1952 Heartbreak and ‘passages of such beauty’

The World is But a Broken Heart

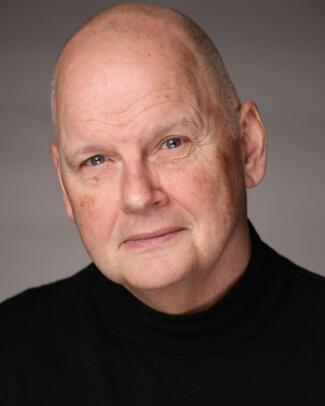

by Michael Maitland

Winnipeg: Signature Editions, 2023

$19.95 / 9781773241296

Reviewed by Heidi Greco

*

As the title suggests, The World is But a Broken Heart is not a cheery book. In fact, the linked stories in this debut collection reveal a family for whom just about everything that can go wrong does exactly that.

As the title suggests, The World is But a Broken Heart is not a cheery book. In fact, the linked stories in this debut collection reveal a family for whom just about everything that can go wrong does exactly that.

Henry works in a mind-dulling job at a slaughterhouse in Alberta. It’s a place where “Happiness had nothing to do with hope. Hope was found in a weekly lottery ticket, success an apprenticeship or a steady job in the oil patch.”

He and his wife Maureen have three sons, brothers who scrap with each other, just as their parents do: “…she listens to the familiar snapping and creaking of Henry coming down the stairs. With each step, Maureen senses the habitual acrimony they share steal down behind him. Over the years, Henry has put a fist through the drywall. He’s thrown cups and plates, cursed at her and the boys until he was blue in the face, although, lucky for him, he’s never raised a fist to her, or threatened to, even when they’ve been spitting venom at each other.”

Life isn’t easy, not even with Henry’s union job and Maureen doing cash at the local Safeway. But when Henry decides that he needs to move up the ladder, conflicts in the family only grow. Nevertheless, Henry steps away from the security of the union to become a foreman. And this is when, just as Maureen had argued they would, things start to go south for all of them.

Sure enough, it isn’t long until there’s a strike—an event that pits the father and his family even further against each other. When scab workers are brought in, along with riot-geared patrols, things get uglier:

“Men with arms as thick as logs and a thirst for beer and justice, wearing toques and Oilers caps, their bodies warm with worn winter jacket and thick flannel lumberjack shirts, their skin damp under their clothes, gather in preparation for the daily battle. Jockstraps and cups are worn over blue jeans.”

The divisions between the greedy, pig-headed owner of the plant and the poor-fuck striking workers seem impossible to bridge. Maitland describes the situation as being one “…where there are two types of men; men, and men who make their money off the backs of other men.”

And as for those strikebreakers—immigrants, desperate for work—they’re the butt of every kind of slur you can imagine. If you’re a reader who’ll be offended by racist name-calling, you’d better check your hat at the door, as Victoria-based Maitland lets his characters speak the way real people do (or did). In truth, I wouldn’t be at all surprised to know that quite a few folks still do. Such dialogue is just another aspect of the convincingly real scenes the author conjures.

Maitland’s Alberta is not only believable, but can be downright grim. I was sometimes taken aback by a device that Maitland uses—an odd kind of a technique I can only call ‘dark foreshadowing.’ Every once in a while he slips in a quick mention of a huge plot point (one that’s negative, and in a big way) that hasn’t yet occurred. This usually appears in the midst of simple exposition. And then sure enough, some while later, said horrible event that was alluded to occurs.

In a hideous kind of life-imitating-art scenario, recent news included a story that one of the book’s major tragedies seems to echo. And now this morning, yet another freakish incident has occurred. Coincidence? I suppose, though I’m not sure I want Maitland fashioning any new work around details from my life. Something about such realistically harsh events give me pause; they scare me as a little bit eerie in what looks like prescience.

On the other hand, despite freakish tragedies, there are passages of such beauty, you want to take a freeze-frame, as in this scene from a silent car ride, father and son:

“The urban sprawl had long surrendered to farmland with its rolling hills and ravines lined with copses of lodgepole and jack pine, poplar and willow trees, flat farmers’ fields brimful of spring wheat, barley, and alfalfa. Abandoned sheds, their wood exteriors grey with age, stood canted from the wind. A fox sat still on a rise and sniffed the air. Black and white magpies and other scavenger birds ragged across the clear blue sky or sat patiently on fence posts along the side of the road…”

Although there are few continuity glitches that left me turning back pages to look for what I must have missed, the writing is solid; I feel that I know these people, and that they are more than mere fictions—they’re real. That’s probably why their heartbreaks are ones I experienced so deeply.

As the mother of sons, I can vouch for the book’s perceptive descriptions of the often up-and-down relationship between brothers—along with the depth of caring that underlies those squabbles even when they can occasionally seem cruel. And as a reader who perhaps becomes too involved with what’s on the page, I can only caution you about this powerful book: it’s going to stay with you, perhaps longer than you’d like. But then, as one of the characters says, in what feels like a moment of wisdom, “What’s the world without a broken heart, eh?”

*

Heidi Greco lives in Surrey, where some would contend she can often still be found to be tilting at windmills. [Editor’s note: Heidi Greco has recently reviewed an exhibit by Douglas Coupland and books by David Zieroth, Christine Lowther, Rhona McAdam, Richard Lemm, Souvankham Thammavongsa, Marguerite Pigeon, and John Gould for The British Columbia Review. Three of her books have also been reviewed here: Glorious Birds: A Celebratory Homage to Harold and Maude (Anvil, 2021), by Linda Rogers; From the Heart of it All: Ten Years of Writing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Otter Press, 2018), by Yvonne Blomer; and Practical Anxiety (Inanna, 2018), reviewed by Andrew Parkin.]

Heidi Greco lives in Surrey, where some would contend she can often still be found to be tilting at windmills. [Editor’s note: Heidi Greco has recently reviewed an exhibit by Douglas Coupland and books by David Zieroth, Christine Lowther, Rhona McAdam, Richard Lemm, Souvankham Thammavongsa, Marguerite Pigeon, and John Gould for The British Columbia Review. Three of her books have also been reviewed here: Glorious Birds: A Celebratory Homage to Harold and Maude (Anvil, 2021), by Linda Rogers; From the Heart of it All: Ten Years of Writing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Otter Press, 2018), by Yvonne Blomer; and Practical Anxiety (Inanna, 2018), reviewed by Andrew Parkin.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1952 Heartbreak and ‘passages of such beauty’”