1836 Tender poetic ruminations

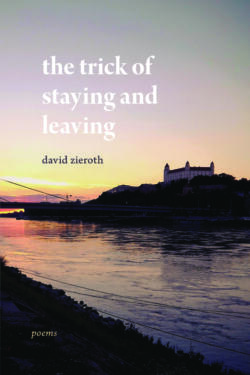

the trick of staying and leaving

by David Zieroth

Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2023

$22.95 / 9781990776021

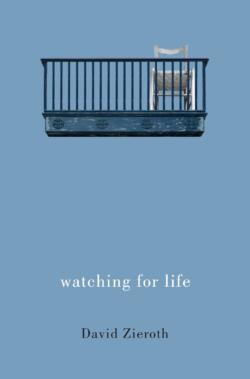

watching for life

by David Zieroth

Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022

$19.95 / 9780228014744

Reviewed by Heidi Greco

*

I can’t help but think that in a past life David Zieroth may well have been an explorer. My reason for this has nothing to do with psychic abilities, but rather North Vancouver’s Zieroth’s penchant for writing as if he is a traveller. When I say that, I don’t mean that he writes like some kind of tourist visiting an out-of-the-way country as he checks it off a bucket list, but as an avowed adventurer, seeking to immerse himself in a new experience, with eyes wide open, ready for whatever that culture may have to offer.

I can’t help but think that in a past life David Zieroth may well have been an explorer. My reason for this has nothing to do with psychic abilities, but rather North Vancouver’s Zieroth’s penchant for writing as if he is a traveller. When I say that, I don’t mean that he writes like some kind of tourist visiting an out-of-the-way country as he checks it off a bucket list, but as an avowed adventurer, seeking to immerse himself in a new experience, with eyes wide open, ready for whatever that culture may have to offer.

This point of view is sustained throughout both of his newest books (two in the course of less than two years—what an accomplishment!).

First stop on the newer of these books, the trick of staying and leaving, is basically the three-part journal of a trip to what’s now called Slovakia. Logically enough, these sections are ‘Arriving,’ ‘Staying,’ and ‘Leaving.’ He spends time in the old city of Bratislava, a place where we get a feel for the years of war and history as he walks us through the narrow streets. Yet in contrast to helping us feel the age of the city, he keeps us in the present day by asking his guide to please translate the graffiti he sees almost everywhere.

One of the more interesting aspects of his visit is Zieroth’s attempts at learning the language, and not just the mostly unreadable language of spray-painted tags.

we are underground in

the operný parking when I learn

east in Slovak is also exit:

východ the sign says, and I try

to repeat my friend’s pronunciation

and fail and try again, and fail

but, oh, that in Communist times

east with its meaning ‘the way out of here’

led to deeper Soviet confinement!

Three separate mini-sections introduce us to what he calls ‘Some useful Slovak words.’ These range from the always-important ‘please’ to abstractions such as the word for ‘soul,’ or to practical matters like ‘water’ and specific items of food. And of course food is on the agenda, surely one of the reasons many of us enjoy wandering afield, even when it means we have to point at what we’d like when we have no word for it. In one instance we see that his exploration of restaurants results in being able to share a ‘Western’ experience with his friend: sushi—a treat his European counterpart has never tried before—a cultural exchange of sorts, even if raw fish is not what one might think of as a specifically Canadian food. These are the stories told by a world traveller in a world grown smaller thanks to air travel.

Three separate mini-sections introduce us to what he calls ‘Some useful Slovak words.’ These range from the always-important ‘please’ to abstractions such as the word for ‘soul,’ or to practical matters like ‘water’ and specific items of food. And of course food is on the agenda, surely one of the reasons many of us enjoy wandering afield, even when it means we have to point at what we’d like when we have no word for it. In one instance we see that his exploration of restaurants results in being able to share a ‘Western’ experience with his friend: sushi—a treat his European counterpart has never tried before—a cultural exchange of sorts, even if raw fish is not what one might think of as a specifically Canadian food. These are the stories told by a world traveller in a world grown smaller thanks to air travel.

The Eastern Europe he shares with us is a land of sharp contrasts, as in this scene from a road trip in the country:

father and son up front joke

in language I can’t follow

while the radio alternates between Jagger

and Vivaldi, and so we pass harvested fields

and roadside shrines to the suffering

crucified Christ with fresh plastic flowers

then hilltop castle ruins, goldenrod and lupine

ageless in their wild places…

This traveller’s point of view extends into his other book, watching for life. The situation here is certainly less exotic, as it’s the world Zieroth views outside his third-floor apartment, the comings and goings in the laneway below him.

If such a notion seems restrictive, think again. The poet has discovered a richly varied vista beneath him.

He notices the people who pass beneath his suite, observing elements that might be missed, save for his vantage point above them, as in this piece titled perfectly, “Some men are striders, and here’s one”:

lanky long legs clipping like scissors

along the lane, carrying two sagging bags

from Persia Foods as if they’re weightless…

he lopes as if he were on stage

confident as a man in his prime can be

with lines to deliver, words

that will cause heads to turn…

More than mere description (as if that might not be enough), Zieroth offers his own imagined insights as to what the man’s purpose could be, opening realms of possibilities that pull us along down the lane.

Titles often serve not only as descriptors but also as introductory lines, an integral part of the poem, as in this almost-dreamlike piece, “I awake in the morning to find”

a large grey boulder has materialized

in the lane, where it blocks both cars

and pedestrians, its bulk so fierce

dogs draw back from their urge

to smell and mark, everyone

stunned by its presence…

The resolution to the poem resonates with mystery, unanswered questions that leave everyone with a story all their own—as, I suppose, any strong poem ought to.

He observes women with babies, teenagers glued to their phones, lovers entwined—oblivious to the rest of the world. Viewing seniors, he’s reminded of those gone before him, including his sister. His ruminations are tender, those of an empathetic man who’s truly human/humane.

But it’s not only people who draw his caring attention. The non-human passersby attract him just as much, especially the crows and pigeons. His thoughts about a shining crow lead him from watching the crow poke about for food to a kind of meditation on the nature of dark and light:

I think of his feathers, black black, how

they absorb light, the dark hole

he brings wherever he lands on earth

always a purity of disappearance

his piece of night that darkens day

Whether crows, or pigeons in the act of mating—even the lane itself demands his attention. He imagines a ship appearing there, full sail, notes the simplicity of the lane as a place without the artifice of borders imposed. One of the sweetest thoughts he offers about the lane is a wonderfully absurd request, “Dear City Fathers or Mothers or Planners,” where he asks that they “build a European fountain” there, making promises about how he would enjoy it, especially its sounds.

Absurd or not, if any lane has ever earned such an honour, the one beneath David Zieroth’s home has.

*

Heidi Greco lives in Surrey, where some would contend she can often still be found to be tilting at windmills. Editor’s note: Heidi Greco has recently reviewed an exhibit by Douglas Coupland and books by Christine Lowther, Rhona McAdam, Richard Lemm, Souvankham Thammavongsa, Marguerite Pigeon, and John Gould for The British Columbia Review. Three of her books have also been reviewed here: Glorious Birds: A Celebratory Homage to Harold and Maude (Anvil, 2021), by Linda Rogers; From the Heart of it All: Ten Years of Writing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Otter Press, 2018), by Yvonne Blomer; and Practical Anxiety (Inanna, 2018), reviewed by Andrew Parkin*

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1836 Tender poetic ruminations”