1233 Alert to the sound of language

This Was the River

by John Pass

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2019

$18.95 / 9781550178753

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

Winner of the 2006 Governor General’s Award for poetry for a previous volume, Stumbling in the Bloom, John Pass is, no doubt justifiably, dismissive in his opening poem, a kind of sonnet, of many of his fellow poets’ “limbless/ heaviness so many slip and wallow in; sour,/ opinionated Or busy in some worthy, tiresome way/ about the world, themselves.” Later, in “Cougar,” he writes “and you can stop saying as so often some way into so many/ present-day volumes of verse: Someone had an idea.” Such comments set the bar high for his own work.

Winner of the 2006 Governor General’s Award for poetry for a previous volume, Stumbling in the Bloom, John Pass is, no doubt justifiably, dismissive in his opening poem, a kind of sonnet, of many of his fellow poets’ “limbless/ heaviness so many slip and wallow in; sour,/ opinionated Or busy in some worthy, tiresome way/ about the world, themselves.” Later, in “Cougar,” he writes “and you can stop saying as so often some way into so many/ present-day volumes of verse: Someone had an idea.” Such comments set the bar high for his own work.

Not that anyone would dispute his sheer technical skill. A good poet relishes language in the same way that a painter rejoices in a blank canvas or an athlete an empty scoreboard. Take “Rereading My Notes re Rereading Clea in Venice:”

[My mind] inviting its gilt

and oils towards shimmer in darks a world away; flats

between leaf mulch and earth, the under-shadow

of salal edging rock bluff

Surprising though it may be to find such lines in the context of that most densely urban of cities, Venice, the justification he follows up with — “So I might go newly/ native in the soft wash and moss of the quiet city” — reveals at once that Pass is someone used to looking very closely at the natural world, someone we can trust to be accurate, in a way that recalls the Notebooks of Gerard Manley Hopkins.

So too with his handling of long, sinuous, sometimes syntactically complex run-on lines. Thus in “A cheering stain,” referring to long lost pet cat:

I’d say

Cloudy will always be with us

or some such facile nonsense

as the statistical engines grapple

with how high the oceans might rise

to the numberless human occasions

anticipated in 2100. How much of this

rainforest timber shroud will be tinder

or ash by then?

The hesitations, the caveats, the asides are all there and well managed. But while we can admire the dexterity, the indirection, do we feel caught up in the argument, as I assume we are meant to do? For me the notations seem almost telegraphic, a little too laconic, as if we are over-hearing, eavesdropping on, a thought process or notes for a lecture. Admittedly this provides a kind of immediacy but arguably at the expense of any sense of shaping.

With the section “Creation of the animals,” which comprises about a third of the book, the intensity of his commitment to, and skill in evoking, the natural world, whether it be elk, deer, bull, cougar, sapsucker or toad, immediately invites comparison with D.H. Lawrence, Mary Oliver, Ted Hughes and Norman MacCaig — to name only a few of the poets who have written movingly about animals. But there is always room for another good poem on any subject and Pass does not disappoint. Take for instance the first seven lines of “Dragonfly:”

Over the roofline little scuff

on the high brilliance. But moves

and not with the high breeze as seed

cluster or web might, but darts

and veers now into house shade, blue

needle, green darner in companionable zip

hither, over the gleaming car, back a bit, over

here, closer.

For this amazingly exact evocation of movement, Pass’s characteristically abrupt and clipped syntax is the perfect medium. Yet, as with fellow Canadian poet H. Masud Taj’s brilliant evocation of a dragonfly, the resulting poems, however insightful, seem more like field notes, scholarly and scientific rather than arising from affectionate engagement.

Unsurprisingly, Pass’s implicit subtext concerns potential extinction and climate change. Behind even the most innocuous seeming “nature” poem lurks an ecological message about “the same self-endangered stasis” and the albeit totally justified but nonetheless wearisome attack on human greed, the vanity of mankind’s “vaunted exceptionalism” and its responsibility for the state of the natural world. Thus in “Kinship:”

Dove circling,

circling… Apologies. Big enough beings

to lean to deep reflection, big enough to see

it’s us, us first, us filtering, we’ve sucked it up

to grant splayed subjects of the cast-off kingdoms

language, tools, exotic powers — specious

niggardly benefits of our guilt.

Some of the poems in the final section, picking up from “Margined Burying Beetle,” which describes the poet burying his mother’s ashes in midwinter, look back to childhood or adolescent memories or deal with such more obviously personal events and themes as the birth of grandchildren, but even here there is a detachment. Thus “Holding Arthur” interestingly — but again dispassionately — juxtaposes a fifteen day-old grandchild with an exhibition about Pompeii that the poet had visited the previous day. It concludes:

Holding his sleep-

ing breathing, as if holding the rest

of the world the day

after Pompeii

For the most part, the poetry maintains a deft counterpoint between wordplay, allusion and surface meaning. Occasionally though, he lapses into weak puns – “ball point (no bald point)” — or passages such as this from “Squirrel” where the wordplay and sound patterning seem gratuitous:

I know the seeds

of the dream I love to live in (the day upon day of worthy

work and better sleeping) are hard won and hidden

in aberrant being, abhorrent behaviour.

or these flamboyantly alliterative lines from “My Notes re Re-reading Clea in Venice:”

Clearer, or me more at ease over years intervening

with ambiguity? Magnificence and monument emerge

and merge in mist, marginally greyer than the whitish grey

daylight here canals curve or sway towards them.

Whereas in Kevin Spenst’s latest work, say, excess is an integral part of the overall performance, here the virtuoso effects strike me as intrusive.

If we ignore such occasional excesses, it is refreshing to find a contemporary poet so alert to the sound of language. At his best the muscular consonantal clusters, assonance and internal rhyme in “Coyote” recall another great nature poet, Hopkins. Like most good poetry, they need to be read aloud:

The bright ungainly landscapes/ sound

scapes scraping, tectonic pack hardly shifting

off centre-line roadkill in a lone car’s light

tunnel; wintry grunts and squeals unmistakably sex

slid downhill under us waking.

Likewise, whatever his theme or subject matter, Pass is almost always gloriously tactile. Take this from the title poem:

From muddled movement, mud

to step unexpectedly in to refreshment, swirled

pallet of eddy-boil, gravels and boulders, sure-

footed map of the island, adjacent picked

up in a seed-potato of pebble! Pine

root and cacti are hugging the clay banks

and sluices. Bunchgrass. Bird’s nest

in a small tree’s last gold

leaves. Scenes past season in new amber.

Is this enough? That will depend on the reader. Pass has massive talent, and all his poems, however challenging, are dense with meaning and repay close re-reading.

*

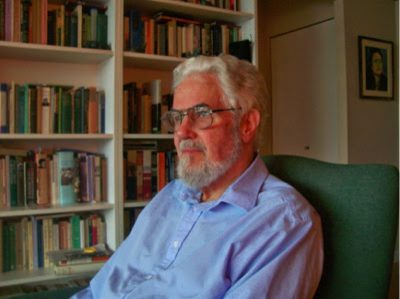

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. He has written twelve books of poetry, the most recent of which is A Tattered Coat Upon a Stick (Quattro Books, 2017). He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series. Editor’s note: Christopher Levenson has recently reviewed books by Rob Taylor, Kevin Spenst, Derk Wynand, Daniela Elza, Sarah de Leeuw, Susan Buis, Miranda Pearson, E.D. Blodgett, and Nicholas Bradley.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1233 Alert to the sound of language”