1646 Every day has its gold

Dancing in Small Spaces: One Couple’s Journey with Parkinson’s Disease and Lewy Body Dementia

by Leslie A. Davidson

Victoria: TouchWood Editions (Brindle & Glass), 2022

$22.00 / 9781990071089

Reviewed by Lee Reid

*

When married retired teachers are double diagnosed, he with dementia and she with Parkinson’s disease, there is not much space to dance. But dance they do! Despite life-altering changes and his move into an extended care residence in Revelstoke, they find their beat.

When married retired teachers are double diagnosed, he with dementia and she with Parkinson’s disease, there is not much space to dance. But dance they do! Despite life-altering changes and his move into an extended care residence in Revelstoke, they find their beat.

Dancing in Small Spaces is a love story about Leslie Davidson and Lincoln Ford, a couple who learn how to age creatively and keep connected, no matter how much life, disability and death challenge their love. The book, compiled and written by Leslie, chronicles their journey from double diagnosis in 2011 to Lincoln’s death in 2017, with subsequent glimpses into her changed identity as an elder woman alone. Theirs is a journey that demands resilience, courage, imagination, and the ability to rise to unusual challenges with humour. “Love in a Different Way” is an apt term for this resilience, coined not by Davidson but by an elder friend of mine whose husband died recently from dementia.

Leslie Davidson is a grandmother who lives in Revelstoke with her family. Until Dancing in Small Spaces, she had written children’s books. Leslie speaks and writes sincerely from her heart in a whimsical style that will touch people of any age, for example:

I see myself as an ancient crone, bent and addled, hand-sewing a crazy quilt of all the tattered scraps of our last years. I feather stitch together the bits and pieces of our stories, and I dream that when it is finished I will wrap it around all those who loved him. We will touch the pieces of ourselves that cling, thread by thread, to one another (p. 3).

In Dancing in Small Spaces Leslie frequently refers to herself as a “Parkie” (or “PWP … person with Parkinson’s disease”) after her diagnosis in 2011. In the same year, her husband Lincoln was diagnosed with Lewy Body dementia. Leslie’s book chronicles the couple’s next six years together, navigating cognitive and physical decline. “The thing about the middle of the night,” she writes, “is that grief grows large, larger, largest, in waves and stabs and shifts. It dances with anxiety, and that is one hell of an unsettling, hobbling two-step” (p. 200).

As their symptoms progress and mobility and cognition break down, the couple find themselves undergoing “the long goodbye.” Although the term “slow quitting” is a technology term that refers to aging computers, I find it applicable to “the long goodbye” as the person with dementia gradually disappears from engaging. The resulting book, which Leslie began in 2018 when she was awarded a writer’s immersion at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, is heartbreaking and beautiful. She asks, “Where do they go, these shattered bits of you and me?” (p. 2).

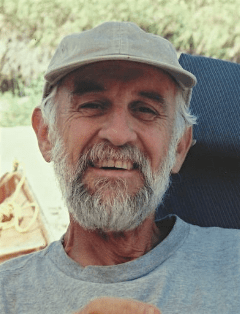

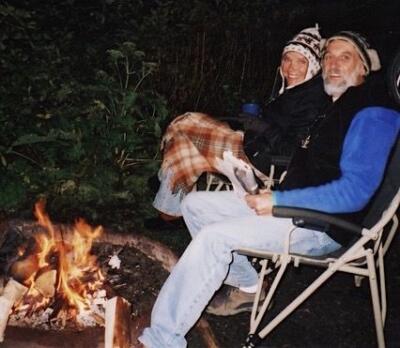

Davidson dedicates the book in honour of her family and her husband. Her collection of stories, including her children’s books, celebrate nature and heartfelt human connections. With Dancing in Small Spaces, her hope and intention is that the poignant stories will inform, support, and help readers whether or not they have dementia or are seniors. She grieves that new friends and future community will never know her husband Lincoln, who transforms in the book from a risk-taking adventurous mountain climber (“a force of nature”) to become a quiet and frail beloved old man slumped in a wheelchair. Readers might experience this older immobilised Lincoln as a silent and lovable presence who, with Leslie, shapes their “tattered scraps” of life into wisdom that they will learn from.

Readers will learn about accepting help as Leslie and Lincoln must do. With Leslie, readers learn how to diminish the guilt that accompanies horrifying decisions that feel like a betrayal, such as placing her husband in care. Readers learn how she comforts and reassures his reaction that he is abandoned, and nobody wants him. “What I wish for myself, I wish for all of us — words that comfort, hope that guides and love to hold us in its gaze” (p. 205). Seasons pass as she collects photos, writes, and archives records of their conversations. “Outside the snow falls in straight lines like white rain” (p. 179). Nature, like Lincoln, is a constant presence and inspiration throughout the book. Nature brings solace and coherence to balance the chaos of life unravelling.

In 2016, Leslie was invited to the World Parkinson’s congress in Portland, Oregon. From this she joins a community of Parkies who comprise some of her support network. While she reaches out for resources to help them, her husband undergoes night terrors and delusions. He hallucinates invisible people who sometimes threaten him, and he struggles to recognise the real Leslie as his wife. Leslie must be ingenious, employing quick wit to create safety measures for him. She speaks to the delusions directly as if the imaginary people were real, ordering them to back off or come along for hikes with her and Lincoln. She buys a black toilet seat to reduce Lincoln’s visual distortions and subsequent terror of the bathroom. When he fears that she has a doppelganger or a nasty evil double, she pretends with him that there are two wife Leslies. One is good, an ally, and one is mean. She disguises herself as the friendly Leslie and pivots to engage the shifting perceptions that command Lincoln’s reality. “Every day a hundred small confusions and every day they change” (p. 81).

She compares their marriage to a canoe trip. “We did not always paddle in the same direction. We often worked at cross purposes but always managed to stay in the canoe … it makes me laugh and then it makes me cry.” And she continues:

[We] hit a rough patch and treat each other badly but carry on because we have so much work invested in staying together. And we love each other. After a few rough days we apologize and return to a place of calm waters and easy paddling, with just enough excitement to keep things interesting. I love metaphors and am good at stretching them. I think this one works for us (pp. 83-84).

Excerpted from Dancing in Small Spaces is her prizewinning story “Adaptation” about diverting their evil double while on a riverside walk with a panicked Lincoln. The story was published and won the 2016 CBC Creative Nonfiction Prize, which enabled her to begin writing her book at Banff.

This is a significant book for these 21st century times when the burgeoning baby boomer population is most vulnerable to age-related health issues such as dementia or Parkinson’s disease, topics that are still avoided as embarrassing or shameful in social conversations with what a friend of Leslie’s humorously and Potterishly calls “muggles,” or apparently normal people. Both conditions can seriously alter mobility and cognition and speech, and Parkinson’s can result in dementia. I felt thankful that at least Leslie and Lincoln did not have to endure the years of COVID-19 isolation while Lincoln was in care. Their antidote to cultural unease? “We make the choice to be as open about Lincoln’s illness as we have been about mine, to not close ourselves off or pretend all is right with our world,” Leslie writes (p. 46). While Lincoln was alive, they were able to normalise their situation, were included in social gatherings, and made new friends.

Dancing in Small Spaces addresses some gaps in the health care system that affect the couple, and for readers it might raise more questions about the “big picture dilemmas” in health care that we see highlighted in the daily news.

Questions about seniors’ care are at the core of this book. Who will take care of (or house) people with dementia like Lincoln, or even Leslie if Parkinson’s seriously impairs her functioning? Waitlists for placement in long-term or extended care are enormous. Currently, the demand for extended care facilities and for affordable housing outstrips the services available. Who will care for the fragile when home-care nursing and subsidised home visit and meal delivery services have been cut? When people can’t get a family doctor? When many overwhelmed families can’t or won’t provide the care? Or when ailing seniors line the halls of hospitals because they have nowhere to go?

In Canada, according to statistics on the Health Canada website, one in four people over the age of 80 develop dementia. The numbers are expected to double in ten years. One in five Canadians have personal experience tending to a person with dementia, and 450,000 Canadians (possibly as high as 500,000 by 2024) contend with mild cognitive impairment but remain living independently. Leslie finds herself inhabiting or skirting both groups as a caregiver with a handicap. The couple’s fathers and Leslie’s mother died from relevant dementias. “Sorrow is a constant in my story, as it is in so many people’s stories,” she reflects (p. 173)

“I want to go home,” laments Lincoln at times when frustrated or sad, as does Leslie — a natural reaction to continually losing their grounding in the familiar connections that anchored their married life of fifty years together. Of the two, Lincoln was more the risk-taking playful optimist, and a loving grandfather. Leslie characterises herself as the more anxious attentive spouse prepared for the worst, but she has a whimsical and wicked sense of humour and learns superpowers to turn disasters into breakthroughs. She also has a writer’s ingenuity for translating mundane details about daily life into “aha! moments” of discovery, magic, and absurdity, thus enabling the couple to meet new challenges with humour and love. The couple’s dreaded double diagnoses force them to redefine new paths home to each other.

Dancing in Small Spaces is rich with the skills they learn to manage unfathomable stress. This book could not be more timely. Culturally, the past five years have exploded in global conflicts and climate-related economic, health, and political crises. Uppermost for many, and seniors in particular, is loneliness and terror of the unknown. Aging, or illness at any age, can herald the loss of friends and loved ones, as Leslie reveals:

I am now on my own, alone in a way I have never been before …. Now I am forced into an independence I never wanted and if I am honest, it frightens me. Feeling guilty may be a whole lot easier than plumbing the depths of sadness that clearing out the stuff of our lives evokes in me (p. 133).

I am grateful for models and mentors with aging like Leslie and Lincoln — grateful for courageous people who provide intimate educational models of resourceful people growing through trauma and disability. Dancing in Small Spaces offers a tender example of compassion deepening through crises and grief.

There are related examples. A year ago, I reviewed Four Umbrellas: A Couple’s Journey into Young-Onset Alzheimer’s,[1] a similar ground-breaking book written by Vancouver couple June Hutton and Tony Wanless (Dundurn Press, 2020). They were affected for years by Tony’s early-onset Alzheimer’s before they finally got the dreaded diagnosis. Both their book and Leslie’s are love stories that provide encouragement, advocacy, hope, and skills to readers who are struggling, or who want to educate themselves about the traumatic aspects of life, aging, and managing their health care. What is clear from these books is that dementia and negotiating with health systems can cause traumas in relating and in communicating. What remains unknown is if trauma (for example in early life) is a cause of dementia or other health issues later in life. Trauma specialists like Vancouver’s Dr Gabor Maté assert that it is.[2]

“Writing is a healing outlet for expression of pain,” to paraphrase Leslie in a 2017 podcast on her website. A large and growing number of online education programs teach skills with the many facets of trauma, offering practical wisdom from a seasoned pool of international therapists, teachers, writers, gerontologists, scientists, and health specialists. Whether or not she intended to, Leslie does a superb job of translating the trajectory and resilience demanded by trauma while it transforms her marriage. Her writing is enchanting, enhanced by the attitude of gratitude that she cultivates throughout:

No they don’t know what I am going through any more than I am privy to the hard truths of their lives. And so I don’t shout. I dig into that tangle of emotions and I find, along with the anger and the regret, the grief and the guilt, a bright thread of gratitude. I cling to that. I have that choice (p.134).

She faces handicaps that are painfully daunting, but she is also able to resource from the mountain and lake beauty that reflects the appeal of rural communities. That she and her husband were experienced hikers, canoers, kayakers, skiers, and travellers enhances the authenticity of her writing and the sensitivity of her perceptions: “I know things like this happen in other communities, but our kind bus-driving friends make me very grateful for my small town. Every day — no matter how bleak — every day seems to have its measure of goodness. Every day has its gold,” she reflects (p. 113).

What touches me deeply in Dancing in Small Spaces are Leslie’s accounts of the emotional learnings, vulnerable conversations, tough decisions, and inner reflections she faced with Lincoln. “This is the hard part, acknowledging my limitations, and it isn’t just about having Parkinson’s. It is about feeling that I have failed him again” (p. 187). The inability to recall or process information, or to solve problems, is an inexplicable and frightening unknown that grows painfully clearer as dementia progresses. And progress it inexorably does, causing paralysis followed by death for Lincoln. “I don’t know how he bears it but he does, with the grace with which he bears all the other indignities of his illness,” she writes (p. 162).

No, the author does not complain about the health care system, but she questions if the lack of stimulation maintained in care facilities could exacerbate her husband’s symptoms. She arranges with facility staff for a tandem bike called the Duet Tricycle to provide rides and some familiar outdoors excitement for him. Lincoln can then reclaim his joy in speed, freedom, and wind in his face, and she can pedal their “cool wheels.” Unless patients are resourceful caregivers like Leslie, they run out of time and yes, patience.

How do people manage disability? Sick or stable, they become frustrated, brave, funny, fearful, or anguished. They laugh, they get lost, they cry, they retreat from contact. Tenderness and pain may deepen, and people are stretched to communicate in ways beyond familiar. As Leslie’s Parkinson’s condition becomes more debilitating, she is forced to buy a new car so she can continue to drive. The couple must sell their home in Grand Forks and move to Revelstoke where there is more family support and an extended care facility, Mt. Cartier Court, with a waitlist. Leslie must make painful decisions about placing her husband in a day program and then in the facility. Without the generous help of their adult children and intimate friends, life and health care would have been far more traumatic. The book reveals just how involved families and grandchildren can (or must) get with their seniors when the elders are forced to live in care or alone.

Sadly, unlike Leslie, many families don’t get involved, or if they do, the caregiving often devolves to the women. Leslie’s descriptions of their grandchildren joyfully visiting their grandfather in his facility after school, or the loving care and kindness provided by staff and in-laws to help out when she has her own medical appointments, seems almost shocking to read about in this era, when many families live at a distance from their elders. And so we have a new term (not from Leslie’s book) to describe them: “elder orphan.” To be alone, really alone, after 30 to 50 years together is a shock. Leslie and Lincoln generate a remarkable community of friends and family who help them, offering respite care, walks and visits, conveyance to appointments, solace, and comfort.

How critically important community is for healing is an ongoing theme that will not escape readers of Dancing in Small Spaces. Rural communities are now more challenged than ever to fill gaps in care once provided by the health system. This can burden families already in pain. Nonetheless, the many tragic pieces of Leslie and Lincoln’s journey are threaded with absurd-to-terrifying moments as well as myriad joys. They discover that simple skills like dancing and hiking can become exercise strategies to reduce the anxiety that accompanies Parkinson’s and dementia. Leslie describes it as “Not lost, just going in one direction.”

The couple’s married daughters and their spouses, and their friends, provide invaluable support. There are the aforementioned endless waits, but community friends offer housing. There are the life passages we might expect with aging, such as the deaths of friends, parents, or siblings, or births of grandchildren. There is moving to a new home throughout a winter of hazardous Kootenay mountain passes. What the reader will appreciate is how Leslie and Lincoln communicate and manage the goodbyes: the letting go. All while navigating their symptoms and medications, battling fear, and trying to make sense of the incomprehensible changes in Lincoln’s brain and speech. Leslie loses her sense of smell and ability to sleep. Her sister suggests a simple language skill. By changing anxious “if” sentences” to “when” sentences, she successfully reduces her fear. “If we ever get to Revelstoke…” becomes “When we get to Revelstoke…” (p. 143).

What did seem slightly awkward to me in the book were the time-travel flashbacks to memories of earlier years. Although it is important to convey to readers the character and values of the couple, especially of Lincoln, at times I found it difficult to suspend present time when I was completely immersed in their journey through dementia. I could also understand Leslie’s intention to represent her husband with love and integrity, which she does through the artfully placed flashbacks, conversations, photos, and vignettes of their interactions and travels. Lincoln climbs Mount Kilimanjaro. Leslie writes and teaches. Her book is practical as she narrates the strategies and human networks she turns to for help. Writing helps her to heal: “And maybe, I tell myself, maybe I can write my way home” (p. 59).

Dancing in Small Spaces will inspire readers to trust that quality of life and love is possible after diagnosis and disability. Leslie ensures that Lincoln lives and speaks through her book. “Maybe one day you will read these tales,” she writes, “and get to know the grandfather in the red canoe, the soft-spoken adventurer whose courage and grace at his life’s end remain his most profound legacy” (p. 226).

*

A retired clinician formerly with Nelson Mental Health, Lee Reid has written four books about BC rural and coastal communities. Her stories centre around the values and health care needs of BC seniors. Lee has also written stories about intergenerational education, rural home support care services, trauma, and dementia. Recently, she has written and self-published a fourth book about the multicultural workers and residents who populated an historic extended care hospital in Nelson: Stories of Mount Saint Francis Hospital: 1950-2005, which illustrates a legacy of compassionate nursing care. She has also written articles and reviews featuring intergenerational education, rural home support care services, and the health challenges faced by rural BC seniors. Her books are: From a Coastal Kitchen (Hancock House, 1980); Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders (Nelson, 2016), reviewed by Duff Sutherland, and Growing Together: Conversations with Seniors and Youth (Nelson, 2018), reviewed by Luanne Armstrong. A fourth book was self published in 2021, Stories of Mount Saint Francis Hospital: 1950-2005, about the workers and the residents who populated an historic extended care hospital in Nelson. Visit her website here. Editor’s note: Lee Reid has recently reviewed books by Phyllis Dyson, Joan Neehall, Janie Brown, June Hutton & Tony Wanless, Megan J. Davies & Rachel Barken, and Ellen Burt for The British Columbia Review. In 2018 she contributed a popular memoir of growing up in the south of England and North Saanich, The Spider Hunters.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

References:

Canadian Institute for Health Information. This site is an excellent source of information about the effect of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease on Canadians.

[1] Four Umbrellas: A Couple’s Journey into Young-Onset Alzheimer’s, by June Hutton and Tony Wanless. Dundurn Books, 2020.

[2] The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture, by Gabor Maté, M.D. with Daniel Maté. Ebury Publishing, 2022.

4 comments on “1646 Every day has its gold”