1645 Ferlinghetti of the Shuswap

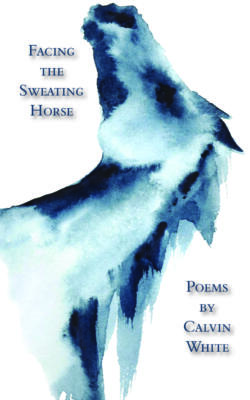

Facing the Sweating Horse

by Calvin White

Surrey: Now or Never Publishing, 2022

$19.95 / 9781989689424

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

Houses have views. They face them. Some face the street outside, or a garden, a fence, a city, a lake, a river or mountains. Some face fields and grasslands. Some face the sea. The world they face, and all people who don’t live in them, face them right back.

Houses have views. They face them. Some face the street outside, or a garden, a fence, a city, a lake, a river or mountains. Some face fields and grasslands. Some face the sea. The world they face, and all people who don’t live in them, face them right back.

That’s humbling. Houses are human dwellings, extensions of bodies, dreams, shelter and care. People live in them, are born, grow, suffer, eat, celebrate, make love, protect or torment each other, and die in houses.

Poems are human dwellings, too. For Calvin White, a former high school counsellor and volunteer with Médecins Sans Frontières, his view is of a world of pain and beauty, which are pretty hard to separate. Compassion, though, is possible, and togetherness with others, as well as simple language open to all. “The purpose of life,” Facing the Sweating Horse says, facing its potential readers head on, “is connection…The purpose of life is to recognize that connection.”

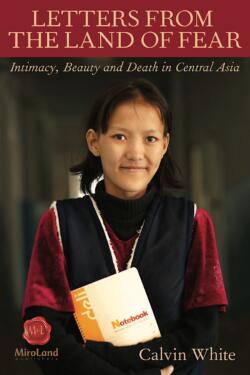

From a small town in the mountains of British Columbia, White actively seeks to connect with a vast world of people and their anguish, and the human touch that might heal it. That’s quite a role for Salmon Arm, a tourist town, to play, but White is no tourist. Faced with people facing death from TB in a culture with less faith in sophisticated antibiotics than in traditional medicine, he writes “I tell them they are not patients / but full human beings / I arrange for concerts so they can dance” (TB Numbers). [See White’s Letters from the Land of Fear (Guernica, 2015) — Ed.]. Masked and gowned, in a now-too-familiar image of PPE, “as the music blares,” he writes,

I hold them close for minutes not seconds

close your eyes

relax and breathe

I am giving you my energy

In doing so, he gives that energy to us. “There is a fear of being infected,” he continues, but adds “Life is like that.” It’s a neat dissection of life and death, through the simplest of human means.

This is the beauty of connection, not of description. One of White’s heroes is the great Czech poet and doctor Miroslav Holub, who continued to write poems as acts of surgery on the social body of his people during 40 years of communist rule. This work helped keep them compassionately alive all that time, because “in every voice / there is a uniqueness // like a child’s memory of darkness / or an old man’s memory of birth” (The Scalpel of Miroslav Holub).

White’s view includes his son’s struggles with crystal meth, scenes of domestic violence, poverty, plagues and misery of all kinds, all caressed the way you would comfort a horse with your hands. The horse is here, too, “a rearing horse in red / and a small Confederate Flag” (Open Late) — an image for Canada and the USA during the pandemic. White brings this story down to scale:

He is tweeting out what is happening

for the world to hear

his daughter only knows

too well

For White, children are simultaneously more aware than adults and in need of protection and guidance from them.

White extends this notion of difficult balance into the symbol of a sweating horse. He faces it — gives it a face, an appearance — and it gives him one back. As we are British Columbians, living in houses of imagery and information that both connect us and separate us from each other, it gives us a face as well. He is asking us to look out, and to look in, as one act connected through action.

With this image, White is honouring traditions. The sweating horse is an old image of art. W.B. Yeats, the great Irish poet, used it as a symbol of the power of poetry to change the world. His reference was the point of transformation of Ireland from a place of rural poverty and degradation to a land of beauty and romance and the freedom the change in consciousness enabled.

The sweating horse is also a Chinese symbol of beauty. Horses sweat for the reasons humans do: out of exertion, to cool themselves down, and out of fear and agitation. In Central Asia, where White volunteered as a mental health counsellor on a team combatting a drug-resistant strain of tuberculosis among once-wealthy horse people reduced to post-industrial poverty, the vital horse image is of a horse that sweats blood. Believing that the blood-sweating horses of the Fergana Valley were directly descended from the horses of Heaven, the Emperor Wu once sent an army of thousands to bring their power to the Imperial Court.

White’s view, as he writes in the title poem of Facing the Sweating Horse, is also one of Heaven, although in modern terms, it is the sky. “When a sky changes / and new clouds appear,” he writes in lush sexual imagery, there is a moment when hands can open from fists into fingers. Then, the fingers, these extensions of the mind that change distance into touch, start thrumming on skin. In that connection, in that desire for poetry to do something,

there is a moment

an open space

for the mind to kiss

pounding like hooves

This image of freedom is well-chosen. TB patients cough up blood. They have parasites in their blood that eventually steal their breath by eating their lungs away from within. Horses that sweat blood are riddled with parasites as well and collapse from it just as surely. In either case, a doctor, or a rider, must act, not talk.

The shape of White’s poems, and his gaze on the world, are just as deliberate. There is great beauty here, but not set down to extend art’s subtleties as Yeats did. It’s here for purposes of direct medical intervention. These are poems set down to be read aloud, body to body. If read that way, the poems leap off the page, each line individually calling out into silence like those pounding hooves. They make bodily connections.

An example of this method is the way White stretches out the spaces of his endings to slow us down from a gallop to a point of recognizing the separate identity and contribution of each single word (or footstep). One such poem is “Plum God,” which I both an honouring and repudiation of William Carlos Williams’ famous poem of desire “This is Just to Say” about stealing plums in the night that his wife had probably been saving for breakfast. Williams asks for forgiveness but ends with bitter shame and regret. Not so, White. For him,

on some

there are sticky bubbles of sap

each holding

the moon

The moon, holding, plums and attraction (well, stickiness) are all separate, yet also, together, instances of unity. You can have your masters, and extend them without losing yourself.

Personally, White extends the tradition of his own poetic master, the renowned American beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. You can set Ferlinghetti’s work side by side with White’s and read directly from one to the other. In “Not Like Dante”, after all, Ferlinghetti wrote (in 1958),

but there would be no anxious angels telling them

how heaven is

the perfect picture of

a monarchy

The pacing and the sense are the same. White’s poems and Ferlinghetti’s are one body.

Of a personal meeting with Ferlinghetti, White writes “The space between each word was like the space between great oils in a gallery set upon just the right wall, like the space in the bedroom breath when a newborn baby begins to wake” (A Monk’s Robes). That describes the work of both of them well.

We are blessed. We have suffered great loss and continue to suffer it. Our pandemics of violence, addiction and disease are knocking us about terribly and Ferlinghetti died in 2021. However, all is not all bleak. Ferlinghetti is alive here, for one, his work and poetics extended in Salmon Arm, a small town in British Columbia that is all the world, a gallery that is a book, this book, these poems, this house. “Paint your words each one as slow as ice on the page and with the same swing of Mehudin’s bow” (A Monk’s Robes), Ferlinghetti told White.

White has listened well. The work of hands continues: whether hands that heal, hands that hang pictures or drum out poems of touch on a lover’s skin. Instead of focusing on the destruction of death, White writes, “moving forward let us think of the better days ahead and / what we can learn from this” (Moving Forward).

*

Harold Rhenisch left the small BC town of Keremeos for Victoria in 1975, with Ferlinghetti’s The Coney Island of the Mind in his pocket, in the hope of continuing in Ferlinghetti’s footsteps. He found other masters, but is sure glad to come home to Ferlinghetti now. Rhenisch has written some thirty books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for The Wolves at Evelyn (Brindle & Glass, 2006), a memoir of German immigrant life from the Similkameen to the Bulkley valleys. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack (New Star, 1999) and Out of the Interior (Ronsdale, 1993). He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and has worked closely with the photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass (2008), Motherstone (2010), and Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2016), as well as on The Bowron Lakes (2006), all published by Country Lights; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. He is working on Commonage, a history of the Okanagan region, highlighting the American history of Father Charles Pandosy and situating the roots of the Commonage land claim in the North Okanagan in American colonial practice in Old Oregon. Harold lives in Vernon. Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has recently reviewed books by Garry Gottfriedson, Susan Smith-Josephy & Irene Bjerky, Bill Barlee, Fred Braches, Raphael Nowak, and Karl Koerber for The British Columbia Review. His recent book Landings (Burton House, 2021) was reviewed by Luanne Armstrong, and The Tree Whisperer (Gaspereau, 2021) was reviewed by Adrienne Fitzpatrick.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

11 comments on “1645 Ferlinghetti of the Shuswap”

Thanks Harold, well said! I have known Calvin White for 40 years yrs & his moral integrity has always astounded me. There is a lot of talk about spectrums these days. Calvin is on a spectrum: it just so happens that he is on the top end of the spectrum of empathy & human kindness! This comes out in spades reading Facing the Sweating Horse. Thank you.

What a fine review, Harold. You make it clear that Calvin White is a poet of great compassion and depth!