Love letters to locally sourced

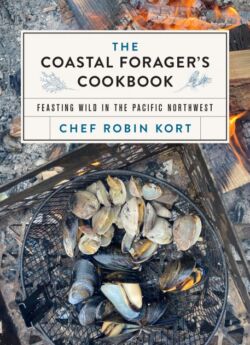

The Coastal Forager’s Cookbook

by Chef Robin Kort

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2023

$40 / 9781771514088

The Coastal Forager’s Pocket Guide

by Chef Robin Kort

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2023

$10 / 9781771514170

Reviewed by Theresa Kishkan

*

Although I’ve gathered wild berries – blueberries, salal, Oregon grape, blackberries – since childhood, it wasn’t until I was a young woman living on a remote island off the Irish coast, with almost no money, that I learned to forage for foods to supplement the five-pound sacks of lentils and brown rice I’d brought to the island in my rucksack. Nettles grew in wild profusion around the cottage I rented for a year. Mussels clung to the rocks below the cottage and I ate those too, though I was mostly a vegetarian. An elderly woman showed me edible greens—silverweed, peppery cress in a damp area half a mile away, and wild garlic grew in the hedgerows, along with cowslips and wood sorrel. Chondrus crispus, an edible red seaweed, (Carraigin, in Irish), was gathered by islanders to dry for their own use and as a cash crop and I was shown how to cook it in milk with a little sugar for a pudding.

My interest in wild foods has continued over four decades. I gather mushrooms, a selection of spring and summer greens, the occasional bucket of oysters, and berries for jams, syrups, and jellies. In our house, pizza is topped with dandelions greens, chickweed, lamb’s quarters, and buckhorn plantain. I let the Italian chicory go to seed and harvest the tiny volunteers for salad and soup. Miner’s lettuce also self-sows among the kitchen herbs. We eat green pie or hortopita year-round, those wildings supplemented with garden kale or spinach.

Chef Robin Kort’s beautiful The Coastal Forager’s Cookbook celebrates wild harvests and provides excellent recipes for using the foods around us. “Nothing feels better than knowing how to move with the wilder world.” She asks us to consider the ethics of foraging: “There is a good way to harvest each and every seaweed, wild plant, and sea creature. Please take the time to learn about how to honorably harvest before you pull, cut, or pick.” Her recipes are imaginative and innovative. Dandelion marmalade? It sounds delicious! Evergreen ice-cream? I’ve made ice-cream with rosemary and suspect this one will be similar, but more citrusy, worth pinching some new tips of Douglas firs all around my house as well as the grand firs along a trail I walk regularly. And the pineapple weed and blueberry panna cotta? I’m going to make that. Some of the seafood recipes are aspirational. I don’t know that I’ll actually attempt her Laphroaig clam chowder but I recognize the affinity of peaty single-malt with its salty notes and shellfish so maybe just adding a dram or two to my own seafood chowder could serve as a homage to Kort.

The Coastal Forager’s Cookbook is organized by season, beginning with Spring; each section begins with a short informative essay. Sometimes the recipes are built around a particular wild ingredient—bull kelp pickles for example – and sometimes the foraged element is more of a flavouring, albeit a lovely one: a handful of sea asparagus flavours a gazpacho, providing “a satisfying, salty, grassy taste similar to a green bean,” though a suggested substitution is asparagus, quite a different taste. In summer, there’s a thimbleberry jam to have with scones; and there are many recipes featuring mushrooms in the fall. Several, using reliable chanterelles, sound fabulous. A pate is a bit more complicated but made with vegetable stock, it could serve as the centrepiece of a terrific vegetarian feast. The Winter section relies heavily on the ocean. If you’re a winter swimmer, the opening essay will inspire you to harvest sea urchin, oysters, sea cucumber, limpets (I ate these in Ireland too, along with winkles!), and red rock crab. If you’re lucky, you’ll have the makings for the Juniper Fish Stew.

Seasonal foraging charts at the back of the book are helpful, as is the chart detailing substitutions for foraged ingredients. There are two pages of resources, somewhat cursory, and heavy on the author’s own courses; this section could be a lot more comprehensive. Also, at the back of the book, a few lined pages for notes, though it’s unlikely one would take such a beautiful book into the wild when there are so many laminated field guides available. Small quibbles, I know, but they feel like surprising missteps in a book otherwise so surefooted and confident.

Those of us lucky enough to live on the west coast have access to ingredients, both wild and prepared, that are expressions of weather, geography, ancient and modern farming techniques, and something else: genius loci, or spirit of place. From distillers using local botanicals to producers flavouring naturally harvested sea salts with bigleaf maple smoke or kelp to cheesemakers showcasing specific herbs and other aromatics, our markets and farmsteads provide us with such riches. And those riches, along with wild harvests, have resulted in a food culture that is often truly magnificent. The Coastal Forager’s Cookbook is a welcome addition to this particular discourse, a book that is as visually attractive as it is practical and usable.

***

A few weeks after writing about the The Coastal Forager’s Cookbook, I received a copy of the The Coastal Forager’s Pocket Guide, also by Chef Robin Kort, in the mail. It’s a laminated accordion-fold, with good photographs. As a companion to the cookbook, it’s helpful, to a point, but also deceptively titled: it’s a pocket guide to seafoods only. There are no mushrooms, trees, shrubs, or wildflowers, ingredients required for the recipes in the cookbook. But it’s something that could be part of a portable library of resource books you’d carry with you on a foraging trip. I’d recommend a couple of the Lone Pine field guides (Plants of Coastal British Columbia, ed. Pojar and MacKinnon, for example), a selection of the excellent Royal British Columbia Museum handbooks, including Mushrooms of British Columbia (ed. MacKinnon and Luther) and Nancy Turner’s iconic Food Plants of Coastal First Peoples, which provides such important cultural context, and some of Harbour Publishing’s Field Guide Brochures, including the ones covering edible mushrooms, seaweeds, and trees. Having several sources allows you to cross-reference, an important safety consideration.

*

Theresa Kishkan lives on the Sechelt Peninsula with her husband, John Pass. She has published 16 books, most recently two novellas, Winter Wren (Fish Gotta Swim Editions, 2016) and The Weight of the Heart (Palimpsest Press, 2020), as well as Euclid’s Orchard (Mother Tongue Publishing, 2017) and Blue Portugal and Other Essays (University of Alberta Press, 2022). She runs a small press devoted to the literary novella, Fish Gotta Swim Editions, with her friend Anik See. Editor’s note: Theresa Kishkan has also reviewed books by Y-Dang Troeung, Sasha Colby, Maleea Acker, Catriona Sandilands, and Mona Fertig for The British Columbia Review. Her book Winter Wren was reviewed by Miranda Marini; The Weight of the Heart by David Stouck; Euclid’s Orchard by Catriona Sandilands; and Blue Portugal by Michael Hayward.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster