1737 The sky’s the limit

Why Humans Build Up: The Rise of Towers, Temples and Skyscrapers

by Gregor Craigie, illustrated by Kathleen Fu

Victoria: Orca Book Publishers, 2022

$29.95 / 9781459821880

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

*

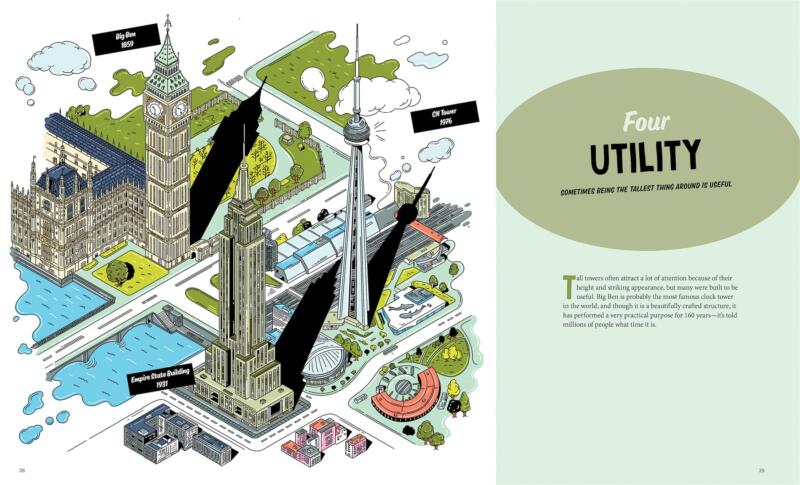

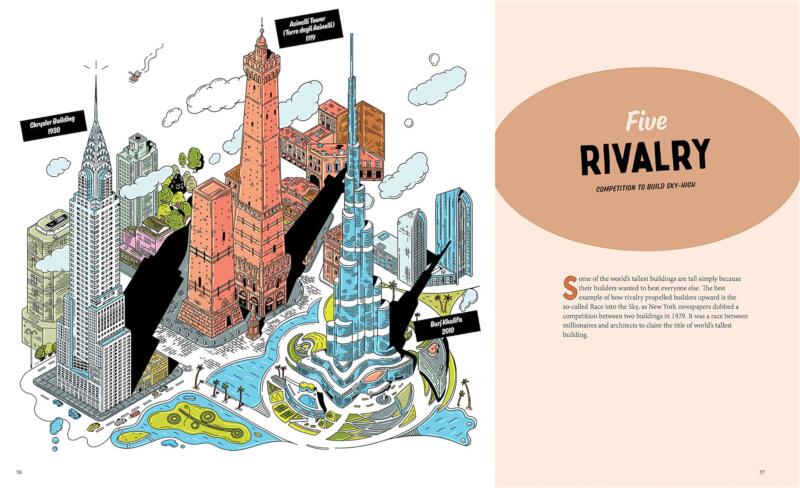

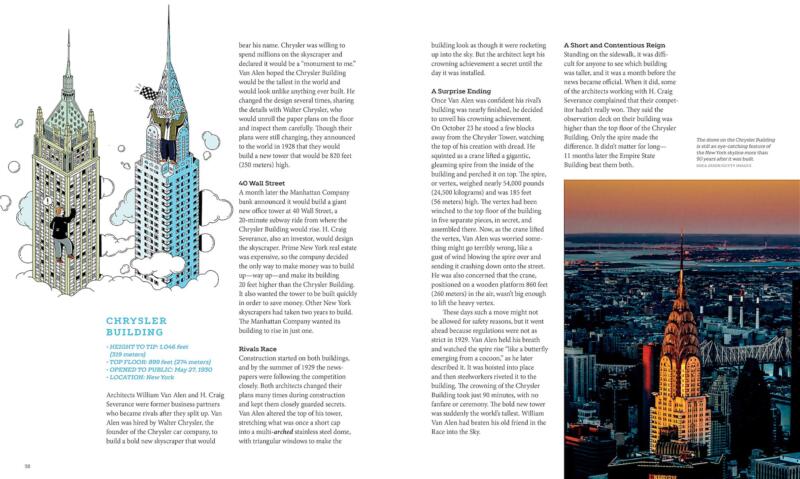

Was the Tower of Jericho built as a defensive watchtower or a mechanism to help farmers calculate the summer solstice? What are the advantages of continuous concrete pour? Who was the Ben after whom Big Ben is nicknamed? (Its true name is the Elizabeth Tower). In the competition for tallest building, who makes the decisions, and how? Why is Bologna’s Garisenda Tower shorter today than it was in the 13th century? Who is Malika Walele, and why don’t we know more about her? Novices to architectural studies — whether the “juveniles” at whom the book is aimed or elders such as your reviewer — will learn much about these and other questions in this appealingly laid-out, thematically organized overview of tall built structures throughout history.

Was the Tower of Jericho built as a defensive watchtower or a mechanism to help farmers calculate the summer solstice? What are the advantages of continuous concrete pour? Who was the Ben after whom Big Ben is nicknamed? (Its true name is the Elizabeth Tower). In the competition for tallest building, who makes the decisions, and how? Why is Bologna’s Garisenda Tower shorter today than it was in the 13th century? Who is Malika Walele, and why don’t we know more about her? Novices to architectural studies — whether the “juveniles” at whom the book is aimed or elders such as your reviewer — will learn much about these and other questions in this appealingly laid-out, thematically organized overview of tall built structures throughout history.

At first blush, a chronological approach — from the Tower of Jericho (circa 8300 BCE) to Central Park Tower (finished in 2021) — might suggest itself. However, Victoria writer, journalist and CBC radio host Gregor Craigie and Toronto illustrator and architecture graduate Kathleen Fu successfully eschew straightforward chronology for these buildings’ purposes — which range from security to spirituality, from efficiency to security.

Abundant photographs and, more significantly, Fu’s intricate and evocative renderings (she describes her style as “Where’s Waldo-esque”) neatly link the structures within each theme. The ingenuity behind the Home Insurance Building, The Eiffel Tower, and the Flatiron Building, for example, is reinforced by their placement on a single page amidst a bustling street scene and geographical features such as trees and water.

The writing style of Why Humans Build Up engages. Craigie’s introduction — a personal narrative — both informs readers of the book’s genesis and prepares us for its structure. As a 5-year old, he was captivated by the ten-year old Calgary Tower, which evoked “how” questions about its height and construction. Decades later, his own son’s “why?” caused Craigie to see his interest from a broader perspective. This anecdote sets us up for details such as dimensions, process, history, background, and materials; it is also likely to resonate with young readers, who may relate with their own initiation story. Although the tone in the subsequent 10 chapters is less intimate, the prose remains accessible and straightforward. Perhaps the work would have benefitted from a conclusion that circled back to the winning introduction and summarized.

Craigie and Fu are both macrocosmic and microcosmic in coverage. Their survey spans the globe, with countries such as Chile, Japan, Hong King, Moscow, Korea, Bahrain, Egypt, France, the UK, and the USA represented. To this reader, the fairly plentiful Canadian coverage was a welcome surprise. Lesser lights like the Sudbury Trace Superstack, UBC’s Tallwood House, and Manitoba Hydro Place join the expected CN and Calgary Towers. To their credit, Craigie and Fu devote a page to the “towering totems” of British Columbia, informing young readers that the tallest totem in the world is on the traditional territory of the Kwakwaka’wakw, and that totems were at once banned by settler governments and stolen by museums and collectors. Interestingly, at the time of writing, the return of a totem by the Royal BC Museum to the Nuxalk nation made provincial headlines. The range and variety of structures discussed go well beyond the garden variety.

While clearly enamoured of his subject, Craigie is not an unabashed booster. He sheds some light on the underbelly of architecture, citing, for example, the controversy around luxury towers amidst the favelas of São Paolo, the cramped “coffin homes” of Toyko, and the tragic 2017 fire in London, England’s Grenfell Tower, a social housing complex. I could not help but think of another “who” question: Who were the workers who actually toiled on the construction of these edifices? The deaths of migrant workers on Dubai’s Burj Khalifa came to mind as a recent and salient example.

Gregor Craigie and Kathleen Fu cover considerable territory in the space of under 100 pages — including a useful glossary, a list of resources, and a nod to women in architecture, including Walele, who was part of a team of women responsible for the Leonardo in Johannesburg — Africa’s tallest building. Some other questions in my introduction are not given easy, quick answers. While the book enlightens novices about a myriad of architectural questions, it doesn’t seem to oversimplify; it succeeds in conveying the mysteries and complexities of the construction of tall structures. Why Humans Build Up: The Rise of Towers, Temples and Skyscrapers is a fitting initiation into architecture in its many forms. Young — and older — readers will also learn about history, material culture, and sustainability along the way.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is Professor Emerita at Thompson Rivers University. Her scholarly publications (co-authored and edited and co-edited books and numerous peer-reviewed articles) have focused on Canadian fiction, theatre, small cities, third-age learning, and the scholarship of teaching and learning. In addition to counteracting ageism by maintaining a growth mindset through freelance writing and community engagement, she promotes later-life learning through her involvement as a board member, coordinator, and instructor for the Kamloops Adult Learners Society. Her upcoming KALS course, “Canadian Short Fiction: National Literature and Serving the Story,” brings together work by Mavis Gallant, Miriam Toews, and Maria Reva. Editor’s note: Ginny Ratsoy has recently reviewed books by Cynthia Flood, Reed Stirling, Maria Tippett, Gillian Ranson, Jo Owens, and Iona Whishaw for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1737 The sky’s the limit”