1652 The language of song

Questions to the Moon: Songs & Stories

by Earle Peach

Vancouver: Lazara Press, 2021

$20.00 / 9780920999158

Reviewed by Jeff Stychin

*

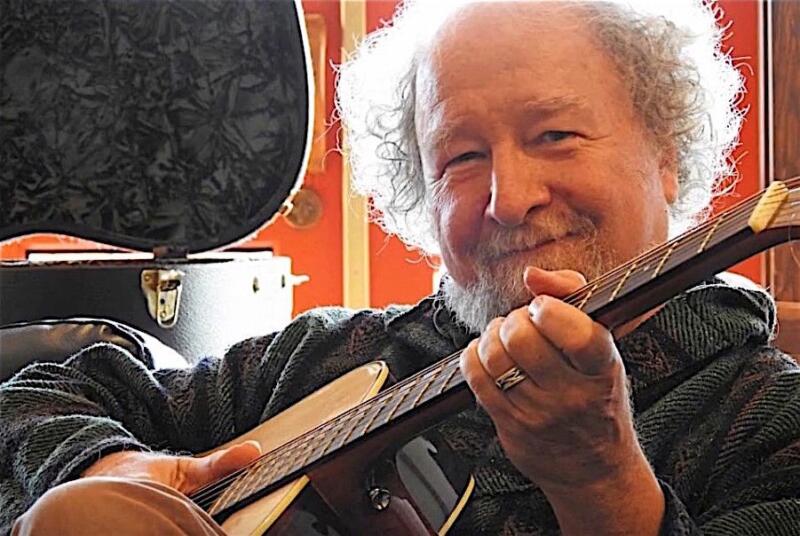

Earle Peach is a multi-instrumentalist, composer, and songwriter from Vancouver who directs choirs and plays in musical groups, volunteers at and hosts music events, pursues social activism, and is still actively involved in the folk music community. Peach always possessed a clear view of just what it means to be a songwriter amongst musicians. In Questions to the Moon, Peach begins by addressing the nature of composition, lyrics, and poetry in his music. “The first and most obvious difference I see between lyrics and poetry is that lyrics are worn easily by music. This is because, like music, they have an internal repeating rhythmic structure which they obey or disobey as seems appropriate” (p. 15).

is a multi-instrumentalist, composer, and songwriter from Vancouver who directs choirs and plays in musical groups, volunteers at and hosts music events, pursues social activism, and is still actively involved in the folk music community. Peach always possessed a clear view of just what it means to be a songwriter amongst musicians. In Questions to the Moon, Peach begins by addressing the nature of composition, lyrics, and poetry in his music. “The first and most obvious difference I see between lyrics and poetry is that lyrics are worn easily by music. This is because, like music, they have an internal repeating rhythmic structure which they obey or disobey as seems appropriate” (p. 15).

I’ve written poetry sporadically for years, but I had never thought about the complexity of lyrics before reading Peach’s book. I’ve always considered that music lyrics were connected to deeper meanings that the artist is trying to convey in addition to the musical accompaniment. The association Peach draws between lyrics and the rhyming word is profoundly intricate, as he explains: “Of course lyrics must also be about something, but in this they also differ from poetry because they have a different cultural history of style, rhythm and subject” (p.16). These concepts can create difficulty in execution:

I can say this for sure: it is extremely maddeningly difficult to write a song with my deliberative brain. When I bring my problem solving-solving brain to the table I also bring every cliché, standard phrase, and worn out idea I own, and they easily assert their primacy, to my disgust (p. 16).

I am sure we can all recall a time in our lives when music changed us in some way, helped us through a time of deep grief, or brought us joy. I’ve found a lot of solace in music with or without lyrics. Musically, artistic expression has always been something I hold close to my heart and one that seems to reach farther than any other medium of expression.

“Songs are frequently my teachers,” writes Peach, “I will later find in a song I’ve written a perspective or some information which guides my actions, as though in some way I knew what was coming down the river toward me without realizing it” (p.17). I was touched by this passage, knowing full well the impact music has had on me personally. This is what makes Questions to the Moon: Songs and Stories by Earle Peach so intriguing: the connection to your personal expressions and to what others are going through around you, to those you care for.

Peach also explains the musical aspects of his social activism. In 1984 he was working at the Carnegie Community Centre in Vancouver’s DTES (Downtown Eastside), an impoverished community where devastation continues, a place that needs our help, as Peach recalls. “In the DTES I saw people directly suffering from the disease of capitalism, and just a few leaders speaking up and fighting for them. The problems were overwhelming, and grew more so over time” (p. 44).

Many were aware of the ongoing and seemingly intractable problems in the DTES, and Peach’s solution involved setting up a musical outreach program:

I felt hopeless, especially because I was an outsider to it all, male, white, better educated and employed … of course my powerlessness didn’t remotely compare to what I saw those around me going through. The only answer I had, and have, to despair, is to create beauty in the face of it, so that’s what we did in the music program. It’s become a major part of what I see myself doing in the world … not just to create beauty if I can, but to facilitate others doing so as well (p. 45).

Peach’s activism is a reminder that we all could take another look at ourselves to see how we can contribute our own gifts to the wellbeing of the less fortunate in our communities.

*

Jeffrey Stychin has felt like a man out of time and in the wrong place ever since he noticed the town he grew up in, in the BC interior. He studied verse and poetry through music and art. He began writing as a means of catharsis and as a way to communicate with himself and others. A Vancouver barber by day, a poet by night, he currently resides with his thoughts and dreams in a quiet place full of trees. Editor’s note: Jeffrey Stychin has also reviewed books by Sonja Ahlers, Cole Pauls, Jeremy Stewart, and Brodie Ramin for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1652 The language of song”