PhD in English literature from the University of Alberta. She teaches English at Camosun College in Victoria, writes book reviews for several Canadian publications, and is on the editorial board of Room Magazine. [Editor’s note: Candace Fertile has reviewed books by M.V. Feehan, S.C. Lalli, Rebecca Godfrey with Leslie Jamison, Ian and Will Ferguson, Shashi Bhat, Carleigh Baker, Kathryn Mockler, Lucia Frangione, Darcy Friesen Hossack, Robin Yeatman, Emi Sasagawa, Patti Flather, Peter Chapman, Janie Chang, Pauline Holdstock, Ava Bellows, Beth Kope, Geoff Inverarity, and Angélique Lalonde for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (nonfiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster