1840 ‘Provocatively brilliant for the right reader’

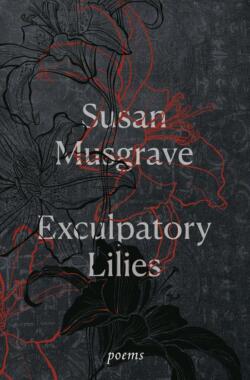

Exculpatory Lilies

By Susan Musgrave

Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2023

$22.95 / 9780771099007

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

How do we convert the pain of loss into poetry? Grief over the death of a friend or lover or a family member is a common enough theme throughout poetry of every era and has often, in Lycidas or In Memoriam, produced elegiac masterpieces. In one sense, then, Susan Musgrave’s grief for a dead husband and for her daughter is familiar territory. But not in the way she does it.

How do we convert the pain of loss into poetry? Grief over the death of a friend or lover or a family member is a common enough theme throughout poetry of every era and has often, in Lycidas or In Memoriam, produced elegiac masterpieces. In one sense, then, Susan Musgrave’s grief for a dead husband and for her daughter is familiar territory. But not in the way she does it.

Whatever some may think of the preoccupations and attitudes of her latest work there is no denying that Musgrave is writing at the height of her poetic powers. This is true both technically and emotionally. Technically, we find images that capture with precision the colour of an eagle’s eyes —“of late sun falling on wild grasses”—and in the deft, witty way she handles line breaks, as in, “I didn’t know, then, our love was doomed / to last.” To these qualities one might add an important element in poetry, surprise, so that in “What we really want,” quoted here in full, a commonplace marital situation turns into a seemingly matter of fact personal confession at the end:

It took you ten years to tell me,

I don’t like parsley. Next came dill,

five years later. Does this have lemon

in it?, you asked, only last autumn, poking

unhappily at a marinating breast. We have

had a long life together, my love. I knew

from the start you never liked anything

over-easy: when it came to marriage

we had reached an accommodation. Now

it’s death I can’t fathom.

Emotionally, she runs the gamut of responses to death and dying, nowhere telling her readers what to feel but making them feel it for themselves. So, while she is not able to “fathom” death, at the same time, she tells us in “Patience” that she is equally not looking for comforting abstractions. Thus, when visiting her granddaughter’s classroom, she finds a poster of Virtues: the Gifts of Character—a list of 52 positive (subjective at best) traits, each one a vague abstraction. Musgrave comments, “I go / in fear of abstractions and worry / for my granddaughter’s future, that she won’t grow up / being able to show not tell, but embrace, instead, dim / concepts like Enthusiasm, Excellence and Service. / Lucca is five; how will Enthusiasm help her cope / when she finds her white cat in a ditch, a bib / of flies at its throat?”

Beyond such defiantly down to earth realism, I love the way her poetic mind works, especially in its alertness to language. Returning with her mother to an airport in Ireland Musgrave writes:

The signs point to Terminal 1

CARGO, MORTUARY, WAY OUT. Jesus, I think,

The Irish. The words airport and mortuary

have more than five letters in common; who needs

the mortal reminder at this time?

This keen sense of her surroundings, linguistic as well as topical, when combined with a mordant sense of humour (Musgrave’s poetry is a slaughterhouse for sacred cows) transforms episodes that could have been cringeworthy into moving insights. Here, in the fourth and final section of the sequence “The Goodness of This World,” she relates an episode involving her deceased, heroin-addicted daughter—

We got in the car and drove, trying to imagine –

had she been kicked out of her house, or had she run

away? Maybe she’d chucked everything

before checking into the rehab facility on the hill, hoping

to start anew? I didn’t want to go on, I wanted to turn back,

open the letters, find a clue, a name, an address to return

the things to, but you said it was useless and I could feel

the panic rising in you and I had little strength at that time

and I was driving and you need both hands

to hold someone who is suffering and who does not want to be held.

But such attention to detail would not matter were it not matched by a constant ruthless self-interrogation that is expressed in clear, everyday language.

The power of good poetry announces itself at first hearing and derives in part from its ability to articulate sometimes contradictory feelings and states of mind in a memorable way. One of the most difficult tasks for any poet is to find words that are not only direct and true but also individual and fresh. I think of Yeats’ “too long a sacrifice / can make a stone of the heart,” Elizabeth Bishop’s “The art of losing isn’t hard to learn,” Tennyson’s “t’is better to have loved and lost / than never to have loved at all,” or, most famous of all, Keats’ “Beauty is truth, truth beauty. That is all / Ye know on earth and all ye need to know.”

But it takes years of practice to be that simple and direct. A beginning poet cannot start a poem with lines like these and expect to be believed. For such dicta are not statements of scientifically verifiable fact. Rather, they are findings, affirmations, personal truths arrived at and rooted in the course of a lifetime, and to carry any weight they have to be built towards. The poet has to establish his or her bona fides or trustworthiness in what precedes them in the particular poem or in the whole oeuvre.

Over the course of a long, productive and often quite public literary career, Musgrave has earned that trust, so that time and again when she comes up with brilliant lines—such as “Don’t think / for a moment anybody cares. Suffering / only comes in two kinds. Yours. / And mine”—we are forced to believe her.

Often we find apparently familiar turns of phrase, even cliches, loaded with extra meaning. For example, one of a series of poems to her dead daughter ends with

My fault was in trying to fix you,

who taught me, all life on Earth is the dust of ruined stars.

Words for your headstone, carved by a hard-bitten wind

When the dust settles, we’re left with dust.

while elsewhere, in “Tears of Things” she concludes, “You cherish them, then they are / gone. What more can be said.” There is no question mark.

These are not statements but affirmations, findings. While I doubt that Susan Musgrave would welcome such lapidary and classical sounding a word as “wisdom” ascribed to her book, it is nonetheless true that how she handles her grief reveals a resilience that is heartening, interwoven with a wry, intimate understanding of what life’s changes mean as we grow older.

Her book, in short, is a roller-coaster, mixing the comic, the outrageous, and the brutally sad. Not a book for everyone, then, but provocatively brilliant for the right reader.

*

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. The most recent of his thirteen books of poetry are A Tattered Coat Upon a Stick (Quattro Books, 2017) and Small Talk (Silver Bow, 2022), reviewed here by Al Rempel. He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series. Editor’s note: Christopher Levenson has recently reviewed books by Katherine Lawrence, Leanne Boschman, Isa Milman, H.C. (Hans) ten Berge, John Barton, John Pass, and Rob Taylor.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1840 ‘Provocatively brilliant for the right reader’”