1413 Teaching watershed warriors

Upstream, Downstream: Exploring Watershed Connections

by Rowena Rae

Victoria: Orca Books, 2021

$19.95 / 9781459823921

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

A children’s book that is also a call to arms? Without so much as a single sabre rattle, a new book by biologist and writer Rowena Rae, titled, disarmingly, Upstream, Downstream, and subtitled Exploring Watershed Connections makes a vital contribution to the “Orca Footprints” series, a collection of children’s books from Orca publishers, all intended to encourage “Small Steps Toward Big Changes”. It is only too appropriate that the last Chapter in the book is called “Watershed Warriors” and that the last line in the book is “Let’s all help watersheds so that watersheds can help us in return.” Even so, as a call to arms, this book could hardly be more cheerful, friendly, encouraging, and engaging.

A children’s book that is also a call to arms? Without so much as a single sabre rattle, a new book by biologist and writer Rowena Rae, titled, disarmingly, Upstream, Downstream, and subtitled Exploring Watershed Connections makes a vital contribution to the “Orca Footprints” series, a collection of children’s books from Orca publishers, all intended to encourage “Small Steps Toward Big Changes”. It is only too appropriate that the last Chapter in the book is called “Watershed Warriors” and that the last line in the book is “Let’s all help watersheds so that watersheds can help us in return.” Even so, as a call to arms, this book could hardly be more cheerful, friendly, encouraging, and engaging.

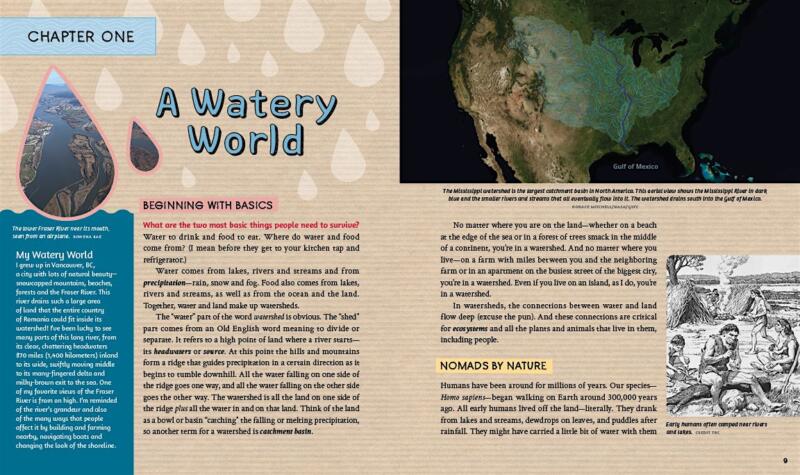

Rowena Rae has clearly put a lot of thought into the best way of motivating her young readers. First off, both main title and subtitle evoke issues in the most attractive ways. There are few more alluring pleasures for children of all ages than the water molecule. Few children would not perk up at images of flowing, delicious, splashy streams evoked by the words “upstream” and “downstream” — even though they may not (like their wily parents or teachers) think of the metaphorical notions of upstream-causes and downstream-effects.

The subtitle is likewise carefully gauged to entice the wondering child, particularly with the surprises and fun associated with the word “exploring”. (Think: Dora the Explorer.) (As for “watershed” and “connections”, the principles underlying these words of the subtitle are a little more elusive and need the rest of the book for the author to develop.)

Other elements of the book are likewise engaging. First, the layout is bright and colourful — dominated by blues and greens — rich with a broad range of photographs, many of children. Second, Rae employs language that combines a tone of substantial and serious factuality with other, lighter tones. Of rivers that are rerouted to be absolutely straight, for example, she warns they “can swell in the blink of an eye”. Of damaged watersheds she likewise appeals to children’s experiences, writing “think about a hockey or basketball team. A player with a sore ankle or sprained finger can still play the game but not very well. As a result the whole team suffers.”

At the same time, the author doesn’t overlook the effectiveness of questions in lieu of daunting children with an unbroken chain of pronouncements. At one point she writes, “Why should we know such specific things about land cover and land use in a watershed?” At another she asks, “What, you ask, does the Industrial Revolution have to do with watersheds? Everything!”

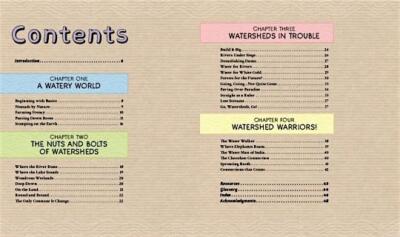

Likewise to break up the flow of facts and explanations, Rae organizes the text into an easy array of bite-size sections. The four chapters make a neat and logical sequence. The first on the history of humanity’s attempts to manage water is enticingly titled “A Watery World”. It is followed by a chapter on “nuts and bolts”, an explanation of the physical science of watersheds. Some science-for-children books might stop there, but not this one. The next chapter follows logically — and a little threateningly: “Watersheds in Trouble”. Most important for the book, though, is the sequel to this chapter, “Watershed Warriors”, a series of portraits of inspirational people — grass roots people — and their campaigns.

Likewise to break up the flow of facts and explanations, Rae organizes the text into an easy array of bite-size sections. The four chapters make a neat and logical sequence. The first on the history of humanity’s attempts to manage water is enticingly titled “A Watery World”. It is followed by a chapter on “nuts and bolts”, an explanation of the physical science of watersheds. Some science-for-children books might stop there, but not this one. The next chapter follows logically — and a little threateningly: “Watersheds in Trouble”. Most important for the book, though, is the sequel to this chapter, “Watershed Warriors”, a series of portraits of inspirational people — grass roots people — and their campaigns.

Even these chapters are further broken into bite-size subsections of about half a page each. The titles to these smaller blocks of texts are as strategic as the whole structure, combining information with lively wording, whether somewhat threatening (“Stomping on the Earth”), a little hopeful (“Going, Going…Not Quite Gone”), enthusiastic (“Go, Watersheds, Go!”), or deeply appealing! (“The Chocolate Connection”). Complementing these easily accessible short sections are the even shorter factoids (of sorts) popping up in the broad margins under the heading “Ripples”. Adults take note: most of these are fascinating, in or out of a children’s book: “The oldest known wells are on the island of Cyprus in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. They were dug 6.5 feet (2 meters) wide and 26 feet (8 meters) deep to reach water in the ground. These wells were dug at least 10,000 years ago.!”

Further to engage a young reader, though, is what Rae has done with her own personal story. Rather than remaining the invisible voice of authority, she occasionally brings a few of her personal experiences into the story: her young readers will very much feel that they are in the company not of an “author” but of a real, live person with a valuable and interesting background. A photo of Rae holding up a long rod showing the thickness of the ice in a lake in Antarctica, taken when she was working there while a university student, for example, will impress any child — especially when she concludes her story with details sure to get rapt attention: “Everything we took in with us had to come back out. And I mean everything. Yup, that included our urine (collected in metal drums) and faeces (collected in plastic buckets.)” Find the child whose attention won’t be riveted on this morsel of information.

Included in this story of the trip to Antarctica is the fact the ice was 6 metres thick. This number, like the depth of the oldest known wells quoted above, demonstrates something else about Rae’s way of impressing young minds. She loves numbers. Any child who likewise feels the power of numbers and the realities that lie behind those numbers will be much swayed by what the author does with her numbers. At one point she does write, as a gentle challenge, “big numbers can make your head swim.” This admission does not, however, stop her from filling her examples with arrays of startling and eye-popping numbers, even while she makes sure to present them so that they are easily understood. “In the early 1900s, the Aral Sea had about 10 parts of salt in every 1,000 parts of water. Think of a large quilt made up of 1,000 squares. In the Aral Sea, 10 of those squares were salt. In the ocean, 35 squares are salt.” (Spoiler alert: with the effects of diverting the lake waters for irrigating cotton fields, the salinity in the Aral Sea has increased tenfold).

The fact that Rae has used the example of the Aral Sea demonstrates yet another way in which she manages to give colour and life to her writing. Far from being focused on local or even Western issues, the author has taken seriously her goal to write about “connections”. As she makes convincing — and fascinating — issues of water use and the connections between water use in one place or one time link importantly to other places and other times. Her stories and examples could hardly be more international. Her examples of wetlands now under protection extend from South Korea to the Democratic Republic of Congo. Her examples of inspirational activists include the Wiikwemkoong First Nation in northern Ontario, Angola, India, Philippines, and Ecuador. And so on.

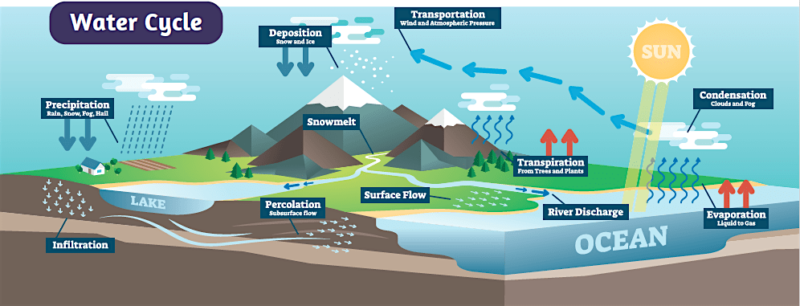

This list of Watershed Warriors as the concluding chapter of the book points to probably the trickiest element of a book like this for the author to manage, and one that no doubt Rae had to consider deeply. Clearly, it is important that she engage her readers — the array of strategies she has employed makes that amply clear. At the same time, she feels it to be important — because it is important — that children come away from her book with a solid foundation of knowledge. In all of her chapters, but especially in the second chapter, where she explains the science behind watersheds, she does not trivialize her subject matter. On the contrary, even in her use of proper vocabulary — terms like “impervious”, “catchment basin”, “riparian zone”, and “hydrologic cycle” — she wants to give young people the intellectual tools to make them effective. The Glossary at the end of the book goes further in making this function even more substantial.

Probably just as important in Rae’s calculations is tone. Yes, she is often breezy, bright and lively. Yes, too, in the third chapter, “Watersheds in Trouble”, she gives some deeply alarming — even depressing — information. The balancing act, therefore, and one that she does as well as probably anyone could, is to convince her readers of the seriousness of the issues without paralyzing them with alarm, or, even worse, perhaps, provoking them to turn away in denial.

From a broader perspective, too, it is appropriate to her audience that Rae has decided to keep her focus very much on the phenomena of water use and abuse rather than on the socioeconomic, ideological, or geopolitical forces that lie behind many of those abuses. Though she does make amply clear the effects of the Industrial Revolution on the increasing damage to watersheds, she wisely does not attempt even to hint at the driving forces of multinational corporations, short term or profit-driven thinking in governmental policies, or corrupt subversion of environmental protocols, all of which we know to be overwhelming culprits in watershed damage.

It is enough — indeed, it is more than enough — that Rae has successfully shaped her subject matter in a way beautifully calculated to have children deepen their understanding of water use, and, in feeling “connections”, become inspired to take “small steps towards big changes.” It is hard to see how many children will reach first for a book like this, no matter how appealing, rather than a book about ponies or wizards. With a thoughtful adult at the helm, however — possibly a home schooling parent — this book could make a real impact on children’s understanding of their place in the world.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Visit his website here. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Kamal Al-Solaylee, Bruce Baugh, Rahela Nayebzadah, Genki Ferguson, Keath Fraser, and Matthew Soules. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1413 Teaching watershed warriors”