1434 Kootenay mother lode

Silver Rush: British Columbia’s Silvery Slocan, 1891-1900

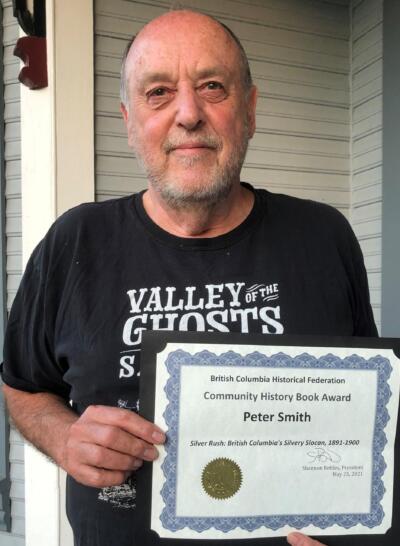

by Peter J. Smith

Ladysmith: Two Daughters Publications, 2020. Also available at many BC bookstores.

$39.95 / 9781999045906

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Kootenay Mother Lode: Mammoth Tome offers Detailed Account of Mining History in BC’s Colourful Slocan District

Kootenay Mother Lode: Mammoth Tome offers Detailed Account of Mining History in BC’s Colourful Slocan District

A book the size of the old Eaton’s Catalogue arrived recently and I hoisted it onto my lap as excited to crack its covers as a kid at Christmas on the hunt for a Montreal Canadiens hockey sweater. I soon learned I’d need my historian’s prospecting pick to mine this compendium of everything anyone ever wanted to know about the heyday of silver mining in British Columbia’s Slocan district. I was game.

Author Peter J. Smith has given us a book that one commentator has called “magisterial” and others have praised for the “mass of information” he has compiled. No argument here. This short nine-year history is crammed with every conceivable detail of an era of discovery, rivalry and jealousy.

At more than 600 pages in an over-sized format with an unconventionally long column length, the historian’s job is akin to looking for the elusive veins of an underground mine. The picking requires time and patience. And yet there are many rewards in those pages.

Smith has been so exacting in his research that in the first chapter alone I encountered at least 30 names and nicknames of individual silver seekers. A selection: Black Jack Cockle, Stepladder Brown, Lemonade Dan, Porcupine Billy, Yellow Dog Smith, Whorehouse Bob, Toughnut Jack Clunan. And on it went.

There was also a stunning array of colourful claim names: Noble Five, Payne, Blue Bird, Side Issue, Last Chance, Lucky Number and Lady Jane, the list seems endless and Smith does his best to capture a large portion of them. Discoveries on Toad Mountain near Nelson brought many more claims and made Nelson a flourishing regional centre.

Women also make appearances. Fool Hen Anderson was an early claim-staker. So was Mrs. E.M. Pound. But many others came to relieve prospectors of their precious metals inside the many hotels that seemed to rise overnight and burn to the ground just as quickly.

Dance hall girls won lonely prospectors’ hearts at entertainment centres like Kaslo’s Comique, that “notorious palace of sin.” But there were plenty of preachers around to offer the gospel and absolution on Sunday before the business of staying alive began again on Monday. Missing from the list of Kootenay clergy was one Rev. Henry Irwin, the sainted Father Pat that served the Trail-Rossland mining and smelting communities. Like the others listed, he had his hands full.

Smith is a good storyteller, holding reader interest with the novelist’s talent of making you turn the page. He also peppers his narrative with many famous names. Some of them are writers like Mark Twain, Charles Dickens and Jack London. On the political front, Louis Riel gets a mention. So does Teddy Roosevelt. Slocan’s “Fabian socialist,” Dora Kerr and her husband R.B. Kerr are noted.

If they didn’t get to the Slocan in person, some, like Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and Calamity Jane were discussed from a distance with loose connections to the silver mining era in nearby Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. Unknown prospectors might be remembered in short clips of pioneer poetry. The better known poets, giants such as Walt Whitman and Rudyard Kipling, were cited. Odd for a mining book, Robert Service, the Bard of the Yukon, does not merit a spot in the index, but George Bernard Shaw does.

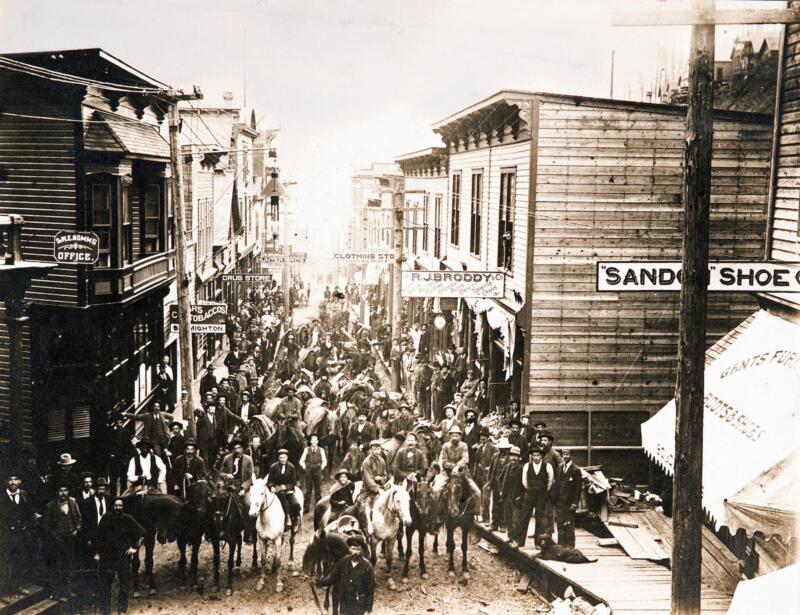

Smith situates Silver Rush in a North American context. The world came to the Slocan in 1891 and kept coming after the great Chicago world’s fair of 1893. But it also faced the downturn of that year’s “Great Panic.” It was among the early disasters to be endured. Others were to follow, particularly involving fires that consumed several towns.

Johnny Harris, the so-called king of Sandon and master of the Reco mine, was able to ride such ups and downs, playing a prominent role in this history. Like many others, he was an American who saw his fortune buried in the Slocan. Always a superstitious hustler, with his lucky rabbit’s foot to hand, he stayed from boom to bust and back again . . . and got rich.

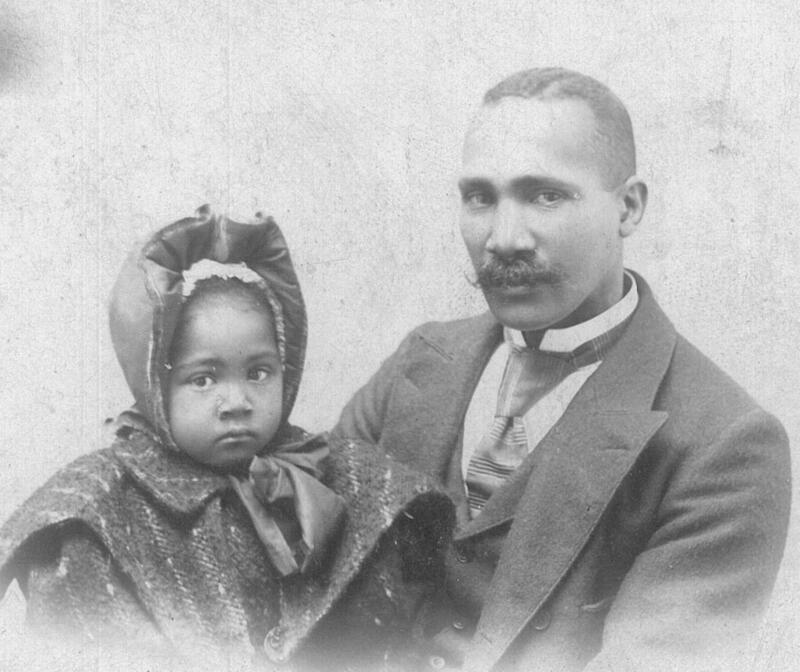

As Smith points out, more Americans migrated here initially than any other nationality and the British-American rivalry grew in significance. He also accounts for the Asian, Italian, eastern European and Anglo-Saxon immigrants. As with many North American mining communities of the period, the Asian migrants were the most harshly treated by a largely nativist population. Much later, during the Second World War, a Japanese internment camp was located at New Denver.

Claim seekers E.C. (Eric) Carpenter and Jack Seaton were also early participants who made good in the mountainous, often snow-laden region. They set up shop at places called Eldorado City, Eagle City and Beaver Lake City, names that later changed or disappeared altogether. Eldorado City, for example, became New Denver.

Several entrepreneurs also played significant roles in opening up the Slocan, men like Nelson’s Fred Hume, E.C. Coy, and Jim Wardner to name three. Some of them were bondsmen, investors who held bonds on property that might yield returns. Others became developers, suppliers and justices of the peace as the area boomed.

Silver Rush could serve as a textbook on regional mining history, replete with technical explanations, and a thesaurus of the lives of the many men (and some women) who moiled for Slocan silver. Smith has done his homework with regard to the scores of individuals that populate the book. Even the passing mention of seemingly obscure figures is accompanied by a short biography.

Of the many issues of the day, bimetallism, is centred out for special attention. The battle for a dual currency standard, recognizing silver as well as gold, was a central issue during the 1896 American election. Democrat William Jennings Bryan, the “darling of the Slocan miners,” championed bimetallism and lost to William McKinley.

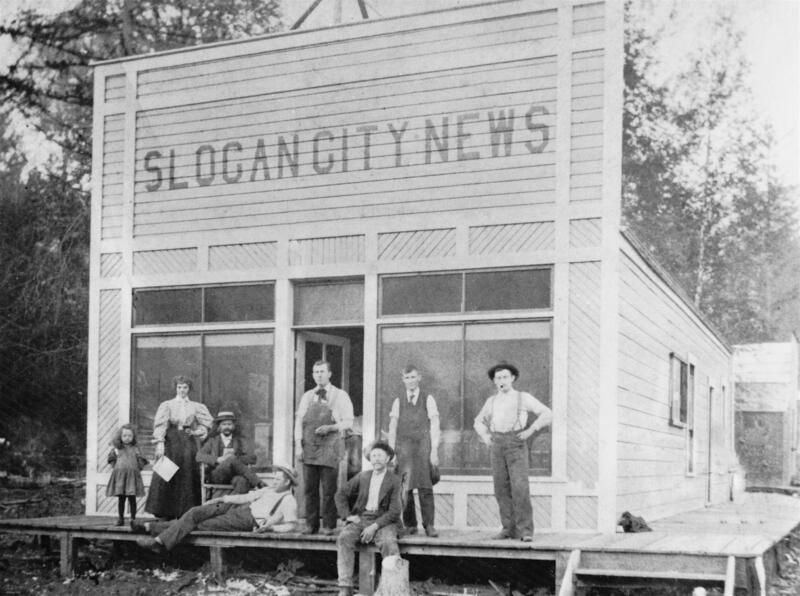

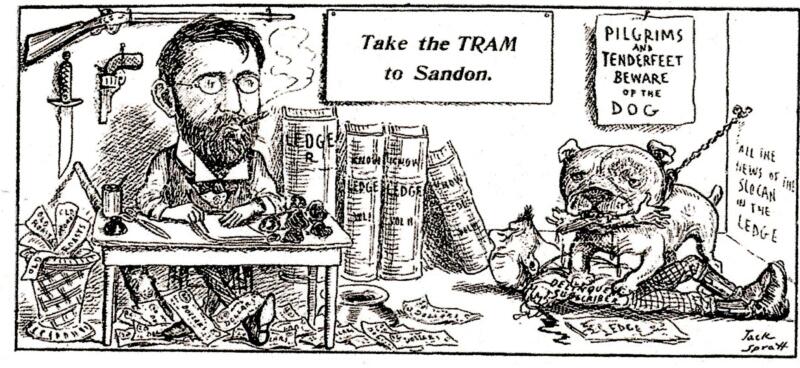

A critical source for all historians are local newspapers and Smith has done excellent archival spadework to expose us to the journalistic world of the Slocan. Colonel Robert T. Lowery of the New Denver Ledge, David Bogle of the Rossland Miner, and John Houston of the Nelson Tribune stand out. As Smith notes, “The local newspapers played an important role by maintaining a positive outlook, promoting Slocan interests and doing their best to entertain and inspire their readers.”

When they weren’t providing sassy accounts of murders, claim jumping and the exploits of the ever-hopeful tenderfoot, they were constantly wooing the local business community to help sustain publication with advertising. These are the historian’s saviours and Smith gives them their due.

In a rugged untamed region like the Kootenays, papers like the Kaslo Kootenaian, Slocan Pioneer and Sandon Paystreak offered readers an unburnished view of the villains, winners, losers and hookers who formed the communities of the area. The editors also relished sarcastic exchanges about each other in their pages. The competition could be fast and furious, especially when the stakes involved real estate, an income-supplementing sideline for many a country editor, including the redoubtable John Houston.

Missing from the collection, for some reason, is the Trail Creek News, the weekly started in 1895 to serve the smelter community not far from the Slocan where much of the ore would go for refining. Not missing, to Smith’s credit, are accounts of the women who worked in the newspaper trade, including Margaret O’Rourke and Mary Van Buren of the Kaslo-Slocan Examiner.

Also here in abundance are the social and cultural institutions that attracted the “boomers, dreamers, schemers and followers” who came and went from the region. The Kaslo Comique, in particular, became a venue for vaudeville and other entertainments. Of course, preachers to the region looked askance at what was going on at the Comique, perhaps preferring the gentler sounds of a concert by the brass band in New Denver.

Railway baron rivalries brought a mishmash of tracks to the region to transport men and women to the silver rush and haul out the ore they would uncover. The trains were assisted by a fleet of sternwheelers that brought grubstakers, land-grabbers and mine speculators as well the “soiled doves” that would work the street below the “dead line” of Sandon’s celebrated Reco Avenue.

The book also gives us glimpses of the local police officers who were on hand to maintain the peace at the numerous lively brothels as well as to watch over towns given to heavy drinking, the faro table and the occasional shootout at the local saloon.

Photographs and maps provide welcome breaks from the sometimes-dense text and Smith is to be credited for painstakingly retrieving the pictorial depictions of remote camps, business establishments, hospitals, churches, banks, post offices and schools. Footnoting is relentless, another boon for the historian. However, the index seems limited to people’s names. Place names and pertinent issues also would have been helpful.

Smith, a former civil servant who once worked a claim in the region, is not the first to travel this historical route, but his book is possibly the most exhaustive. Silver Rush is a full portrait of the people and the towns that were destined to make history and ultimately become ghosts of the past. We are richer for it.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker. His work has appeared in The British Columbia Review since it was founded in 2016 as The Ormsby Review. Editor’s note: Ron’s book Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for Its Life in Wartime Western Canada, new from University of Toronto Press, is reviewed here by Bryan D. Palmer. See also here for Ron’s essay on trade unionist Harvey Murphy and here for a review by Mike Sasges of Ron’s Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb. Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Chad Reimer, Robin Winks, Tom Wishart, Janice Baker, & Lynn Campbell, Gregory Betts, Maureen Webb, and David Lester. He lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1434 Kootenay mother lode”