A ‘glimpse / to a new world’

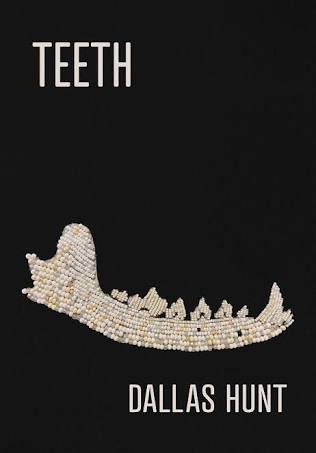

Teeth

by Dallas Hunt

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2024

$19.95 / 9780889714526

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

Dallas Hunt dreams of a world in which Indigenous people can speak of their ancestors in more than narratives of hunting and land sense, one in which they can be violent, devouring, beautiful, and mean, everything.

Teeth gives us hints of this world, such as this moment of exploded selfhood in “Blunt Teeth”: “something else is born / there, i’m sure it looks like / desire, bark, old piano / keys, and yet the taste / is cold coffee that / feels like love.”

A self as an environment, that’s good to see.

Of ancestors, Hunt has several kinds. Academic ancestors, for one (he teaches Indigenous Literature in Vancouver at the University of British Columbia).

That ancestry suggests Hunt has probably sat through a lot of seminars at the heart of settler culture, with demands on him like this, from the prose-poem “Rant as Review”:

it should adhere to the conventions of academic writing, or at least an

ethics of filmic engagement should guide a superficial acknowledgement

of Indigenous histories.

Hence this book, Teeth, which is often a kind of poetry with one foot in academic work that employs lyric techniques to release hidden information from field work and the other in contemporary Cree culture.

A second kind of ancestor, weather, is expressed, in “There’s a Poem for Everyone,” as: “I want a poem that doesn’t tell how difficult something is because colonialism has made it so, but rather the elements, our relatives, being assholes and hard to work with. probably on purpose and intentionally so.”

Of the relationship between these two sets of ancestors, in “Wrinkles” Hunt writes:

but how can you miss

the land so much

when you’ve been

so far away from it

for so long and,

when you hear its

whistle through corvids,

it irritates.

I like it. It’s sly, this push back against the academic “corvid” behind the mask of pushing back at a displacement of land-identity and its ravens, crows, and magpies. Such cleverness of doubled speaking mouthed out of a world formally denied societal space is worth the book.

Hunt is an urban man. Many Indigenous people are. Many have been so for hundreds of years in adaptation to the presence of the Hudson’s Bay Company and New France, becoming intermediaries in the world European technologies offered. Many others were urban for many thousands of years. It’s good to see a resurgence of civics that extend past settler power.

Or almost extend past it. For example, the kind of commentary (in “Floors”) about love “open to / a cartography / or open gate / to a portal, / partial but / a glimpse / to a new world” presents a self that is a mapping of land (both a colonial and an anti-colonial act). It chases love in a technical vocabulary and a poetics of breakage. It is utopian on one hand and, with its academic diction, a rather fraught path to intimacy.

Hunt expands that notion of breakage in “Ankwacas,” which relates the complexity, simplicity, and ad hoc nature of everyday spiritual relationships through a story of a dead urban squirrel framed by a story of a (settler culture) survivalist reality TV show. The attempt counters notions of settler notions of Indigenous culture with a narrative of the difficulty of ethical choices around the emblem of hunger. One could also just turn off the TV.

Hunt doesn’t. In “169 Anomalies,” a poem about the media language of a report on unmarked residential school graves, he points out that “169 bodies / in one acre” is not an anomaly when there are ‘two acres / left to search.” It’s a point well made and a grief well expressed. On the B side, it is brittle. The poem’s lack of punctuation is not managed well enough to prevent turning “country” and “acre” into simple symbols only hinting at meaning.

Even so, when Hunt talks of “children navigating a / world made too cruel / for them,” he is speaking as much of himself and the reality TV contestant in “Ankwacas” as about his ancestors, those buried children. The poem, however, doesn’t extend this generosity of shared shock and grief to the reporter whose painful choice of words sparked the poem. That gap says something about class and expectation. Educated, urban voices (as his is) appear held to a different standard than those of others, as if the pain of the dehumanizing word “anomaly” is as much a pain of betrayal within a university-educated class.

The missing generosity appears (brittlely) in the next poem, “Mâci,” where Hunt expresses some successes and failures at deftly speaking as the Earth, his “soft body” “torn apart / by spindly fingers / of ancestors,” devouring him, as well as by those “meaning well / yet somehow punitive.” In this buried world, he guesses that “all love / is a demanding pressure.” Guesses. The images are striking. The tentativeness is frequent.

In a style carried over from the poet’s first book, Creeland, in some passages Hunt employs acutely simple English, with simple shapes based on descending columns of words. They are direct, yet their music is often driven by the way words in English fall one after the other, such as, in “Do You Have Any Regrets!,” “You ask me / to sing you / a song to sleep // i pick a song / i’ve forgotten / the lyrics to // but i sing / it anyway.” This is colonial English. When you’ve lost your ancestral language, you still sing, with whatever language you have, however simplified.

One way to keep singing (or breathing) is to rely on bodily experience. It is not “the way / of our elders,” he notes in “Drowning in Healing,” “but we make do / we make / use of the everyday / as it makes use / of us.” It is wisdom through pain.

Another is to speak of a complex contemporary Cree metaphysics in a percussive tension between the slowness of extremely short blocks of syntax and the speed of their fall down the page. The tension pushes words forward because it is a performance created as much by reading as by writing. It also veers into sentimentality, as syntax-based writing often does. “[Y]ou find worlds / in people, / you find worlds / in a hug / without them,” writes Hunt in “Blue Whale Witness,” which is vague and ultimately unattached from the poem that precedes it. That’s likely because technique suppresses syntax, a large part of linguistic experience.

Fortunately, Teeth contains many moments of clarity that more successively cross between worlds. Given that all English in Canada is colonial, and all people have ancestral languages (English and its chiming poetics included), working through these crossovers is important work.

In Teeth, Hunt’s themes extend those of his first book Creeland (among them, a bristling porcupine, a traumatic birth, a smothering relationship with mothering, and awareness through excrement). The result is a textured surface, shifting between the personal (a poem of praise for convenience store workers, for instance) and an academic urban language of “immanent terrain” (found in “A Sun After Sleeping”)and “sight foreclosed” (in “Westmount Subjunctive”). It’s an honourable solution, although incomplete, given that academic and urban languages have their own entanglements with elite identity and power.

Fortunately, Hunt also adds Indigenous nuances to academic processes, without subjugating either. For him, each person is a world. When he places these worlds into an encompassing and emblematic sky and earth, independence is lost. It’s here that lyricism provides an open channel, representing two worlds at once, openly flowing between each other. Such moments make this book a must-read.

One of those moments—in “Maskosiy”—follows sky imagery and a view from an oil rig with “i wanted the world / but got the prairies instead / an earth that spreads and spreads and spreads.” Sky, earth, oil, bondage to difficult history, it’s all there at once. You can move back and forth through it. Beautiful.

It’s also good to see Hunt set the domineering syntax of English aside in texts like “hammer grass plough klondike // day plough buffalo heat // hoe flies night grain,” although, sadly, the laughter of its percussion is hard to hear or bear.

That might be the point. Hunt writes of the continuing seduction of using language as a defensive maneuver to throw up protective barriers with words, deterring injury by anticipating it. The approach is likely personally necessary, even while it limits the closeness that Hunt calls for, as well as the power of Teeth, which otherwise extends what official Englishes can do in the common work of freeing reading and writing from colonial modes.

*

Harold Rhenisch has written thirty-four books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for a memoir, The Wolves at Evelyn. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack and Out of the Interior. He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and worked closely with photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass, Motherstone, Cariboo Chilcotin Coast, and The Bowron Lakes; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. His The Salmon Shanties: A Cascadian Song Cycle will appear this fall. Harold lives in an old Japanese orchard on unceded Syilx Territory above Canim Bay on Okanagan Lake. [Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has reviewed books by Tim Bowling, Hamish Ballantyne, Zoë Landale, Kerry Gilbert, Robert Hilles, Sho Yamagushiku, Bradley Peters, Aaron Tucker, Dale Tracy, Dominique Bernier-Cormier, Selina Boan, Joseph Dandurand, Délani Valin, Robert Bringhurst, Rayya Liebich, Sarah de Leeuw, Roger Farr, Stephan Torre, Don Gayton, and Calvin White for BCR. His book Landings was reviewed by Luanne Armstrong; The Tree Whisperer was reviewed by Adrienne Fitzpatrick.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “A ‘glimpse / to a new world’”