1478 Coastal flux and depth

A Killing at Easter Hill: A Season of Fragments

by Alex Rose

Vancouver: Walhachin Press, 2021

$16.00 / 9781777582319

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

A Killing at Easter Hill is available for sale at People’s Co-Op Bookstore on Commercial Drive, Vancouver

*

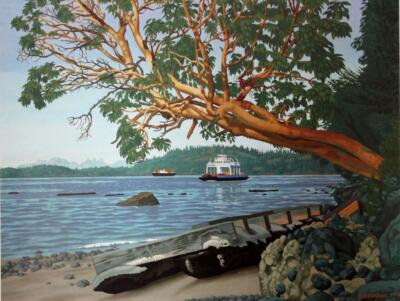

One of the advantages of a novel over a book of poems and other short pieces is that a novel can immerse the reader into a vividly real world, a world of an intensely imagined geographical setting and memorable characters. Yet, in a tiny book of what are titled “Fragments,” Alex Rose manages to achieve some of the effects of a hefty novel. The reader of A Killing at Easter Hill: Season of Fragments is likely to leave the book with a strong sense, first, of the British Columbia coast, and especially of inlets, bays, settlements, anchorages, and stormy crossings. Even more, though, the reader is likely to carry away a strong sense of almost hidden lives — and the highly charged experiences that reflect those selves.

One of the advantages of a novel over a book of poems and other short pieces is that a novel can immerse the reader into a vividly real world, a world of an intensely imagined geographical setting and memorable characters. Yet, in a tiny book of what are titled “Fragments,” Alex Rose manages to achieve some of the effects of a hefty novel. The reader of A Killing at Easter Hill: Season of Fragments is likely to leave the book with a strong sense, first, of the British Columbia coast, and especially of inlets, bays, settlements, anchorages, and stormy crossings. Even more, though, the reader is likely to carry away a strong sense of almost hidden lives — and the highly charged experiences that reflect those selves.

Alex Rose’s world is one of people at the edges, a world with a lot of music, a lot of alcohol, a lot of conversation, and a lot of violence. Readers of Hemingway may feel some recognition in encountering a sensibility where hard talk, hard lives, hard drinking are rooted, almost anomalously, in a sensitivity to the beauty and power of writing and music.

The very word “fragments” has many different implications. The word can suggest that which was (or tried to be) whole — possibly whole lives — has been fractured. Second, it can suggest the retrieved recollections of what has been largely lost through time. It can, third, suggest the author’s method of writing, a way of merely dealing out pieces, while possessing a fuller, unspoken, reality. Finally, it can suggest only those prismatic glimpses from which the author has been largely excluded but has been careful to glean. In fact, all four seem relevant to understanding the ways in which Rose handles the materials in this book.

The book’s epigraph, a quotation from Virginia Woolf, starts the ball rolling: “A flux of random associations in a season of fragments.” In fact, the words “random associations” are as misleading about what Woolf did in her own novels as what Rose does here. The phrase “season of fragments,” however, does evoke the specific circumstances in which the author has put together the book. “To escape the deadly Covid-19 pandemic … the author and family” cruised through B.C. coastal waters: “many of the fragments in these pages were written — or completed — during that sea voyage.”

Visually, some appear — and read — as “free verse” while others are presented in blocks of text approximating (but never quite settling into) prose.

In terms of content and development, though, they nearly all have something in common: time. The main title “A Killing at Easter Hill,” epitomizes the main driving energy in every piece — explicit or implicit narrative. That title, sounding a little like that of a folk ballad, suggests that, in some ways, Rose is re-making the form. Where the narrative focus softens into pure evocation, though, many of the pieces are very much like the “epiphanies” made famous by James Joyce — short, recorded pieces that are left to stand in their own terms without apparent point other than that they reflect the wonderful strangeness of the commonplace.

In “Sutil Point,” for example, Rose recalls a choppy crossing that ends in a marina where a young man deftly climbs up the mast of a sailboat. The piece ends, simply, “Later that afternoon, we drank beer on the dock and stared at the sailboat, its mast piercing the mantle of the sky.” Apart from the use of the metaphor, “mantle” to stir some resonance into “sky,” the whole incident, taking place within a few hours, dwells in its own oddly haunting, but purely implicit, space.

At the same time, this piece will, for some, read almost like a journal entry. Many of the pieces, in fact, have a similar texture. The very title of one such piece makes much of the point: “St. Cecilia Day — Anne Drops in on a Session at Graveyard Sound” records a few hours in one day, with, indeed, “Anne” paying a “surprise visit,” while the writer and some fellow musicians “played two complete songs for her.” Anne dances and, after two “exhausting” hours of “concentration,” the group discovers they have failed to turn on the recording device. Like most such apparent diary entries, this one does not unfold into emotions, metaphors, or reflections or otherwise employ any of the conventional methods of “expressive” poetry. It merely stops.

Much the same journal-entry quality characterizes “Carol & Cleve,” the recollection of a night in a pub and the encounter with a “famous Vancouver poet — drunk as a fiddler,” uncontrollably peeing himself. “In Our Minds We Went to New Westminster” similarly records a visit to “Thorkild” to do some joint editing, followed by a visit to a bar, and, almost visionarily, Thorkild’s revealing a “hedgehog named Taavi.” The piece concludes, “I began to think, at some point, Thorkild might tell me how much he loved Taavi — though he never did. Not a word.” Like the other such diary-like passages, this one achieves its impact by refusing to go beyond the moment itself, to leave the oddness and ordinariness of the incident to play off against each other entirely in the reader’s perception.

Other passages, however, take the narrative in substantially different directions. In these passages the writer does largely disappear behind the recorded facts, but only up to a point. The framing, like the tonally inflected language that reports the incidents, tilts the otherwise neutral impression. “Tug-Death of a Cuckold” is particularly rich with pointillistic narrative fragmentation — but suggested depth. The effects are partly achieved by the fact that an incident is told by Dave and Molly, locals who are deeply suspicious of the role played by Saskia in the death of her partner, Tug. “Several days later, divers arrived from Campbell River to work the channel, but no body was ever found.” A “senior homicide detective” finds nothing and we are left with only Dave and Molly’s suspicions. Except. Except. The piece ends, “After things died down, Saskia became a recluse and moved to Hixon, Alberta.” “Molly, suffering from vascular dementia, went into Libby Lodge soon after Dave died from a sudden cardiac incident.” And that’s how it ends. The telescoping out and jump forward cry out to be followed by thoughts on, say, the icy finger of unknowable and wayward mortality. But, no. All we have is the “sudden cardiac incident.”

Amongst other pieces like this, “Snag: Corpse on a Crofton Log Boom,” and “A Killing at Easter Hill,” the latter almost – almost — shows the author participating emotionally in the story. Piers and Denise, it seems, have a pond for exotic fish, until, that is, it is raided by raccoons and herons. Piers, however, acts. He kills a heron. “As if in supplication, he held it up to her — that bleeding and broken thing.”/ “For the first time, Piers killed for her. And both were very happy indeed.”

In all three of the pieces, all with violent death, Rose stays outside, observing, almost coolly. In the last of these, though, the lenses through which the death is presented darkens the image: the ghoulish “bleeding and broken thing” pivots into the irony of the final word in the piece — “indeed.”

Some of the most memorable pieces combine and expand on both of these methods, the personal diary entry and the detached journalistic account of others. The author achieves a particularly poignant effect when just a few “fragments” illuminate not just an incident, but suggest a whole life. In “That Summer at Squitty Bay,” for example, while in a kind of rented retreat, the author meets “Milo,” the caretaker — and his rifle. Accounts of his skill with the rifle as a Czech freedom fighter and, locally, in his encounters with drug dealers (accompanied by more stories of violent death) leave possibly the deepest impression in spite of the quiet and only faintly sinister conclusion. The author fails to learn how to hunt from Milo, but Milo delivers: the “rack of wild lamb” Milo brings is, we are told, “the best meal of our lives.” Indeed.

Of course, Milo’s life story is merely suggested, but it is difficult not to feel that his whole life is somehow present in these very few fragments. “O Simian Rind” uses a similar method, this time in free verse form. Here the whole life story moves from days of an unnamed youth with “the bones of his face delicate, frangible,” to the point, “coarsened by age, come a thickness of feature”, and, ultimately “coffin time.”

By this point it will be apparent that Rose draws repeatedly on the sense of authenticity evoked by names. In these pieces, peoples’ names function a little like talismans or ciphers, or, in other ways, a little like the names of the coastal features with which the writing is peppered. With nearly all of the names of people comes a deeply rooted sense of identity.

And, yet, in some ways the most interesting people in the book are the author and the author’s family members. Although there is little introspective or confessional writing, portraits gradually emerge of a father, a mother, an “Uncle Tone” and, most centrally, the author. The opening poem, with the line, “You with your walker and I can barely drive” establishes a time frame to bracket the other recollections. In “Incidental Fumble & Strum,” one of the pieces about playing music, a similar line, “Arthritis notwithstanding,” says much about the author’s life circumstances.

Other details, though, suggest a past jigsaw life of varied jobs and locations. In one piece the author uses a turning point as a fulcrum for what follows: “A deck hand in the merchant marine, I paid off the MV Crystal Sea in LA to fly back home — to Horseshoe Bay.” In “Last Shift at St. Paul’s” the turning point is even more charged, slightly more internalized. As a “hospital worker paid by the ministry of welfare to clear patients out of the ward once the medical staff had treated them,” Rose is threatened by a violent and unhinged patient. He quits. In “A Conflagration for Gurov,” a colourful and dynamic encounter leads to a more encompassing reflection on the writer’s life: “My place but a regional, a book on a BC ferry/ A weekend lifeguard with a mortgage/ A part-time driver — shuttling blood products around a harbour town, lab to lab.” While all of these are recorded in a largely neutral voice, the sense of clear-eyed understanding, while not exactly suggesting a life of quiet desperation, creates a poignant distance from a past now registered only in fragments.

Much the same impact, though possibly more trenchant, arises where the sense of a past channels through recollections of family members. The family member who appears most, and whose life frames a whole piece is Uncle Tone. Rose gently traces a life from golden boy to addiction and early death. The author’s father and his totem-like singularity are closer. He appears simply as an old man in one piece about viewing fireworks, but in “Llamas,” his character is brought into sharper focus: the 82-year-old, “oiled on cheap rye,” has broken both arms in a fall, and is “now unable to wipe his own ass.” His wife, Helene, apparently estranged, having made short, brittle appearances elsewhere in the book, here is clearly embittered and bad-tempered. Insisting, “I never did love your father,” she makes crystal clear she will not help with any “personal care.” The poem, like others, creates a quietly stirring effect by juxtaposing the central moment with the brutal face of time’s power. The poem ends by recording both of their deaths. The closest the author comes to commentary, however, is to assert early in the poem, “We were a family out of sorts….”

Importantly, though, this piece is followed by a passage written in italics. In the passage, the author writes of the discovery, in Peru, of an ancient site that reveals that “mothers and fathers,” by way of sacrifice, gave up the “mangled and bleeding corpses” of their children. The point is clear.

This use of a kind of italicized end-note, in fact, is one of the ways Rose enriches the impact of the pieces, though never in a consistent or predictable form. Some of the italicized notes provide additional information, some an ironic exclamation, some an apparent sidebar. In “A Conflagration for Gurov,” for example, the piece is followed by biographical information about Gurov’s colourful, political father. Again, though, the final line is made disturbing by its very indirection: “Exhausted, but ever fierce, he often used the belt on Gurov.”

In some ways, perhaps, the most illuminating poem for what it shows about the creative energy underlying this whole little volume is a piece called “Hardscrabble Farm — The Poet in his Compound.” Much about the writing here is typical. There is the coastal setting, this one on Saturna Island, with “twisted Arbutus, moss and sculpted sandstone ridges,” there is the ample alcohol, there is the encounter with a local poet and the “writerly chat” that ensues, including reference to European greats (in this case Gerard Manley Hopkins at one point and W.B. Yeats at another). What is most illuminating, though, is what Rose records of the moment when the poet, Brendan, encourages the author to “write more poetry and be damned with the magazine business.”

Although it seems that Brendan partly takes back what he says, his words are enough to make the reader alert to the power of the moment. It may be that Brendan gives, as his final advice, “Don’t type …. Live.” The fact is, however, clearly Rose has taken both strains of the advice. If this little book is anything, it is testimony to the way that the lives of others, essentially elusive, can be known only through fragments of language and memory.

Some might, understandably, be bemused that the book makes no claim — outside this instance — to be “poetry.” While there is little to be gained by fussing over the term, it is unquestionable that these pieces use many of the methods of poetry — the overall shape of each piece is carefully crafted, particularly geared towards the cadence and ripples of unspoken association created in the final lines. In fact, so little is stated directly and so much left unsaid, almost every short piece exists mostly in its margins.

It is true that the private references, even the geographical spots, are so numerous that the pieces seem, at times, mostly written for Rose and no one else. The writer does produce a few moments of social critique (two poems in particular make acrid digs at the forest industry; another hints at the narcissistic self-importance of the Vancouver artistic elite). For the most part, though, the writing seems to reflect the desire to distil into words the ineffable strangeness of the ordinary, the moments and people — including even the author– who pass into and out of life sometimes radiating light, other times casting shadows, but never making either their inner lives fully known or fully comprehensible.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Visit his website here. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Frances Peck, Naben Ruthnum, Rowena Rae, Kamal Al-Solaylee, Bruce Baugh, and Rahela Nayebzadah. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1478 Coastal flux and depth”