1269 A choice Kootenay collection

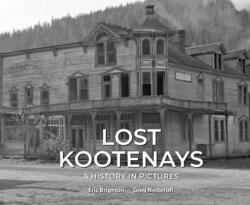

Lost Kootenays: A History in Pictures

by Greg Nesteroff and Eric Brighton

Lunenburg, NS: MacIntyre Purcell Publishing, 2021

$29.95 / 9781772761641

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

Editor’s note: the full photo captions below are taken directly from Lost Kootenays.

*

Kootenay Home: A prize collection of historic images shares the Kootenays’ rugged past

Kootenay Home: A prize collection of historic images shares the Kootenays’ rugged past

Growing up in the Kootenays in the 1950s and 1960s, I was blissfully unaware of many facts about my mountain home. Thanks to this superb photographic history I now can correct the many wrong assumptions of my youth.

First on the list are the Ktunaxa and Sinixt First Nations. They were fishing and hunting in the Kootenays thousands of years before any European settlers arrived to destroy their way of life. Authors Brighton and Nesteroff repeatedly stress this point as they usher in stunning images from their personal collections and other archives.

One example is the pictographs, 13 sets of them that appear around Slocan Lake. These are mostly accessible by water, so I missed them. They would have added to the childhood thrills of travelling through the Slocan Valley with its rock tunnel on the old road.

As the authors correctly note, the valley is unceded territory of the Sinixt Nation, which continues to battle for recognition after being declared extinct in 1956. And there’s more that I didn’t know. At least a dozen First Nations references appear.

Respected Ktunaxa leader Chief Isadore is shown, for example, with the text detailing his 1887 land dispute. The legendary Sam Steele of the Northwest Mounted settled it, but not in the chief’s favour. Steele gets into the history books, but who has heard of the equally legendary chief in Kootenay history? He can now claim his rightful place thanks to Lost Kootenays.

The Doukhobors, too, are allotted deserved space in this brief history, but not always favourably. The sect displaced a Sinixt family called Pic Ah Kelowna or White Grizzly. The family refused to leave the land Doukhobor farmers had purchased, so the farmers fenced them in and ploughed “their burial grounds.”

Of course, the Doukhobors had their own problems as Lost Kootenays documents. The death of leader Peter V. Verigin in a 1924 train explosion is recalled, as is a prayer meeting outside a communal house in Ootischenia. There’s also a wide shot encompassing the Brilliant jam factory along with other evidence of the industrious but often persecuted sect.

The old Doukhobor suspension bridge across the Kootenay River is pictured prompting many personal memories of crossing it in the days when the old Robson ferry (also shown) was still operating. It ran from 1919 until 1988. I’ll always remember the sign as I drove across the narrow span — “Strictly prohibited: smoking and trespassing with firearms.”

The many Kootenay sternwheelers are also here in their splendour. The SS Moyie (now a museum at Kalso) and SS Minto (longest running) are in several photos. Sadly, I recall seeing photos of the Minto being burnt on the Arrow Lakes in 1968 after a failed attempt to convert it into a museum. One final note on ferries: the SS Nasookin was brought ashore in 1947 and turned into a private home on Kootenay Lake that I once considered buying.

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) is depicted in several shots. The old train station, long a museum in my hometown of Castlegar, was graced with the presence of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip in 1971 during the BC centennial. I learned from Lost Kootenays that the station is the city’s oldest heritage building.

The CPR, with its Trail smelter and several local mines, plays a central role in the regional history and it gets its due here. Early on, ferries were part of that role as were many hotels. Take the Munro in Creston (surviving as the Kokanee Inn), the Queens in Hosmer, a coal mining company town, and the recently expanded Mount Stephen House in Field. Perhaps most striking is Glacier House, a “world class tourist destination” and dining stop for train travellers seeing the alpine sights in Glacier National Park.

There’s more about the CPR, including the high trestled bridge between Revelstoke and Golden that it had constructed, and the towns it built and displaced in the rush to serve the mines and smelters that made the Kootenays what they are today.

More, too, about the Chinese labourers who helped build the CPR’s main line “often at great personal risk.” Less known is their role in building the canal at Canal Flats in 1887. Two years of labour were wasted; the canal was hardly used. In 1894, South Asians were hired by the railway company to supply lumber for rail ties as labourers at the Golden Lumber Company in Golden.

The authors have added a succinct chronology of the region that offers a quick review of the history, supplying some facts in addition to those found with each photo caption. The captions, by the way, are written with care and precision. The authors have done a masterful job of fitting a lot of information into a tight space.

Lost Kootenays has filled in some of the historical gaps in my appreciation of the Kootenays and given all readers much to ponder about this small but fascinating part of Western Canada’s past. Careful research, a Nesteroff attribute that has often benefitted me, shows up some official errors and provides details that only these intrepid local historians are likely to unearth.

Those who have enjoyed the popular Lost Kootenays Facebook website will also enjoy holding this printed replica of some of the site’s many posts. If you are from or of the Kootenays, as I am, you’ll enjoy the trip down memory lane. And, like me, you’ll learn a few things along the way.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker, recently moved to Victoria. His work has appeared in The Ormsby Review since it was founded in 2016. Editor’s note: His book Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for Its Life in Wartime Western Canada will be published by University of Toronto Press early in 2022. See here for Ron’s essay on Trade Unionist Harvey Murphy and here for Mike Sasges’ review of Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb. Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Nick Russell, Jim Christy, John Jensen, Charlie Hodge & Dan McGauley, Ravi Malhotra & Benjamin Isitt, Allan Bartley, Eric Sager, Michael Dupuis & Michael Kluckner, Elizabeth May, Rosa Jordan, and Vera Maloff for The Ormsby Review. All his reviews may be viewed here.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1269 A choice Kootenay collection”