1410 Breaking, haunting, mending

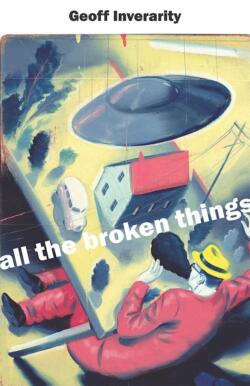

All the Broken Things

by Geoff Inverarity

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2021

$18.00 / 9781772141757

Reviewed by Candace Fertile

*

A sense of playfulness is immediately established in Geoff Inverarity’s debut poetry collection with an Author’s Preface in the form of a letter to his publisher in which he includes diary entries. The time is June and carpenter ants “crawl about, frantic, monomaniacal…. They deconstruct; they are excavators, mining wood, carving out territory; they construct, making space.” That sounds to me like the task of a poet, and in the book, the author roams about in terms of style while addressing numerous topics.

A sense of playfulness is immediately established in Geoff Inverarity’s debut poetry collection with an Author’s Preface in the form of a letter to his publisher in which he includes diary entries. The time is June and carpenter ants “crawl about, frantic, monomaniacal…. They deconstruct; they are excavators, mining wood, carving out territory; they construct, making space.” That sounds to me like the task of a poet, and in the book, the author roams about in terms of style while addressing numerous topics.

Often, the tone and diction of the poems leans to the everyday, even the chatty. And then Inverarity often shifts in tone. For example, in “At the Three Artists’ Show,” the first stanza describes a picture of old friends drinking. That sends the poem’s speaker into a memory of a man blowing huge bubbles at the Santa Monica Pier, complete with familiar dialogue: “How’s it goin’?” The final two stanzas move away from the concrete to the abstraction of writing: “In the telling of tales / even of grief and great loss / in accounts of back-breaking pain, / there is a certain joy in telling it true” and then back to the picture of friends “easing into the evening.” It works beautifully.

Repetition is one of the writer’s favoured techniques, and Inverarity deploys it effectively in several poems. In “Grief,” for example, he sets up anaphora with “Grief’s a bastard” at the beginning of the first two stanzas but then drops it in the remaining three. Retaining the pattern would have been powerful, especially since the poem is about the pain of grief and how grief is always part of a life even when it disappears for a while. Grief “suddenly doesn’t call for weeks / then comes over with too much whisky and / a bag of crappy skunkweed / just to keep you on your toes.” The concept is solid, as anyone who has experienced grief will know.

One poem in which repetition works splendidly is “For I Will Consider the Child Cyrus,” in which Inverarity includes lines from Miley Cyrus songs, complete with footnotes informing readers of the source. The poem deals with Miley as a child and as Hannah Montana, whom Inverarity’s daughter Imogen watches on television. And to top off the inventiveness of this poem, the form is reminiscent of Christopher Smart’s “Jubilate Agno,” in particular the section “My Cat Jeoffry.” Smart’s eighteenth-century free verse poem (ahead of its time) uses anaphora and other forms of repetition to create a prayer-like chant, fitting for Inverarity’s poem about a singer and song lyrics.

Occasionally Inverarity uses font size to develop a poem, and it can come off as a gimmick. In “Hard Living,” the words “equilibrium” and “morphs” are enlarged and bolded as titles for sections of the poem. I suppose the effect is to unbalance the poem to reflect the difficulty the speaker is experiencing. As he says at the beginning of this piece, “it’s hard living on an island, especially when your molecular / structure’s as unstable as mine is” and the jittery construction may appeal, but the repetition of a bad joke is tedious, and the ending of the poem with the first line repeated and subsequently diminished by a word in each following line (and then by a letter) doesn’t quite work.

Oddly for a collection of poetry, the most powerful selection is what many would call a prose poem or maybe even prose. “My Mother’s Haunting” is a wrenching piece about the care a woman took in keeping her house clean and organized, so that even after her sudden death, her son arrives at her home in Scotland to find carefully wrapped and labelled spare bedding. She also saved and reused plastic containers and lids and knitted squares from leftover wool and made them into blankets to wrap, label, and donate. This piece is a sign of a son’s appreciation and love for his mother, a woman who survived the Second World War and did what she could to be prepared “for the cataclysm, the earthquake, the explosion, the flood or famine, the sound of the air raid sirens, the thunder of invisible bombers, cancer, a stroke, or perhaps even the discovery that there is another woman in your husband’s life.” Whatever you label it, “My Mother’s Haunting” will haunt. Its rhythm and flow, its intensity of sound and emotion — these are the hallmarks of winning writing for me, in poetry or prose.

Most of the poems in the collection are short, but Inverarity does have a long sequence titled Mars Variations that is comprised of 29 short poems. He introduces the section and says, “As an atypical fractal narrative, these poems could be read in any order, shuffled like cards — but the constraints of existence and physical production mean they have to be presented here as a linear ‘sequence.’” That explanation didn’t help me. The poems have a collision of topics: a Mars (and horror movies), Guy Fawkes, the Wicker Man, and Cromwell.

The book ends with an Author’s Epilogue, a poem of hope that “all the broken things will be mended,” and I fervently wish that will happen. However, right now, given events in Ukraine, it just looks like more and more things are being broken. But we have poetry to help, and while I had some struggles with this book, Inverarity offers much of value for readers amenable to a writer experimenting with his voice.

*

Candace Fertile has a PhD in English literature from the University of Alberta. She teaches English at Camosun College in Victoria, writes book reviews for several Canadian publications, and is on the editorial board of Room Magazine. Editor’s note: Candace Fertile has recently reviewed books by Angélique Lalonde, Jane Munro, Arleen Paré, Ian Williams, Amber Dawn, Rachel Rose, and Susan Alexander.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

9 comments on “1410 Breaking, haunting, mending”