‘Strands of a life’

Landbridge [life in fragments]

by Y-Dang Troeung

Toronto: Alchemy by Knopf Canada, 2023

$35.00 / 9781039008762

Reviewed by Theresa Kishkan

*

When I opened this beautifully-designed book, with its cover drawings of delicate buds of kapok (in Khmer, Y-Dang Troeung tells us, planting a kapok tree, which makes no sound in the wind, is an act of “knowing, being, and surviving”), I was drawn to the endpapers first of all. Six vertical rows of words, almost all of them contained within square brackets, the same brackets used to contain the subtitle on the cover. The exceptions were ‘Dearest Kai,’ appearing 12 times: a refrain in this almost-poem. I spent a few minutes reading the rows across and down, looking for a pattern. In a way, it was a prudent way to begin. Good book designers – covers; jackets; text design, including typeface and size of font; spines, which are often the first thing we notice on a shelf in a bookstore – deserve our attention and respect. Emma Dolan’s work on Landbridge is first-class.

Landbridge is a memoir, strands of a life brought to the light. There is no through-line in this book, no beginning, middle, end—or at least there isn’t, not in the usual way we look for these things in a book and find them in the structure of the work. When I began to read, I noticed the titles for each section: [preface], [portrait], [transport], [currency], and so on. I realized the endpapers serve as a table of contents, a guidebook, a map. If we are alert, they help us to read in a nuanced way. The sections are often brief, a page in length; some of them include photographs. We see the author with her mother in a refugee camp in Thailand, where her parents arrived after walking from their home in Kampong Thom, Cambodia, after soldiers of the Khmer Rouge marched into the city. The entries reflect their titles in ways that are unexpected; they make sense as poems make sense; they are not linear expositions but distillations of experience and meaning. In [black holes], Y-Dang Troeung recounts a session with her therapist, many years after her family has left the refugee camp, and had made a life in Ontario. The author was educated, married, had a child, (Kai, for whom she writes tender letters), and her therapist asks how it feels to carry the work of documenting her life set within the history of Cambodia.

How to express the effect of listening, reading, writing, and translating these accounts for a decade as a researcher, and for a lifetime as a daughter? The barrier between myself and the work sometimes feels so thin, the furthest thing from the lens of a neutral observer. I know there is a cost to knowing, but I don’t know how this cost has been paid by me personally.

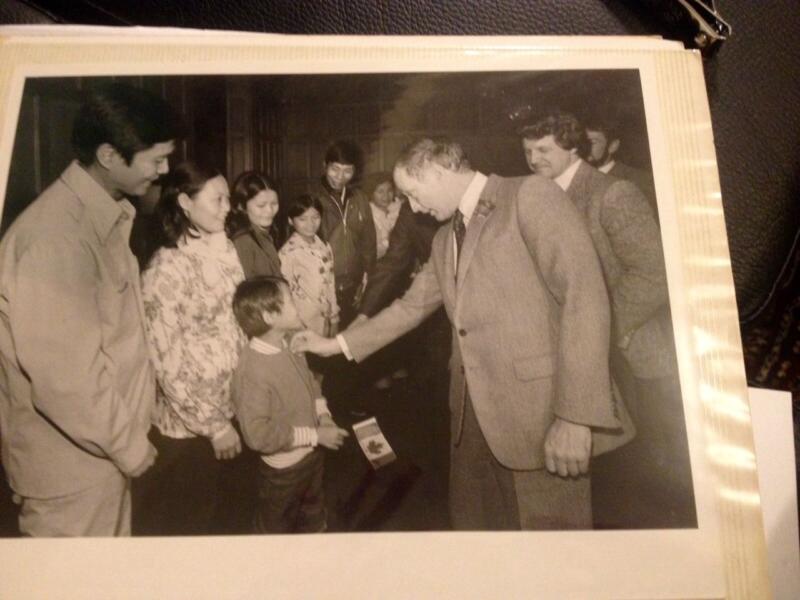

Troeung’s life in fragments is scattered through time. Her family’s life in Cambodia before her birth, the camp, their arrival in Canada heralded by media (they were the last of the 60,000 brought to this country as part of the Indochinese Refugee Program and Troeung was famously photographed with Pierre Elliott Trudeau as an infant) are showcased. So too is her work in later years as a scholar and researcher in the areas of transnational Asian studies, migration and refugee discourse, and critical disability studies. These are interesting in themselves but they also accrete, become building blocks, functioning as a kind of literary architecture. Some readers might miss a straightforward narrative but I found Troeung’s fragments to be an effective way to explore a life that has not had a traditionally linear progression.

She is not easy on a complacent reader with her observations about the expectations of refugees. That they smile, that they are eternally grateful, that they work hard, make their sponsors proud. Or in the involvements of foreign governments in the Cambodian genocide. A transcript from the Kissinger Telcons is particularly harrowing: in the course of a brief conversation on December 9, 1970, Henry Kissinger instructs General Alexander Haig to carry out B-52 bombing of Cambodia. In an account of a conference in Phnom Penh, during which Western scholars explain Cambodia’s history to Troeung and other Cambodians, a young student finally stands up to comment: “I appreciate your analysis and look forward to reading your book, if it will be made available here. But I would like to ask you now, Where was your country when the genocide was happening?” Reading that, I couldn’t help but think of the current war in Ukraine and how we live in the echo of our parents’ assertions, after the Second World War: Never again. We live in the echo as Troeung visits the War Museum Cambodia, a museum guide telling the group he is taking around the exhibits, “They took away my family and then they killed them. I ate the crickets, grasshoppers, frog, fish, snake, everything. A hornet’s nest dropped down on me. I live thirty miles north from here. About fifty kilometers. My wife died three years ago. Lung cancer from the uranium. On April 16, 2017, my friend stepped on a mine and it took off his legs.” We read and we feel the compounded grief of Troeung and her family and everyone who escaped, or didn’t. And the shadow that hovers over the book is Troeung’s own diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. She died before her book was published.

Landbridge makes excellent use of documentary materials throughout, including family photographs and archival ones. Several of the fragments, including [app], trace the search by Troeung’s mother’s for a brother who disappeared during the genocide. The memories shared by her parents of the early days of their marriage, including a visit to a fortune teller who foresees a dark time in Cambodia, are very moving. This section, [wandering soul], distills so much of the personal traumas of a family during war.

My mother’s last image of my grandmother was of her being taking away by the Khmer Rouge. Because she sixty years, considered elderly, she was of no use to the regime…My mother wept. She could see her mother’s body and could not perform a proper Buddhist cremation ritual. My mother believed her mother’s ghost would remain in the world, alone, restlessly wandering the earth.

The section [landbridge] offers a brief meditation on the meaning of this biogeographical term. It “refers to a strip of land that forms across an expanse of water, linking two previously unconnected land masses. The formation of a land bridge allows for a new circuit of migration to take shape.” As I was reading this section, and the book as a whole, I was grateful for the phrases written in Fujian, in Khmer, and other languages; in a sense they provide a bridge that takes the reader across time, through history, a world dense with ghosts, with echoes, and with sorrow, and also with hope. On the last page, in a letter to her son, Troeung writes

Remember that, as your grandparents once taught me, when we have nothing, when we are fleeing the soldiers and the bombs, when we are cut off from the rest of the world and each other, we still find some way to come together. With only our bodies and our hearts, we build a bridge.

Troeung’s family photographed with then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. They were the last of the 60,000 brought to Canada as part of the Indochinese Refugee Program. Courtesy Visual Stories Blog, State of Refuge by Thy Phu (PI) and Y-Dang Troeung

*

Theresa Kishkan lives on the Sechelt Peninsula with her husband, John Pass. She has published 16 books, most recently two novellas, Winter Wren (Fish Gotta Swim Editions, 2016) and The Weight of the Heart (Palimpsest Press, 2020), as well as Euclid’s Orchard (Mother Tongue Publishing, 2017) and Blue Portugal and Other Essays (University of Alberta Press, 2022). She runs a small press devoted to the literary novella, Fish Gotta Swim Editions, with her friend Anik See. Editor’s note: Theresa Kishkan has also reviewed books by Sasha Colby, Maleea Acker, Catriona Sandilands and Mona Fertig for The British Columbia Review. Her book Winter Wren was reviewed by Miranda Marini; The Weight of the Heart by David Stouck; Euclid’s Orchard by Catriona Sandilands; and Blue Portugal by Michael Hayward.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “‘Strands of a life’”