1169 Dying with love and compassion

Radical Acts of Love: How we find hope at the end of life

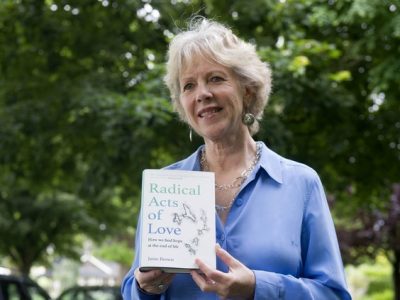

by Janie Brown

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Anchor Canada), 2021

$22.00 / 9780385694759

Reviewed by Lee Reid

*

The Cree woman invites her friend to share a covenant: “There comes a time, she said, when the elders must release those stories into the world.” Referring to Janie Brown’s years of experience as an oncology nurse and counsellor, the woman extends an invitation: “You have many teaching stories by now, don’t you? …I believe the time for releasing these stories is now” (p. xxii).

The Cree woman invites her friend to share a covenant: “There comes a time, she said, when the elders must release those stories into the world.” Referring to Janie Brown’s years of experience as an oncology nurse and counsellor, the woman extends an invitation: “You have many teaching stories by now, don’t you? …I believe the time for releasing these stories is now” (p. xxii).

In the introduction to her book Radical Acts of Love, Janie Brown, co-founder and executive director of the Callanish Society in Vancouver, explains her intention: “Preparing for death is a radical act of love for ourselves, and for those close to us who live on after we’re gone…. This book is my contribution to the re-empowering of all of us to take charge of our lives and our deaths, remembering that we know how to die, just as we knew how to come into the world” (p. xiii).

Writing with lucid and warm conversational style, Janie narrates twenty stories collected and collated from her years of interaction with patients, friends, colleagues or family whose lives have been affected by cancer. Whether or not readers will personally relate to cancer, these stories do hold potential to soften the isolation and fear associated with disease or with any potentially life-changing event. As well, the stories are illuminating and instructive for medical professionals and students, and people who work in palliative care. When Janie mentions, “I am proud to work with such compassionate people who show me every day that the most powerful medicine in the world comes from the heart,” it is clear that this could very well be a medicine book (p. 281).

She outlines several key themes in the book. The themes evolve through poignant conversations with people about “opening to death, preparing for dying, healing the past, dealing with unfinished business or accepting what is unresolved, making choices about dying on one’s own terms, and learning to draw comfort from nature and the universality of death” (p. xxi). All stories conceal the identities and confidentiality of the people involved.

Tears may well up for readers, as they did for me, although this is not a depressing or overly clinical book. The people and stories are vulnerable and human. Janie states: “My wish is for this book to inspire hope in families who want to live and love as best they can in the period of time between learning of a poor prognosis, and moment of death itself” (p. xxi). Although the stories centre around peoples’ journeys with cancer, Janie brings consistent and sensitive witnessing to each. “The people I met lived inside me and I carried them around with me as I went about my life. It felt like I was keeping them company” (p. 119).

“Opening the Heart To Dying” titles the first section of five stories. Janie asks Dan, who is dying, “What do you miss most about yourself?” (p. 66). This is a sensitive question that may sound harsh or judgmental to readers who define life through their productivity or who still trust they can control the present and the future. Instead, the question actually invites a sharing of cherished memories, fears, grief, and acceptance for people who must let go of “normal.” In that process, Janie describes a healing space that opens in conversations: “…this connection through suffering can create a feeling of spaciousness or wholeness that I believe is the potential healing space. I found that if I mostly listened and spoke rarely, Dan talked himself through his feelings until he finally ran out of words…and a deep quiet wrapped around us” (p. xvi).

From stories such as Daniel’s, I learned that hope is not about controlling death or imposing strategies to battle disease. Patients, friends and loved ones die in the book. Although Janie’s responses and her moral dilemmas with ethical care are transparent, her communication and role focuses on supporting what is essential and healing in the people. The intense grief of those who face inevitable loss or loneliness in the stories is palpable, yet the overall effect on readers is of compassion, acceptance, and shared humanity. “Preparing for death is a radical act of love for ourselves, and for those close to us who live on after we’re gone” (Janie, p. xxii).

Readers will discover how, and why, hope arises from emotional engagement with others. Many stories, and Janie herself, illustrate a process of empathic inquiry and of listening. Readers will learn how this restores people’s connections to themselves and each other. In Janie’s words, “… sadness, regret, anger, disappointment, self-blame, guilt, envy, love, peace and many others…to have the courage to open our hearts to our feelings offers us the possibility for deep healing before we die” (p. 129).

In the section titled: “Accepting The Unresolved Heart,” four stories describe the complexity of human relationships, decisions, ethics and moral distress in relation to dying. Janie is very honest about her work as a nurse: “Standing up for what we believe in is the daily practice of oncology nurses, but I had yet to learn how to do that and keep my heart open” (p. xviii). As a caring professional who is openly dissatisfied with the roles and gaps in health care, (gaps that may magnify fear and loneliness for patients), she turns to integrative medicine in her career. Integrative medicine focuses on health of the whole person (body, mind, spirit) and addresses lifestyle. Radical Acts reflects this approach to health care.

The uniting theme for me is compassionate presence. Stories in Radical Acts model willingness to walk through the darkest of times with people. It’s a vulnerable process that encourages hope, and breaks down barriers in relationships as well as traditional roles in health care that objectify the patient and the health professionals.

With one terminally ill patient, Janie comments: “It was like an excruciating softness had fallen upon us. I felt a deep quiet inside, inexplicably at home in the presence of a man grappling with an unfathomable situation” (p. 118). Connections such as this are honest, if not heart wrenching, and they give patients and readers permission. It is a rare permission that suggests hope or even wholeness is possible when people share overwhelming pain, anger, or terror.

Patients in Radical Acts wrestle with dilemmas that are fraught with complex moral and ethical choices. Their experiences may be relevant for readers. Janie describes the process as, “the work people wish to do: to grieve the unattended sorrows of a lifetime; to rage against past hurts; to try to forgive oneself or others, or at least to accept what has happened; to settle fears and worries; to say goodbye to family and friends; and to leave a legacy” (p. 129).

For readers like me, who certainly have fears regarding cancer, the book is reassuring. Janie’s approach is to lean into, and name, the tough issues. This creates safety. “Accepting our loved ones will die opens us to life’s impermanence, and to our aloneness” (p. 124). The stories illustrate fears common to people affected by a cancer diagnosis. Some examples that occur to me would be: “Would cancer or disability consume my life with painful treatments? Will I be disfigured, ugly, or dependent? Will I be a drain on family and lose my friends? Will the doctors abandon me if the cures don’t work? Can I trust the medical system?”

Readers may feel urgency with, and for, the people in the stories who want to resolve or complete their lives before they die. In fact, this urgency might not be a race against death. Often, people with cancer have no time to waste on superficial talk. Most are clear that they need their lives, and what was unresolved in their lives, to be named, felt, and witnessed. Some are very adamant that they need to clear up past traumas and regrets. Conversely, others refuse to accept dying, or are “too busy for cancer.”

In the section on “Healing the Troubled Heart,” readers share Janie’s inner dilemma about confronting a wife who refuses to accept her husband’s impending death. The wife overrides his wishes to forego more treatment: “I wish I’d had enough experience in those early days of my career to step towards Janet, to touch her arm, to look softly and directly into her eyes and ask directly if she was frightened of what was happening to George, to her life” (p. 121). What readers will learn from such stories is how to get underneath conflict and anger to form a connection; how to engage people through their darkest passages.

\One example of hope and healing is Bella, who works hard to release emotions and rage buried in her body from the toxic abuse she suffered as a child. “I am ready to go,” announces Bella at a Callanish retreat. “All my soul searching has paid off,… My unfinished business is done … I feel like I retrieved the parts of myself that went missing long ago, thanks to all of you, and the hole filled in. I wish I’d known how to do that years ago, but at least it happened before I died holey” (p. 146).

A caution for Ormsby readers: do not become trapped in negative preconceptions about cancer, or assume that all cancer stories are the same. Janie advises, “Early on in relationships with clients, I search for core strengths … Did they feel loved? If not, has their sense of self been diminished or strengthened by life’s challenges?” (p. 46). I recommend that readers treat the stories with similar regard and an open mind.

Do our bodies know how to die? This suggestion, posed in the introduction to Radical Acts, is the conundrum that probably occurs to many readers. Unless faced with our mortality, we might prefer to ignore it. When we vicariously sit with Janie at a patient’s side, and the dying person or loved one asks, “what lies ahead?” or, “what should I tell the kids?” or, “should the kids be here when I die?” their questions invite deeper self reflection in readers and more willingness to explore the unknowns of dying.

“What will dying feel like?” asks a patient.

Janie describes the physical process: “We live up until the last breath, really, but there is a time when we enter the final phase of dying which usually lasts from a few hours to a few days. The body doesn’t want food or liquids anymore, and the organs naturally shut down. You’ll be asleep more than awake, and you will likely know you are dying” (p. 23). In another passage, she describes the final changes in breathing before death. For me, this was reassuring. I have sat with dying friends, but I lacked any background in nursing or palliative care to guide me. If I had the guidance of Radical Acts, I would have felt more confidence, more ability to be quietly present, more faith in the body’s innate wisdom to die and let go when ready.

Radical Acts does not dwell on settling estates and wills, signing off on medical procedures, assigning power of attorney, planning funerals, and the legalities of life ending. For me, it was a relief that such logistics were mentioned but did not command the stories. I preferred to hear how patients left memories and tributes to their loved ones, or how they came to terms with their past history. In their time remaining, what did they understand about legacy, or about end-of life-celebrations before or after death?

When some of Janie’s patients chose to tape caring messages to loved ones, to leave as a legacy, I felt deeply moved and oddly hopeful. Grief infuses the stories, yet equally there is empathy to support their understanding of a greater reality that Janie calls “the spacious heart.” As people in the stories sort through cherished memorabilia that they wish to be passed on, or plan end-of-life ceremony, the process creates hope and love mingled with sadness.

Was it intentional that their stories and questions offer readers the opportunity to reconcile with aspects of one’s own unresolved history? Although this may be an uncomfortable process, do pay attention! It is one of the gifts of this book.

“This is not my fault is it, Janie, getting cancer?” asks a patient.

Janie responds with characteristic honesty: “Of course it’s not your fault,” … with a vehemence that surprised me … If you can find compassion for yourself, Daniel, then your daughters will learn from you. Your dignity and self-respect will accompany them throughout their lives” (p. 25). In conversations such as with Daniel, we begin to comprehend what ‘radical acts of love’ means.

What does Radical Acts mean for nursing?

Some stories express mistrust, or terror, not only about dying, but about cancer treatment and cancer care. People fear medical interventions; they fear being objectified and abandoned by health professionals when they are vulnerable. This compelled me to ask, ‘How can nurses respond to their patients’ vulnerability and fears? Is it possible for health professionals to bring an open heart to oncology, especially in busy hospital settings or cancer treatment clinics?’ One rebellious and mistrustful patient in the book exclaims, “I’m more scared of being kept alive than of dying!” (p. 9).

Readers will discover that it is possible (albeit challenging) for empathic medical presence to weave throughout the myriad tasks of patient care, particularly when deeper inquiry and connections are valued by professionals. Radical Acts models sensory-emotional counselling skills in such situations. The stories teach how empathy can support patients in any situation.

Here is one concept of empathy from oncology nurse/instructor Karen J. Stanley, who taught ethics and values needed in patient care (see end notes): “Empathy demonstrates an ancient idea that the eye of the mind sees concepts, the eye of the body sees objects, and the eye of the heart sees by entering into a caring relationship.”

Like Janie Brown, Stanley stresses the need to understand the patient’s reality. “Suffering can make a stranger of oneself, and that stranger may be too difficult or too painful to see in the bright light of anguish” (Stanley’s quote is by Younger, 1995, p. 71). Stanley describes how important it is for nurses to form caring relationships with patients. “Nurses are existential messengers and existential activists. … We journey into the world of suffering where we may be able to assuage the devastating loneliness and fear.” She calls for a quality of presence in oncology that inspires or infuses the stories in Radical Acts: “Presence is a gift of self, characterized by availability and openness. It is psychology and spiritual attention (listening, valuing, connecting, inner understanding or intuition, remembrance or reflection,” Stanley, p. 938).

The final section in Radical Acts is titled: “Surrendering To The Spacious Heart.” Six stories describe vivid and raw examples of restoration, ritual, and adventure with the wild. Here is Janie: “Witnessing four women who knew they would die soon immerse themselves in the vast winter sea changed me in some indescribable way. Since that day in 1998, and as the promise of my body’s impermanence settles in me, I remember those women and I say Yes more often to a whim, and surprise myself by overcoming a fear with a courage” (p. 229).

“Pity we can’t harness the energy of the great trees for ourselves or for people who need strength,” says Janie to a friend. The friend replies, “Just ask them for some energy and then thank them. They never say no” (p. 92).

Throughout the stories, Janie gracefully interweaves medical observation with her emotional responses. When she quietly assesses changes in patients’ bodies: circulation, respiration, liver, eye and skin colour, and as she describes the range of functioning at end of life, she involves the reader in what she sees and what she understands are physical signs of dying. I appreciated this. There is no “expert” role, no professional wall to hide behind.

How do we say goodbye?

Janie flies home to Scotland to be with her father Bill Brown, who is dying from a brain tumour. He is not fatalistic. Janie comments… “my beloved father, who showed me that death need not be frightening” (p. 282). “Everything passes,” muses her father, with philosophical acceptance. Bill Brown not only refers to accepting his imminent death, but also the passage of Janie’s grandmother from cancer years before (p. 274). Time, and many stories such as theirs, share a liquid quality in which death holds no hard edges when hearts open.

The Callanish centre in Vancouver, and the forest retreats hosted by Callanish Society at the Brew Creek Centre (near Squamish), provide a variety of support programs for people affected by cancer. In the Callanish writing group and expressive arts groups, people work with clay and painting. Their stories (also in the book) emphasise the power of ritual and creative expression to connect people with what is essential or whole in themselves. Readers can search the Callanish website for details and to see an exquisite film from one retreat.

Janie comments: “I have been deeply moved by the work I have seen people do to free themselves before they die, or to take care of their closest people after they are gone” (p. 136).

What is important at end of life?

Many people in the book, and at the Callanish retreats, can rage or grieve or experience ecstasy within safe community. Through this process, many discover unexpected joy. One patient laughs: “The cancer made me want to live; the irony of it all…” Another shrieks, “I hate you death!” Because they dare speak out, readers’ fears may diminish.

“Fear does have a way of shrinking the future,” Janie says to a friend who is a patient in palliative care. Not so for those who risk adventures, like Philip: “You’ve got to get ahead of your fucking cancer!” he promises himself as he rides his bike with Janie and others in the Callanish fundraising marathon. He confesses, “I … rode to conquer the hurts of cancer not just in my body but in my heart” (p. 213).

What is the legacy?

In Radical Acts, we meet the children of patients. One ritual with two small girls touched me. They sit with Daniel, their dying father, and they ask how to remember him. Janie suggests that the girls create a memory box while their dad is alive. The girls love this idea and ask Daniel to imprint his kisses on Kleenex (using mom’s lipstick). This they will keep in their box, along with their choices of other special memorabilia such as photos, gifts, stones. In this simple collaboration, a legacy of love is created that will sustain his family after his death. As much as this is a book about dying, equally it is about practical rituals that help loved ones to heal.

With another patient, a doctor, Janie and the family collaborate on a list of his fears, because he is paralysed with dread. As the list grows, his fear diminishes until he says, “And I’m aware of something else, too, that’s harder to describe, a settling deep inside me that I’m going to be ok no matter what happens” (p. 50).

Some spouses insist that their dying partner must not leave them. With one husband, the effect of his denial and resistance on his wife “…had wedged a cold stone of loneliness into her heart.” Janie counsels them, “There is often more peace in the room if family and friends accept you’re dying” (p. 86). This frees them to deal with the legalities of dying.

In such ways, and throughout Radical Acts, compassionate caregivers lend strength when people lose parts of themselves. Patients are sustained by the personhood of others (often a nurse) until their own recovers. Readers will learn that ‘presence’ can transform a cancer nightmare into a healing journey that is not limited by death.

Janie concludes Radical Acts with a sincere acknowledgement: :I am indebted to the grieving families of these remarkable people, who bravely read these stories and supported them being sent out into the world. They understand that death is not the end of a relationship and that the love never changes” (p. 279).

*

Lee Reid, age 75, lives in Nelson. A retired clinician from Nelson Mental Health, she is also author of three books about BC rural and coastal communities. Her stories, and her counselling work, centre around the values and health care needs of BC seniors. She has written a fourth book about the multicultural workers and residents who populated an historic extended care hospital in Nelson. Stories of Mount Saint Francis Hospital:1950-2005, illustrates a legacy of compassionate nursing care. The book will be self-published in 2021. She has also written articles and reviews featuring intergenerational education, rural home support care services, and the resilience and challenges faced by B.C. seniors. Her previous books are From a Coastal Kitchen (Hancock House, 1980); Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders (Nelson, 2016), reviewed here by Duff Sutherland, and Growing Together: Conversations with Seniors and Youth (Nelson, 2018), reviewed here by Luanne Armstrong. Editor’s note: Lee Reid has also reviewed books by June Hutton & Tony Wanless, Megan J. Davies & Rachel Barken, Ellen Burt, and Luanne Armstrong for The Ormsby Review. In 2018 she contributed a popular memoir of growing up in North Saanich, The Spider Hunters. Visit her website here.

*

References:

The Healing Power of Presence: Respite from the Fear of Abandonment, by Karen J. Stanley, RN, MSN, AOCN, FAAN. Mara Mogensen Flaherty Memorial Lecturer, 2002.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1169 Dying with love and compassion”