1647 Hugh Greer’s career

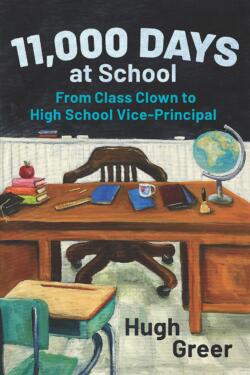

11,000 Days at School: From Class Clown to High School Vice-Principal

by Hugh Greer

Vancouver: Granville Island Publishing, 2022

$22.95 / 9781989467541

Reviewed by Bill Engleson

*

There are moments that just seem well-timed. This was one of them. It was a Sunday morning. I had several issues on the go and was avoiding most of them. After coffee, I responded to an e-mail request from a Comox Valley Writers Society friend, and in a serendipitous matter of leap-frogging e-minutes, Richard Mackie offered me the opportunity to review Hugh Greer’s memoir, 11,000 Days at School: From Class Clown to High School Vice-Principal.

There are moments that just seem well-timed. This was one of them. It was a Sunday morning. I had several issues on the go and was avoiding most of them. After coffee, I responded to an e-mail request from a Comox Valley Writers Society friend, and in a serendipitous matter of leap-frogging e-minutes, Richard Mackie offered me the opportunity to review Hugh Greer’s memoir, 11,000 Days at School: From Class Clown to High School Vice-Principal.

By happenstance, my most recent frolicsome Facebook post — from two days earlier after cyber-stumbling upon an ancient Nanaimo Daily News story — led off with this:

BREAKING NEWS. You’ll be happy to know that I was most fortunate, as of this news item from July 6, 1956, to be promoted from Grade 4 to Grade 5 at Brechin School. And I was but one of many to move on that year. It came as a surprise to my parents….

Evidently I was primed for a deep dive into the British Columbia public education system thanks to the subsequent arrival of Hugh Greer’s book.

Perhaps it was the kindergarten’s moniker, or some genetic predisposition or position in the family — Greer was an only child until his sister arrived when he was twelve — but from the get-go, he embraced his self-described persona of class clown. Television provided his mentors and role models, and early on he acknowledges those small screen wags: “My TV heroes were Red Skelton, Jackie Gleason, and, of course, the brilliant Three Stooges. I wanted to be just like them.”

To demonstrate the lengths he would go to emulate his exemplars, Greer regales us with a Grade 3 antic. “Did you know that if you carefully insert a pencil up each nostril, stick out your front teeth and clap your hands in front of you, you will look exactly like a walrus?”

Each of us might well want to consider a response to the pencil-in-our-nostrils-walrus question posed by Greer. I, for one, did know that one could immediately morph into a walrus by that means.

Shortly after the nasally walrus yarn, Greer shifts into pathos by contrasting how educators dealt with tragedy back in the day, and how tragic events are more carefully managed in the here and now. Throughout his data-crammed chronicle, he offers useful contrasts, the good and the bad, the yin and the yang. He rarely lets a page or two pass without injecting nuggets of school vaudevillian theatre to spare the reader the ache of relentless educational anguish.

In Grade 7, Greer moved to a new school, Seaforth Elementary, conveniently located near a television station, CHAN-TV — currently Global TV. His summary of visits to the studio to watch and participate in programming — principally Children’s Carrousel, hosted by the late impresario-of-all-trades, Ron Morrier, who was also the face of All-Star Wrestling for years — is full of Leave It To Beaver-like delights.

I should note here that Greer’s move to Seaforth also meant that for the first time in his scholastic odyssey, his parents, much like Elvis, had left the building. From Grade 1 through 6, his mother was his school’s secretary. When he progressed to Cariboo Hill Junior High in Burnaby for Grade 8 a year later, his father was the school custodian. By Greer’s own account, these parental proximities occasionally proved awkward for family congeniality.

Greer attended Burnaby Central for his final high school slog. By his own candid revelation, he was lucky to escape Grade 12 with an unembellished ticket to university. One teacher passed him in her subject on the condition that he not take her class the following year. He succeeded in another course, History 12, “by adjudication.” When the provincial History 12 final exam had been marked, he discloses, “too many students had failed, so the Ministry of Education markers marked them all again and lowered the standard to pass.”

In 1968, Greer was accepted at the University of British Columbia. His career aspiration at the time was to become a P.E. teacher. Interestingly, he makes no mention of Simon Fraser University, the relatively new university much closer to home. Quite possibly the reputation for political activism of that campus was a tad off-putting for Greer or his parents? Later he offers a coaching vignette that involved an unpleasant incident at a school basketball tournament at Templeton High School in East Vancouver. Templeton played a pivotal role in the emergence of SFU as a lightning rod of student militancy in the late sixties. Again, nary a whit of a reference.

In any case, he zoomed through first year at UBC — a university not without its own modest student political storm swirling, though none of this is even hinted at by Greer — only mildly scathed, and proceeded through the next four years of teacher education with the aplomb of a young soldier preparing for war. Not having been a high school jock, for example, I was unaware of the menacing dangers of P.E. classes. Greer leaves the impression in a couple of his parables that high school gyms were not all that safe.

Nor were staff rooms, apparently. Unlike the staff room in the classic 1955 film, Blackboard Jungle, which, for all that school’s assorted challenges, permitted male and female teachers to break bread together, Greer reports that the staff room at Eric Hamber School — where he did his fourth year practicum and later secured his first teaching gig — “was segregated by gender in 1972 and was not a place that welcomed female members of staff.”

There is an ingenuous honesty in Greer’s rendering of his professional teaching years. This is painfully evident in his revelation that a little over a year into paid teaching, at the age of twenty-four, he reported a student to the VP at Eric Hamber for intoxication. Later, the mother demanded an explanation as to why her daughter was singled out, pointedly asking, “Is it possible you singled her out because you are antisemitic, Mr. Greer?” Greer had been instructed to hold his tongue but failed that directive, a condition he admits elsewhere lasted throughout his career, and replied, “I’m sorry but I don’t know what that word means.”

I confess that I found that admission shocking. I have three years on Greer, but I have little doubt that I knew what antisemitism was from a much earlier age. Surely the vileness of antisemitism was one of the significant lessons burned into our being from the Second World War?

After a couple of years of teaching, Greer took a year off to travel the world. While he pretty much covers that adventure in less than a page, I suspect he may have another book in him. That aside, he returned to Vancouver and slowly climbed the educational corporate ladder.

The balance of 11,000 Days illuminates Greer’s decades of service within the Vancouver School system. In epigrammatic, easily accessible colloquial sketches, some augmented with sunshine, others darker and vaguely disturbing, he illustrates the world in which he found himself. Always self-deprecating, almost to a fault, he notes at the end of his career that, ”The first day I walked into the Tinkerbell Cooperative Kindergarten, I was five years old and knew absolutely nothing about anything. Fifty-five years later, … I walked out of my last school and knew a little bit about a few things.”

A quibble. In a memoir, it’s probably unnecessary to say, “This is my story, anyway, and I’m sticking to it” more than once. And maybe even once is pushing it.

A final thought. In my previous life as a social worker, I had the privilege and obligation to attend at many schools. I would arrive, touch base with staff, both teachers and administrators, be offered a quick summary of the child’s (or children’s) life as it was known to staff, and then conduct an interview. Missing in much of that process was a sense of the complexity existing in every school. Greer, in his highly personalized way, offers a vivid lens into school hierarchy, internal and community politics, and areas of real (and imaginary) concerns that befuddle and flummox educators. I have to thank him for that edification.

A bonus final thought. Greer spends considerable time offering what I assume is an accurate portrait of his parents. Though he cites his own immediate family early on — a grandson’s learning curve in kindergarten, or the year that he, his wife, and two young daughters lived in England on a teaching exchange — a family member does not make a significant appearance until much later on (p. 214), when suddenly his older daughter is about to transfer to the school where Greer is Vice-Principal. I was surprised that that he spends no time examining that situation, a state of affairs not unlike his angst-laden formative years when he was a student surrounded by microscopic parental surveillance.

A bonus final thought. Greer spends considerable time offering what I assume is an accurate portrait of his parents. Though he cites his own immediate family early on — a grandson’s learning curve in kindergarten, or the year that he, his wife, and two young daughters lived in England on a teaching exchange — a family member does not make a significant appearance until much later on (p. 214), when suddenly his older daughter is about to transfer to the school where Greer is Vice-Principal. I was surprised that that he spends no time examining that situation, a state of affairs not unlike his angst-laden formative years when he was a student surrounded by microscopic parental surveillance.

A truly final thought. When I first saw the title of Greer’s memoir, my first brainwave, being a cinephile, was that he had metaphorically reconfigured the classic 1932 Spencer Tracy prison film, 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (which I suppose dates me).

Probably I was mistaken.

*

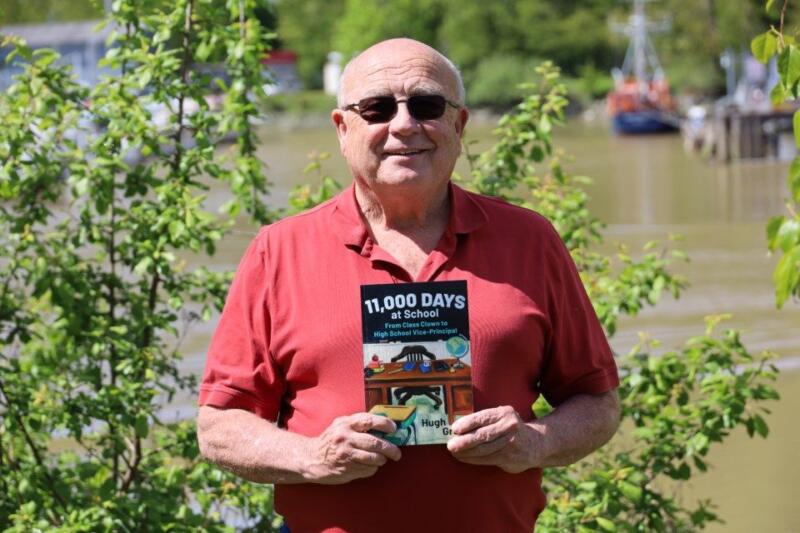

Bill Engleson is an author and retired child protection social worker. He was born in Powell River, raised in Nanaimo, and spent his first year of life trapped aboard his parents’ leaky fish boat. He resided in New Westminster for most of his adult years, retiring to Denman Island in 2004. He writes fiction, essays, poetry, and letters to the editor. He has been writing most of his life and his first couple of poetic efforts were printed in his mid-teens in the, now, sadly defunct Nanaimo Daily Free Press. He self-published his first novel, Like a Child to Home in 2013. Silver Bow Publishing released his second book, a collection of humorous literary essays titled Confessions of an Inadvertently Gentrifying Soul, in October 2016. He is working on several projects including a prequel to his first novel, Drawn Towards the Sun, and a long simmering mystery, A Short Rope on a Nasty Night. While many of his longer projects are taking their own good time, his story, Fidelity, recently took second place in Geist’s short long-distance writing contest and he is poised (he often uses the word, poised) to publish his latest novel, The Life of Gronsky. Visit his website-blog here. Editor’s note: Bill Engleson has reviewed books by Daniel Wood, Luke Whittall, JG Toews, Jack Knox (Opportunity Knox), Jack Knox (Hard Knox), and Mike McCardell for The British Columbia Review. He has also contributed an essay on Drinkwater Library on Denman Island.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1647 Hugh Greer’s career”