1590 The art of looking

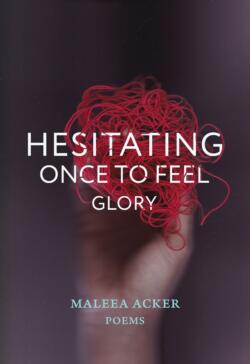

Hesitating Once to Feel Glory

by Maleea Acker

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2022

$19.95 / 9780889714144

Reviewed by Theresa Kishkan

*

This is how the title poem in Maleea Acker’s new poetry collection, Hesitating Once To Feel Glory, begins:

This is how the title poem in Maleea Acker’s new poetry collection, Hesitating Once To Feel Glory, begins:

Sometimes I think we can see

the world before it began,

and that’s what makes us

so sad. Before the world began

there were swallows flying

across a lakeside field

as the sun allowed the trees to shade it.

There were fallen leaves

from dry seasons that made

a golden road.

We follow the trajectory of the swallows in dappled light, their route shadowing the golden road, and we realize that this is a poet filled with attention and yearning. Her keen ear for the possibilities of movement within the lines themselves, how she slows the rhythm to accommodate the long glide of swallow wings — these allow us a physical experience that correlates with her own. Our reading of the poem is shaped by this care and craft. These qualities are found over and over in the collection.

I first encountered Maleea Acker’s work in the late 1990s. A small chapbook came into my house, Her Own Rituals, published by Smoking Lung Press in 1997. I remember the last poem, an astonishing love poem, in which a woman and a man see one another for the first time. They might be the poet’s grandparents, or their grandparents. No matter. One of them is standing on the street and the other is inside, by a window:

And do you know what he does? He turns

and he sees her at the window,

just standing there looking out at him.

And that is it for both of them, you know,

that is it.

A history, a family, a long story reaching into the future: these begin with this glance. The acuity of Acker’s observation is what I noticed all those years ago. I found it again in her book The Reflecting Pool (Pedlar Press, 2009):

The pin enters to carve the hole

In the wood of a window frame.

Ballast for roses, letter, card.

Wood moves aside for metal and holds,

Waits. One hundred years go by.

Again, in Air-Proof Green (Pedlar Press, 2013):

…a mare gives one glance, then returns

to the shade of the planted pines, her foal lying in sun studying

his own hooves in the mud. Sometimes a rift in life

cannot be turned into poetry; it sits in the sun

and takes and takes and takes the light until birds burst from it.

This is a wonderful cluster of images, particularly that “foal studying/ his own hooves in the mud.” The reader revels in the stillness, the tenderness, and when the unexpected happens, birds bursting from the light, it is all the more appreciated for the meditative moment that generated it. I return to the earlier books for these precise and delicate surprises within them. The work reads true.

Her new collection embodies the art of looking. A brief glance, in which a future is reflected; or a careful study, everything taken in, remembered, and savoured: “So, Imaginary/ do you recognize me still?/ Our letters down to three lines…” Sometimes we are in Mexico, hungry for the tacos she describes so lovingly:

Tacos!

Radishes float like little wounded hearts.

I am a compass needle swinging

yes to everything.

When she finishes them, she is “an unmatched sock again,/ old love silent at the other end of the country.” But still her scrutiny takes in so much of the world around her:

…the strangled look a man gives

to the air when presented

with the affection of a woman, a mule

with a wooden saddle, a mule loaded

to the traces with sorrow but

never, ever, no,

never with regret.

In another of the poems set in Mexico, the reader accompanies two people in a decrepit Ford as they drive and eat, pay rapt attention to each other and the water:

We drove to Rincón, a small turn between villages

where the road grows dark and the wetland spills under cliffs

and crickets, pelicans and ibises stretch themselves into filigree.

Every detail is rich, cumulative. “The west wind faded and bats flew over us.” As lovely as this is, we sense an ending, even as the two:

…faced outward and married one another’s arms

and fingers and heads to one another’s bodies, and it felt

like becoming a planet…

A planet, though, is singular, and the last line and a half of the poem remembers this:

… a planet, out in the dark, with a fragrant light

tearing out lives into pieces where each met the other’s edge.

The poems in Hesitating Once to Feel Glory are tender, dense with longing (“The body is an animal/ from which longing springs”), alert to potential grief, those singular planets, stars, and their collective light, and the torn lives; the poet in her observing, is attentive, often anxious, prepared for the worst.

It is likely that my father and my dog

will die the same year. They are both

in their retirement. They complain.

They smile. They look as if

they wish there were something

more they could do for me.

This thread of anxiety runs through the collection, an underlying note in the vividly observed moments, the poet’s commemorations of sunlight in a field, the inner beauty of a geode (“…an inner chamber/ of intricate light, of arc, of gold”). The lover who will leave, the father and the dog who will die, even the beloved places, perhaps damaged beyond repair: the poems focus attention as though that in itself might help. In an interview in the Miramichi Review, Nathaniel Moore asks Maleea Acker about the title of her new collection and her reply is frank and illuminating:

I use Matthew Zapruder’s image of the black crater in the book to similarly speak of depression and especially anxiety, which is a huge part of my life. The title speaks to this because it speaks to what might otherwise be possible in a life, were there not always these hesitations…

The book’s dark cover, the tangled ball of red string – both are suggestive of uncertainty and yes, anxiety. But also such possibility! I think of the etymology of clue, which comes from the late Middle English clew, a ball of thread, a means to guide one out of a labyrinth. It might be dangerous to untangle the string, to attempt to find a way out of despair, but it might also be illuminating. As she writes in the gorgeous poem “Curtain”,

The wind knocks the lakeside tansy and sorrel down.

We need not fall apart to feel the feeling.

Hesitating Once to Feel Glory inventories lost moments, lost love, friendships perhaps frayed or diminished over time (“I started reading your books in hopes/ of a secret message in the lines”), the passing of time, and it makes of these losses an archive of beauty. They are bound together by red string, untangled now, still usable after its journey to the labyrinth, the dark crater. The stories held so carefully in this archive are ours to share, through the generosity of the poet:

the maintenance man, readying

Frank Island’s love cabins with Presto logs

and a cooler of champagne…

and those “taken in the night, walking/ under jasmine, the cupola, the bóveda”, the piano teacher with her collection of dolls, the “children/ careening from the rubble of cars” in the marvellous “Automatic Pilot”, the ending of which provides a perfect conclusion to this review:

I am the operator of those incessant

tappings you hear at night while trying

to sleep the sleep before the interview.

I am the interviewer. Please believe me.

My galaxy became sad. I, too, wanted to be yours.

*

Theresa Kishkan lives on the Sechelt Peninsula with her husband, John Pass. She has published 16 books, most recently two novellas, Winter Wren (Fish Gotta Swim Editions, 2016) and The Weight of the Heart (Palimpsest Press, 2020), as well as Euclid’s Orchard (Mother Tongue Publishing, 2017) and Blue Portugal and Other Essays (University of Alberta Press, 2022). She runs a small press devoted to the literary novella, Fish Gotta Swim Editions, with her friend Anik See. Editor’s note: Theresa Kishkan has also reviewed books by Catriona Sandilands and Mona Fertig for The British Columbia Review. Her book Winter Wren was reviewed by Miranda Marini; The Weight of the Heart by David Stouck; Euclid’s Orchard by Catriona Sandilands; and Blue Portugal by Michael Hayward.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1590 The art of looking”