1594 The celebrated camera obscura

Art, Research, Play: The Midnight Sun Camera Obscura Project

by Donald Lawrence, Josephine Mills, and Emily Dundas Oke (editors), foreword by W.F. (Will) Garrett-Petts

Lethbridge: University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, 2021

$39.95 / 9781927770115

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

“This is a book that arrests attention but won’t stand still.”

“This is a book that arrests attention but won’t stand still.”

Thanks to W.F. Garrett-Petts for this assertion in his foreword. Professor and Associate Vice-President at Thompson Rivers University, and a frequent collaborator with Donald Lawrence on projects related to art and community, he has – I feel – given me permission to discuss this book as it strikes me, with astonishment and insight, with enchantment and bewilderment, as at once a thing of beauty, a learning experience and an adventure, or, as the subtitle has it, “Art, Research, Play.”

The Midnight Sun Cameras Obscura Project (MSCO) brought together an “international group of artists and scholars interested in camera obscura [literally “dark room”] and related optical phenomena as a meeting place of art and science, cultural and wilderness settings, learning and play” to indulge in a range of public site installations around Dawson City, offering exhibitions, workshops, performances, tours, talks and various entries to artistic, scientific and philosophical inquiries into optical phenomena. The venue was the Land of the Midnight Sun, the time the Summer Solstice, the optimal time and place for working with light.

Donald Lawrence, the principal investigator, inspiration and project leader for MSCO and Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art at TRU has crossed my path a number of times over the years. There is always something to do with a pinhole camera (the simplest possible camera with no lens, just a pinhole-size opening to focus light rays within a small area to produce an inverted image), often strapped to the side of his kayak. Then came the camera obscura (“a darkened space into which light is admitted through a small aperture, sometimes aided by a lens and sometimes a mirror also, with an inverted image of the surrounding view cast by the light onto a surface inside”). Some projects involved floating lighthouses towed by kayak in the Salish Sea around the Gulf Islands, Vancouver, and Victoria; a 1960s German folding Klepper kayak converted into a floating camera obscura, and featured in a video Ten Days On the Island created for Tasmania’s biennale; and a “One-eyed Folly” on Lake Nipissing in north-central Ontario. In each case, Lawrence planned his marvels in notebooks which he filled with meticulous drawings & diagrams.

During the years leading up to the MSCO Project, he knocked on the doors of international scholars in the histories of art, science and philosophy. They compared research on Kepler, the Enlightenment, the optical metaphors of Shakespeare, the theories of Descartes and how the camera obscura played a decisive role in the rise of medicine, and the connection between Spinoza and David Hockney, among other topics. He visited optical instruments in ancient universities and small private museums, and “found close companions in Europe for his special brand of philosophy and art.” They speculated about points of intersection in the thought of Greek, Arabic and Chinese scholars: Aristotle, Ibn a-Haytham, and Shen Kua. In his essay in this book, “The Camera Obscura in the Mirror of Myth,” the Netherlands philosopher Petran Kockelkoren wonders whether the Cartesian worldview of inner vs outer worlds may be “a typical western construct with limited applicability elsewhere on the globe.”

So many questions. What happens when we look at art? What are the relationships between physical optics and neurological connections? How do physics, aesthetics and physiology relate to each other?

This is serious stuff, and much of it is explored in this book as it documents the work of the scholars and artists who followed Lawrence to the Yukon. The project evolved in stages over a period of years. beginning in 2004 when he exhibited his Pinhole Photography Project in Dawson City’s ODD Gallery (so named for its location in the former Odd Fellows Hall). He and likeminded artists, community members and wilderness enthusiasts gathered at Bombay Peggy’s, “the social hub of Dawson City,” to imagine a festival of cameras obscura. The notion simmered. Then in 2010 it re-emerged. By 2013 funding was obtained from SSHRC’s insight program, with the Klondike Institute of Art and Culture as the lead partner organisation. In 2014, this select group of artists, curators and scholars made a preparatory expedition to the Yukon, preparatory workshops followed, and the MSCO Festival was realised a year later at the 2015 solstice. It is enjoying an afterlife at various venues, inside and outside museums. This book is part of the on-going process.

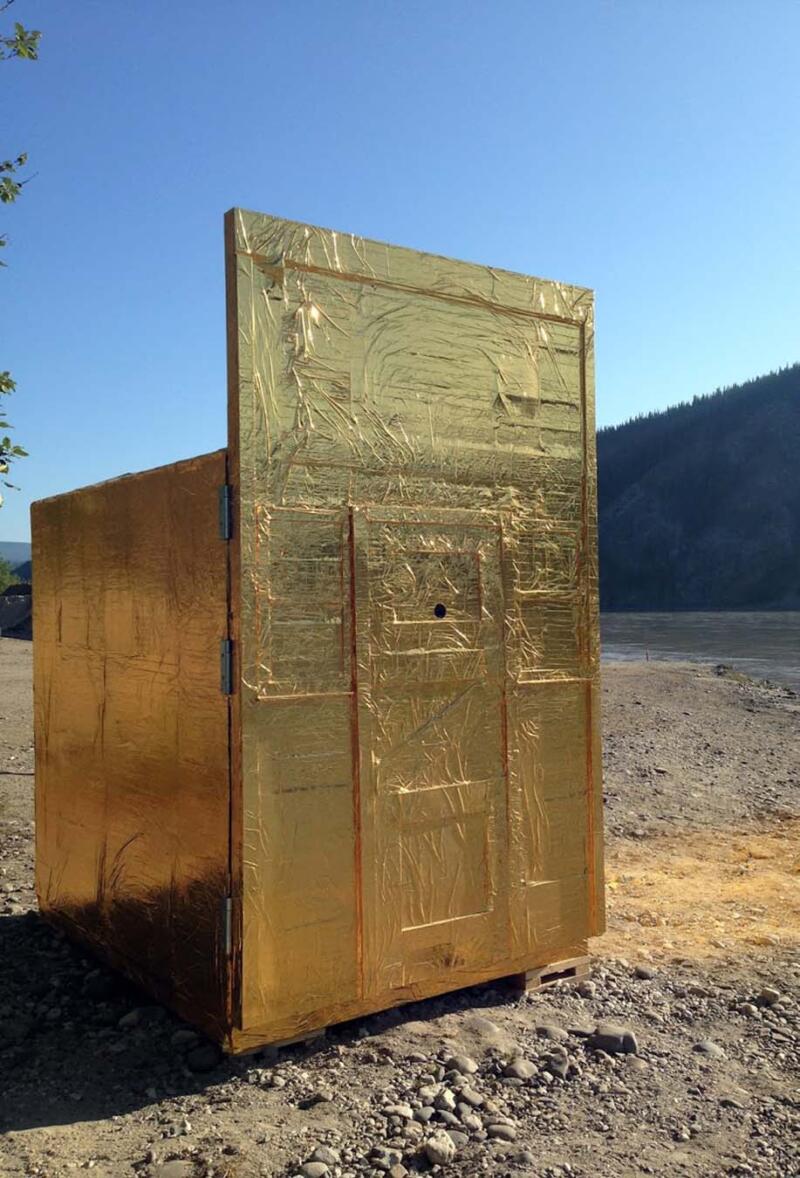

Let’s start with the cover. Holly Ward and Kevin Schmidt collaborated on this work, Eye of the Beholder, described by Josephine Mills in her essay “On Art and Research” as “a gold nugget the size of a golf cart.” The two interdisciplinary artists have impressive international CVs not readily summarized. Ward “seeks to develop artistic engagements with non-human entities and ecological systems in a future-oriented practice.” Schmidt’s work in various media “functions as a critical and subjective examination of spectacle, looking at intersections between DIY culture and contemporary art production.” In other words, they can do anything and are interested in everything, and are ideally qualified for participation in the MSCO Project.

After opening the cover, we wend our way through several black blank pages and a journey of four double-page photographic spreads leading to a frontispiece depicting a person lying on their back on a mattress with their head inside a ramshackle box, which is not really ramshackle but a camera obscura in use. Only then do we arrive at the title page with information about writers, editors and publisher, and proceed further to contents of book and Festival and guides to events, works and artists — en route floating through an upside-down image of the river, an image which we realise the camera obscura will turn upright for us. We have been lured into active involvement in the MSCO Project, as we turn the pages of a book which, as Garrett-Petts warned “won’t stand still.”

Eye of the Beholder turns out to be twins — one camera obscura on the slopes of Moosehide Slide, and the other in the valley of the Klondike River, north of its confluence with the Yukon. Donald Lawrence explains in “Camera Obscura in Dawson City, Yukon,” his discussion of the various artists and their projects: “it is gravel, not gold, that is the Klondike Valley’s most salient feature,” and the one which Schmidt and Ward set out to foreground. The slide and deforestation occurred about seven hundred years ago; investigation is concerned with human intervention and resource extraction, compared with environmental processes occurring over time.

Characteristically, Lawrence is reminded of a polygon in a 16th century engraving by Durer, an image shown opposite a photo of Ward and Schmidt engaged in on-site assembly. As their contribution to the gallery exhibition they used their structures as actual photographic cameras, exposing photographic papers inside the “Eyes” and processing them then and there into images which Lawrence finds “reminiscent of circular Kodak photographs of the late nineteenth century.” Immediately following Lawrence’s essay, Eye of the Beholder appears in a series: a double-page panorama with gravel, river and trees at the site of a nineteenth century dredge from Gold Rush days; a full-page close up of the structure, another of the view from inside, several small photos of the work-in-progress and the placing of its base; concluding with a double-page panorama of the site near the Moosehide Slide.

Eye of the Beholder, with a background of the town and river, appears again opposite the essay “The Camera Obscura on the Move: Body, Animation, Imagination” by Sven Dupré of Utrecht University and the University of Amsterdam, who comments on how the twin “eyes” were “made to resemble the form, colour and glimmering effect of pyrite, or fool’s gold, and on their outside surfaces reflect the surrounding soils and stones while producing another optical map of the hills and landscape inside the ‘pyrite’ camera obscura.” Later, during Josephine Mills’s essay “On Art and Research” (in which she discusses manoeuvring the intricacies of SSHRC and other funding bodies), the Eyes are glimpsed in the distance from the far side of the river, and a few pages later we see someone climbing inside one. Mills goes on to curate an exhibition at the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, where both “Eyes” are accompanied by notes and instructions for the viewer.

The object which appeared a small if slightly intrusive detail in the northern landscape becomes inside an exhibition gallery a presence dominant and serene, like something from The Day the Earth Stood Still. In the exhibits — at Lethbridge, Kamloops and McMaster to date — Eye of the Beholder and the other creations of the MSCO Project bring together pieces formerly scattered about a landscape, their discoveries and experiences, some reconstructed to simulate the original, others in models and photographs, while others such as the photo taken inside “Eye” are real products of the original.

The research has been transported and replicated, and now, with the appearance of this book, duly published. The volume we hold in our hands is part of the research project. We are invited to make what we will of it, artistically, philosophically, scientifically, to immerse in the experience, to pry, to tinker, and to experiment. The book won’t stand still.

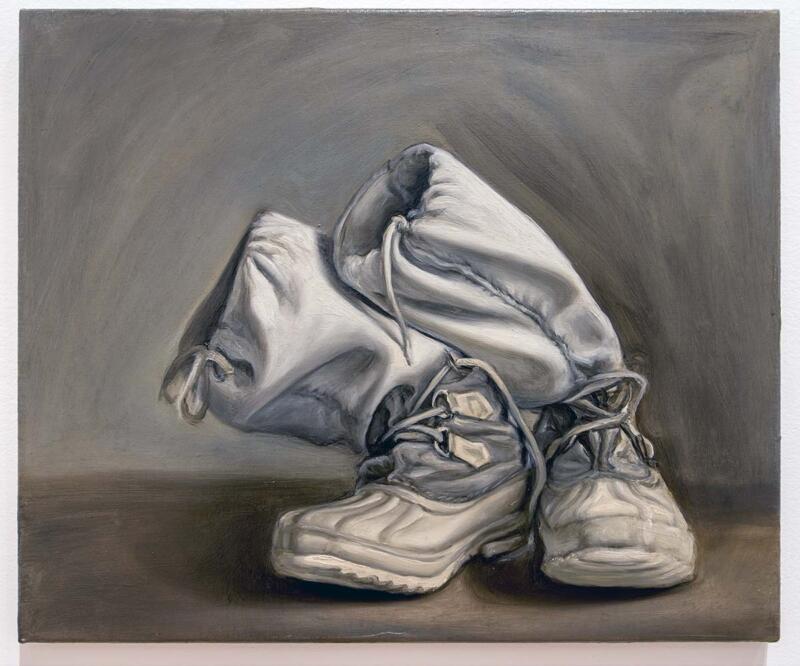

And I have looked at only one of the projects within the Project. I could devote as much space to Carsten Wirth, who brought his interest in light and art history from his Berlin studio, transforming a camera obscura image of a pair of snow boots into a painting worthy of Andrew Wyeth. In this effort to show that the visitor’s experience with arts is also research, he invited “the public to join the artist in exploring how we see and create imagery with light”.

Or I might follow Andrew Wright, as he walks about Dawson City, carrying a large mirror, exploring reflections and photographic reversals, and relating observations under the Midnight Sun with experiences at the Greenwich Royal Observatory … stepping through Alice’s Looking Glass.

Or I might marvel as Dianne Bos makes stars visible within the darkness of her Camera Obscura, even though outside they are invisible in the light of the Summer Solstice, into the darkness within, linking her darkness visible to experiments with light and time in fifteenth century cathedrals.

Or I might be a tourist inside the Vanscura, an ordinary van adapted by Mike Yuhasz of Dawson’s Odd Gallery. Inside the moving vehicle, I could watch a screen showing images of the passing landscape while an audiotrack read from Nietzsche, Goethe and Jack London.

Or I could visit Doug Smarch, Jr of the Tlingit nation as he explores the importance of Tlingit trading networks and their relationships to the impact of the Klondike Gold Rush, using the most recent optical projection equipment, contemporary digital culture and traditional graphic imagery.

Or, leaning on my cane, I might encounter Ernie Kroeger, whose photographic art is represented in such public collection as the Canada Council Art Bank, the Art Gallery of Alberta, the National Gallery of Canada and the Museo Nazionale della Montagna in Turin, Italy, at the intersection of art-making and walking and perceive the walking stick as a perceptual tool.

There’s more, much more than can receive even passing mention here.

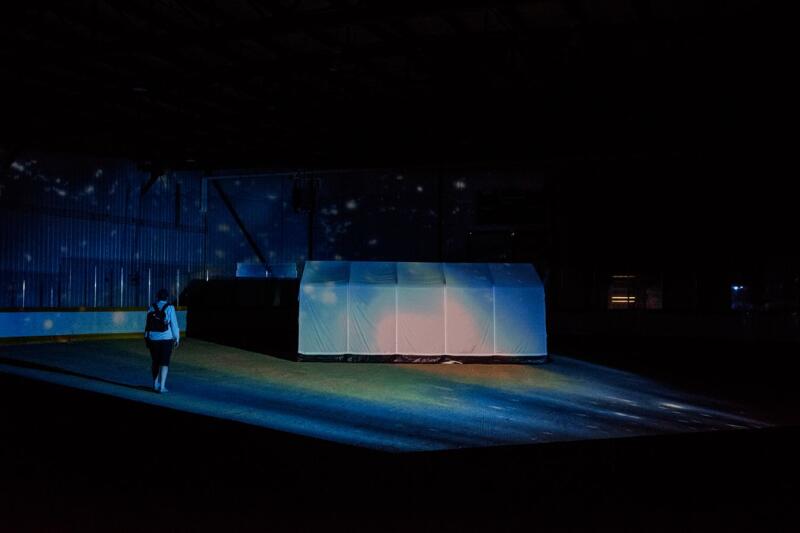

As always, I am intrigued by Donald Lawrence’s own works, for instance the Pavilion Camera Obscura, by the ferry dock (“a large structure bolted, turnbuckled and built of posts and beams, which held a raised platform and extended into the air holding raw canvas sails”), part of the Sternwheeler Camera Obscura Workshop. Later, after the Dawson Festival, moving south to Nanton, Alberta, he transformed an abandoned grain bin into the World’s Most Corrugated Camera Obscura, a sculptural object cobbled together from wrecks and junk from antique shops, saturating geography and art history with current technology, culminating in surprise and delight.

Louise Barrett titles her essay of Lawrence’s work “Poking and Prying with Purpose; the working art of Donald Lawrence” Could “Poking and Prying with Purpose” be a definition of science? How do patterns of light work with found images and objects? What possibilities hide in a reel of forgotten 16 mm film?

In what ways do the false fronts of Gold Rush streets resemble the fanciful architectural follies of eighteenth century English gardens? How does myth figure: does something in Dawson City relate to Zeus on Mt Ida on the island of Crete?

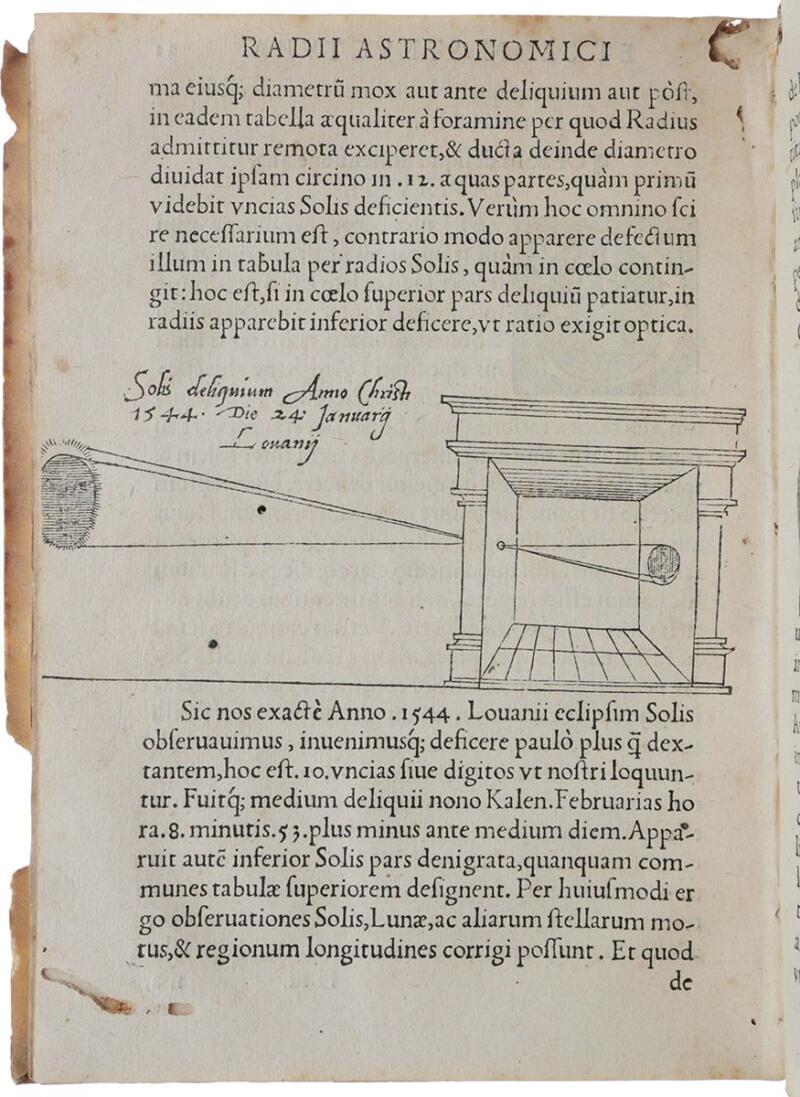

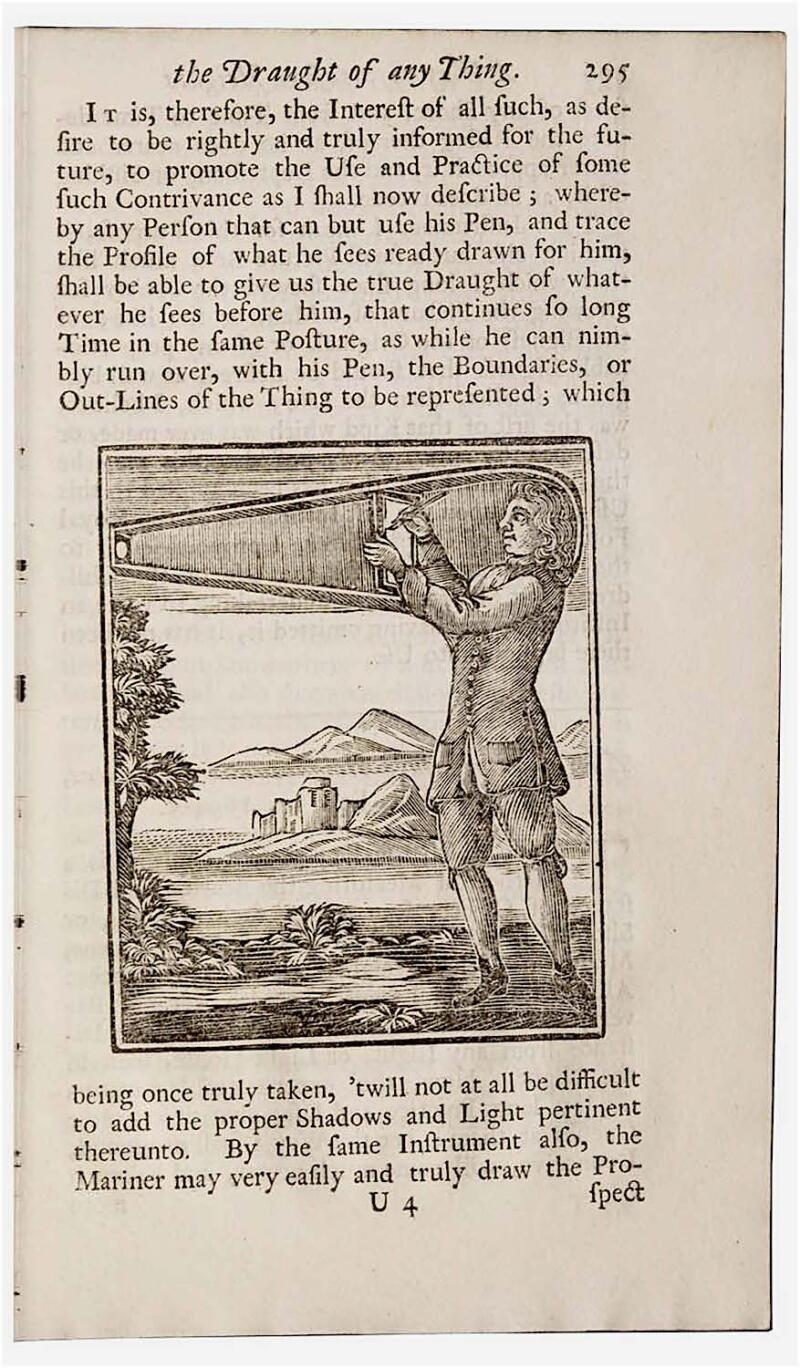

A portable camera Obscura designed to fit on people’s heads reminds me of the video games headgear recently sported by younger members of my family, but then it turns out this sort of “picture box” was shown to the Royal Society in 1694. I think the View Masters, kaleidoscopes. and 3D glasses of my youth belong in this history of “embodied viewing.”

At the meeting place of wilderness and cultures, travelling by canoe with a nineteenth-century camera lucida clamped to a paddle, Lawrence and his colleagues challenge common perceptions of boundaries between learning and play. This is “a responsive interplay of experimental practice and public engagement, with informed scholarship as a guiding objective.”

If you have read this far, you realise this book is not easy to review. There is a lot going on. The art, research and play involve seventeen artists and six contributors of text, and twenty-three points of view, with some inevitable repetition as differing approaches share a context. Struggling to meet demands of the “audit culture” part of grant applications, Josephine Mills points out that there is literally nothing new under the Midnight Sun, that a similar method of group demonstrations was employed by the European court salons from the 16th through the 18th centuries, that art as research is old idea dating from long before the Enlightenment insistence of scholarly specialisation and that by the mid-eighteenth century, the camera obscura was standard equipment on scientific expeditions.

The research involved in the MSCO Project, including a few failed experiments, moves to “the art gallery as a behavioural setting and a social experience,” each stage a replication but also an on-going engagement of artist and observer. As Mills writes, “The research involved with art tears through assumptions and opens new ways of seeing the world and our connections within it.”

Contributors include scholars and artists with international reputations, graduate students engaged as part of the research team, and one second-year visual arts student. Perhaps not surprisingly, the undergraduate, Levi Glass, is the team member most distressed when a project goes wrong, but he soon finds that the failure “led to a greater discussion on the spirit of play and the inherent risk of failure, particularly with highly technological or complex projects,” and learns that blunders become opportunities, and “failure and success evolve in tandem and are divided by a thread.”

Besides Lawrence, the editors are Josephine Mills, director and curator at the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, and Emily Dundas Oke, researcher and emerging curator. The whole roster of players is: Louise Barrett, Dianne Bos, Lea Bucknell, Patrice Coté, Emily Dundas Oke, Sven Dupré, Levi Glass, Bob Jickling, Petran Kockelkoren, Ernie Kroeger, Donald Lawrence, Josephine Mills, Doug Smarch Jr., Holly Ward and Kevin Schmidt, Carsten Wirth, Andrew Wright and Mike Yuhasz.

And what were they doing? Mills poses a problem:

Both academic and popular conceptions of research have narrowly focused only on the thinking part of research — what theorists and scientists do. And the problem is not just a debate about whether or not art fits within the folds of research: fighting over funding, status and disciplinary boundaries has led to a far too restrictive idea for all scientists and scholars about what research is and what research does.

She then answers her own problem: “The research involved with art tears through assumptions and opens new ways of seeing the world and our connections within it. Making and engaging with art creates possibilities for bumping us out of the ruts we have dug through routine, stopping to look — really look — at the everyday phenomena we encounter, and prompting reflection and discussion.” In other words: Art, Research, Play.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve writes about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. She co-founded the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina on Gabriola Island. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has recently reviewed books by Iain Lawrence, Lisa Anne Smith, Mowafa Said Househ, Eric Schmaltz & Christopher Doody, Carolyn Daley, and Roy Innes.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1594 The celebrated camera obscura”