1604 Plain talk at Tyee Lagoon

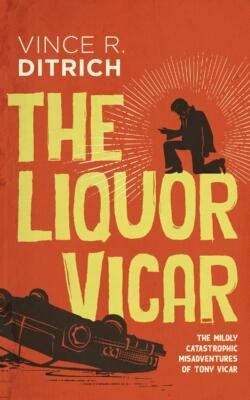

The Liquor Vicar: (The Mildly Catastrophic Misadventures of Tony Vicar, Book 1)

by Vince R. Ditrich

Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2021

$18.99 / 9781459747258

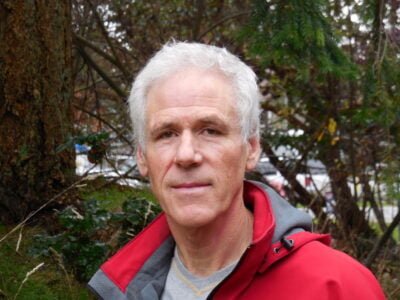

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

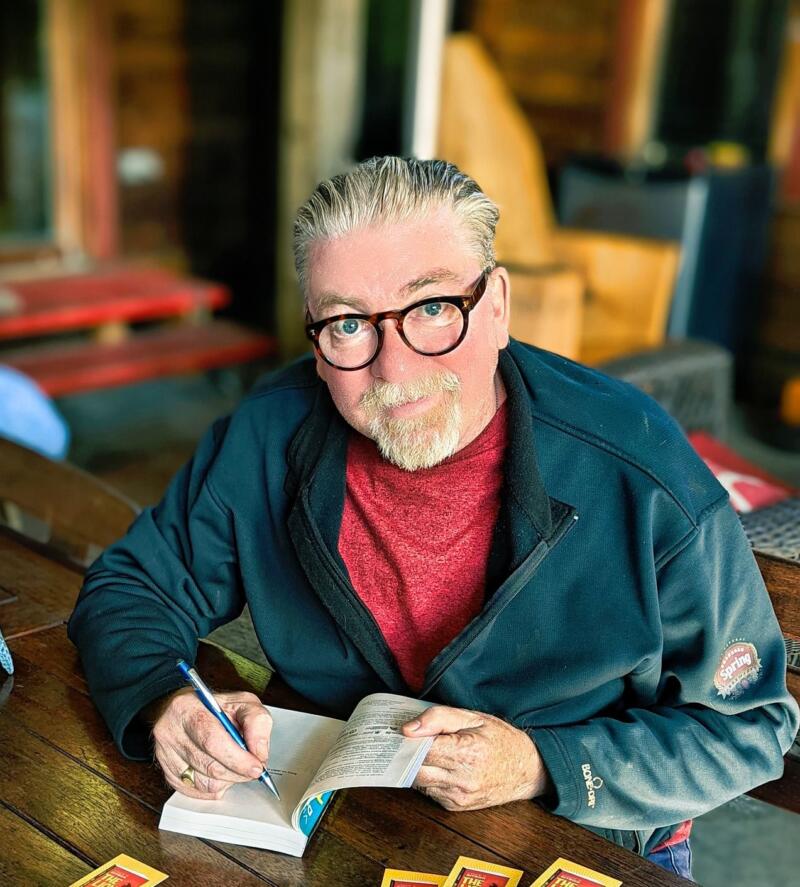

Vince R. Ditrich’s Liquor Vicar is a great big shambling bear hug and sloppy, bearded kiss of a novel. It is a novel jam-packed with irascible and freewheeling geniality. It is written by an author who is indecorous and unguarded almost to the point of recklessness — an author who goes out of his way to make sure his novel comes across as anything but a carefully crafted literary jewel. Credulity, common sense, and crafted control seem to be the last thing the author gives a flying fig to concern himself with.

Vince R. Ditrich’s Liquor Vicar is a great big shambling bear hug and sloppy, bearded kiss of a novel. It is a novel jam-packed with irascible and freewheeling geniality. It is written by an author who is indecorous and unguarded almost to the point of recklessness — an author who goes out of his way to make sure his novel comes across as anything but a carefully crafted literary jewel. Credulity, common sense, and crafted control seem to be the last thing the author gives a flying fig to concern himself with.

And yet. Not. All of this is a bit of a ruse. There is no question Ditrich has more than his fair share of novelistic smarts. He clearly knows what he is doing. And, most important, and contrary perhaps to first impressions, he cares about what he is doing — a lot.

Take the opening scene. A less than youthful Tony Vicar is deejay at a wedding dance. His bad-tempered contempt for the crowd, their values and their ignorance of music fuels his drinking. His mood is little improved by the time he dishes up his outrageous Elvis impersonation (in High Vegas mode). Ramped up by alcohol, he becomes an increasingly loose cannon. Catastrophe follows right on schedule.

With such an opening scene under their belts and with a broad grin firmly in place (for those propelled by a particular sense of humour), readers will find themselves strapping in for a whiplash-inducing ride — down twisting small-town and forested roads, past magnificent Vancouver Island views, in any one of the many character vehicles that careen through the book.

Purely on the level of action, the impact is wild and woolly. Within no time at all Ditrich treats his readers first to a good old-fashioned bit of physical pummelling and then to a fatal car crash and an intervention that is clearly a miracle. Or is it? The national media and swelling crowds of off-kilter true believers seem to think so. Chaos ensues. And not all of it is harmless good fun — though a lot of it is. The bit that isn’t, is almost the opposite of harmless good fun. It is skin-crawlingly dangerous. And weird. Deeply weird and more than averagely deranged.

The author knows how to do a busy business in tried-and-true suspense — managing with aplomb an abduction, a police stand off, a chase through a night-dark forest, and even a knife attack. Even more, though — and this is the real key to the novel– he knows how to counterbalance such derring-do with moments of quiet intimacy and gentle thoughtfulness.

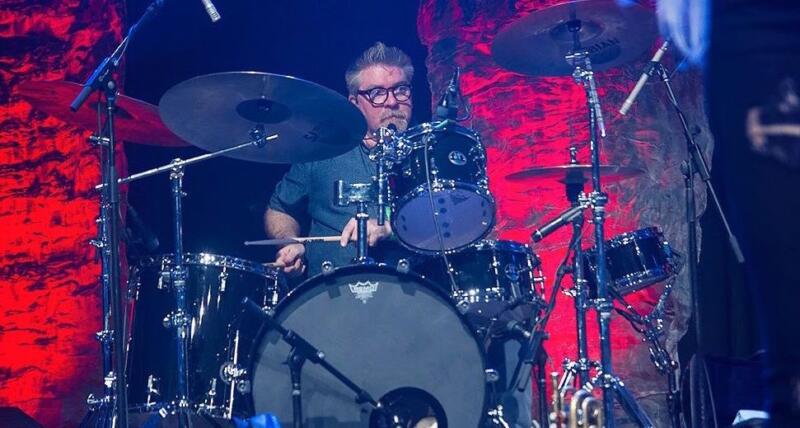

In fact, it is very much part of the timbre of Ditrich’s whole book that he plays off the crescendos with the diminuendos, the major chords with the minor. And the musical metaphor is particularly appropriate because — as many readers will instantly have twigged — the author is a member of the iconic west coast sometime Celtic-inflected “alternative rock” band, The Spirit of the West. Music, in all sorts of different ways, is never far from the writing.

Highly charged contrasts also infuse his handling of characters — and, more important, his vision of human nature. The character who carries the gigantic, unwieldy burden of the fitfully preposterous storyline is none other than the “liquor vicar” himself. Readers of twentieth century giant of fiction, Graham Greene, will instantly make the connection between the liquor vicar of Ditrich’s novel and the “whiskey priest” of one of Greene’s most famous novels, The Power and the Glory.

Both men, deeply flawed sensualists, are also, and particularly through the impact they make on others, much, much larger than life.

The very title of the book is also a joke: the protagonist’s surname is “Vicar”, and, yes , he works in a liquor store called, simply, “Liquor”. And don’t forget he is credited with being no mean miracle worker. Get it?

But wait: there’s more. The new woman in his life, Jacquie O, is taken aback when he suddenly seems more than she first thought: “I thought you were supposed to be just a drunk, “ she says. Most readers will share her surprise. After all, early on in the novel he further lays out his credentials as a brash and belligerent tough customer when he defies a sign forbidding food in a store by grinding his ice cream cone into the floor. After a cringingly ugly scene in a restaurant, also early in the novel, the very same Jacquie O offers up the two observations that not only has he been behaving like an “asshole”, but also that she has “never seen such rudeness in a public place.”

Surprises and reversals, not just in his serving up “miracles”, quickly appear. Arguably, it is just the opposite side of the same tough-guy coin that he should react to a swaggering and affected boor who has been physically abusing a vulnerable women by treating him to a furious bout of manhandling. It is, however, a different coin altogether that shows him transforming a superficial exchange with an old woman, Frankie Hall, into a relationship of deeply generous care-taking. Not only that, but, when Becky, the woman he has rescued from abuse, presents him with a “garland and tinfoil halo” for being her angel, he “grasped her hand tenderly, deeply moved. A tear spring to his eyes…and he mumbled, ‘Thank you, thank you.’”

For an author who is himself a musician, it seems only fitting that Ditrich should signal to his readers that his protagonist has deep wells to his character by showing how much he loves music. He truly loves music. Although not much of a performer himself, time after time, and clearly channelling the author, he responds to particular bands, even particular nuances of a recording with profound emotion and understanding. A man who can feel “a little catch in the throat” at a detail of a performance is clearly, Ditrich suggests, a man with depth. Further to hint at more depth than at first might appear, Ditrich has his protagonist characteristically think about a “Mandelbrot set” at one point and a few minutes later, “the very Olduvai of all information.” Readers get the message: this is a man with many different kinds of substance.

Even more important for the novel, Ditrich goes out of his way to emphasize how much Tony Vicar changes. Suggesting that he is, by default, early in the novel afflicted with a “dark, angry edge,” the author reveals how, as a result of the wild ride of experiences in the novel, a “new, changed Tony Vicar.” Importantly, as this new man, he reacts to absurdly overwrought popular fame with dismissive humility. Some novelists might make the highest moment of a protagonist’s moral growth his putting his own life in danger to save the woman he loves (though this the protagonist does). Not Ditrich: in his hands, the liquor vicar’s most startlingly human and penetrating act is something much gentler — a flow of desolating compassion for the dangerous and deranged woman who has threatened all that is precious to him.

It might seem to be asking a lot to expect the other, comparatively minor characters not to seem a little pallid in comparison. If anything, the reverse is the case. Take, for example, “Poutine”, the Quebecker owner of “Liquor” and Tony’s boss. Reeking overpoweringly of goat, clad in a decades-old denim outfit, and incapable of uttering much more than a single sentence without an ear-battering malapropism, he seems at first an almost improbable caricature. He might be capable of talking about “societal tissues” or saying things like “you look a little wrong in the tooth, dere;” he might smell “like he’d been fished out of a cesspool with a coat hanger,” but, repeatedly, as Ditrich makes amply clear, “The man was incredibly kind”, a “gentleman”. In many ways he epitomizes the kind of character the author clearly values most: “He was so rough around the edges that most people dismissed him out of hand.”

“Jacquie O”, Tony’s newfound lover, likewise seems — at first — hilariously improbable. An ex-stripper with a partial degree in psychology and a tattoo on her “mons veneris”, she gets her name from the Jacquie Onassis garb she — very partially — sported in her “dance” act. Like all the other characters in Tony Vicar’s immediate ken, however, she becomes a formidable force for good, a transformative power in the protagonist’s hitherto ragged emotional life: “Her vibe was like curling up in your favourite chair. Warm, soft, and as familiar as your teeth are to your tongue”.

Frankie Hall, an ancient tippler with the spirit of a jet fighter pilot; Farley, a Dacron-donning, drunken band member with no sense of rhythm or pitch and a crippling capacity for naivety; and “Con-Con” (aka Constable Constanz), a towering and imposing lesbian police officer, round out the central cast of characters. Caricatures? To a degree, yes. But that seems to be the point. While serving more than capably for Ditrich’s broad comic purposes, they serve, as well, a more fundamental purpose. All marginal characters from the perspective of genteel “respectability”, they all, with unostentatious depth of purpose and not a whit of self-consciousness — or even, perhaps, self-awareness — demonstrate genuine good heartedness, loyalty, and moral generosity.

Like so much else in the novel, these characters clearly serve both to wield the bludgeon of Ditrich’s rambunctious and often farcical humour, and, simultaneously, to radiate his values. Readers don’t have to wade very far into the novel to realize that the author has much to say. Even in the opening scene, Tony Vicar’s “edgy and resentful” internal tirade isn’t without a value-based target. The wedding guests that surround him, as he sees it, are people “with beige and white houses in the stupid fucking suburbs who’d never had an original thought in their stupid fucking lives.”

In fact, if there is one thing above all that seems to enrage the author it is the pretensions of wealth. Tony’s anger at a high falutin restaurant is hilarious but it is also laser-sharp. How could it not be when he takes aim at those who could believe that a “menu-browsing experience would forever change their expectations of life and give them a newfound reverence for ‘curated’ cheeses”? It is much the same values that lead to his extravagantly vitriolic contempt for a more-than-well-heeled health club in Vancouver: “In his minds’ eye, he saw imperial French heads rolling around in a basket, recently separated from their noble, aristocratic bodies because they couldn’t tear their focus from themselves as tout went to merde royale. Perhaps they could extinguish burning torches with seven-dollar bottles of glacier water. Or with cake made from free-range everything ….”

The characters of Tyee Lagoon, the unruly little town in which the novel is set, implicitly have more worth, more honesty, and more humanity than a whole large city of the pretentious wealthy: Frankie Hall, Poutine, Con-Con, Farley, Jacquie O, and, above all, Tony Vicar himself.

Further—at least in the spirit of the “magic realism” that the author trades in—the most deeply felt values of the novel may well come through the words of a mysterious stranger who, at the novel’s end, takes a doubting Tony gently in hand:

Sometimes folks… spend so much time worrying about affording stuff that any sense of wonder they have is left immature, stunted. They really don’t spend a minute developing wonder as a mental tool. Wonder can cause explosions of inspiration, or subtle nuances of the spirit.

And what better means of delivering these thoughts in a novel itself full of “wonder”, than via a fine fellow called Gary. After all, Gary is an angel.

Or is he?

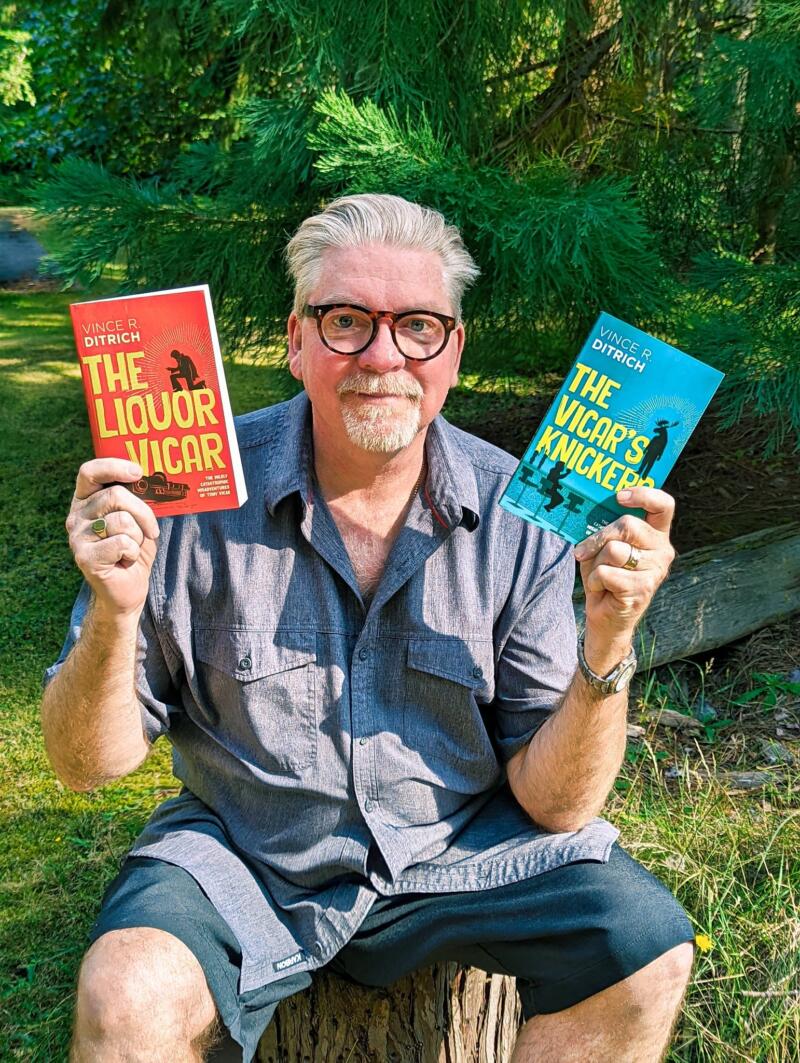

Those who want more of Tony Vicar will be pleased to know that a second novel about him is now out. The Vicar’s Nickers is, like the first, full of “mildly catastrophic misadventures.”

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Madeline Sonik, Alex Rose, Frances Peck, Naben Ruthnum, Rowena Rae, and Kamal Al-Solaylee. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

9 comments on “1604 Plain talk at Tyee Lagoon”