1439 The language of the pitch

A Hero of Our Time

by Naben Ruthnum

Toronto: Penguin Random House (McClelland and Stewart), 2022

$22.00 / 9780771096501

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

Take a popular poll on who best exemplifies a “hero of our time” and you might expect answers to include a Nobel peace prize laureate or a billionaire philanthropist. Pose the same question with a sarcastic roll of the eyes while leaning hard on “our time,” you might get as an answer a slightly stupid 28 year-old high school dropout web-multimillionaire or you might get a charismatic and ruthless corporate leader powered by mind-numbing rhetoric. Possibly, though, you might get an unobtrusive man from a “visible minority,” navigating his way cautiously amongst the powerful and ruthless. In this novel Naben Ruthnum creates all three characters — and other possible claimants to the title — while directing the third of these to take the helm of the narration.

Take a popular poll on who best exemplifies a “hero of our time” and you might expect answers to include a Nobel peace prize laureate or a billionaire philanthropist. Pose the same question with a sarcastic roll of the eyes while leaning hard on “our time,” you might get as an answer a slightly stupid 28 year-old high school dropout web-multimillionaire or you might get a charismatic and ruthless corporate leader powered by mind-numbing rhetoric. Possibly, though, you might get an unobtrusive man from a “visible minority,” navigating his way cautiously amongst the powerful and ruthless. In this novel Naben Ruthnum creates all three characters — and other possible claimants to the title — while directing the third of these to take the helm of the narration.

In 1840, Russian novelist Mikhail Lermentov published A Hero of Our Time. The fact that Lermentov made his “hero” a Byronic cynic speaks volumes about Lermentov’s views on his contemporary society. The fact that Ruthnum uses the same title forces his readers to keep their gaze not just on the fate and fortune of his “hero” — or, arguably, heroes — but on the world as it is. Now.

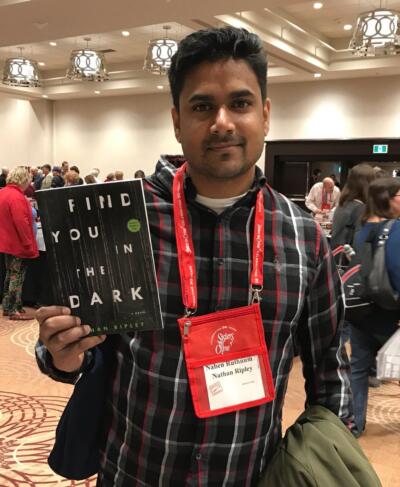

In his two previous novels, Ruthnum chose to write “thrillers” under the name Nathan Ripley, thereby distancing himself from “Curry” writing that might be expected of an author with his real name. In Curry: Eating, Reading and Race, however, as the title suggests, he took the opposite tactic. In some key ways his new novel is a coalescence of the two approaches: its narrator (and other chief characters) are South Asian, yet the plot abounds with exactly the kind of thriller-based suspense that, in an interview, Ruthnam said he wanted to use in a “literary novel.”

Subtle at first, the increasing suspense very much shows the thriller-writer at work. His titular hero even acts a little like the hero of a thriller. Hoping to find incriminating evidence against his new, ruthless boss, Olivia Robinson, Osman Shah undertakes a harrowing backwoods quest. A fraught escape and, subsequently, a complex plan to enlist unlikely allies to orchestrate a public takedown build towards a climactic confrontation riven with dramatic challenges, counter challenges, and power reversals. And, to ramp up the suspense, Ruthnum charges his plot with many of the tropes of the dystopian satire: throughout the story, but in the final pages in particular, he evokes the nightmarish ambiance of the dire dystopia.

To lead his readers along this roller coaster ride, though, Ruthnam has created the remarkable narrator, Osman — and, arguably, as much the book’s centre of gravity as the plot. Admittedly, Osman first comes across very much as the average “anti hero”. In the words of his sometime lover and best friend, Nena, “You’re a mediocre, pleasant Indo-Canadian, the perfect hyphenate-union of cultures to elicit zero interest….” In his own words, he says, “reliably I spoiled everything” and, more, trenchantly, sighs, “What reading thousands of novels has taught me is that I am a coward.” Even more acridly, he feels himself virtually extinguished in the eyes of assertive men, those who “saw men like me as ambulatory innards, as an exposed nervous system obscenely alive but with no place in this environment.”

It helps not at all that, as Osman keeps insisting — with worrying relish — he is physically loathsome, fat, sweaty and malodorous. Relentlessly, repetitively, he lingers over his most repellent qualities: “my oily face, impregnated with its sebum custard, and the souring mollusc pheromone stench that drifted through the helpless cloth over my armpits.”

As if to emphasize how different he is from a real “hero,” he admits to a fantasy of rescuing Nena in a scenario where “my body became a fluid bulk of death-dealing movement” — only to decide that Nena has set him up to expose his “failure to do anything helpful, protective or strong.” Is this “a hero of our time?”

And yet. And yet. If Ruthnum were to have sustained this treatment of Osman throughout the book, the reader’s experience would have been limited. Instead, he uses Osman’s part-time ally, Vikram, to challenge Osman’s misleading exterior as merely seeming “one fucking big blank that you feather with jokes and brushoffs….” In fact, Vikram argues, Osman’s behaviour suggests “depth” that “absolutely must mask pain and the real shit.” And Vikram is right — Ruthnum makes sure we have spent enough time with Osman to know he is right.

For the fact is — and, in many ways, this is the most affecting impact of the book — Osman increasingly shows himself capable of unassuming but sincere love, primarily for Nena, but also for the memory of his dead, estranged father, and for his wonderfully living but also estranged mother (the most enchanting character in the book). Again Ruthnam reveals an obscured side of his protagonist through the words of someone close to him, Nena: not only does she show Osman’s version of his body to be a concoction but also, as she says, he most “wants out of himself and into something else.” In a passage in the end of the book, beautifully reminiscent of the much-celebrated conclusion of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Osman withdraws behind his own story, “letting any identity I have possessed in public or private reality vanish.” How? His answer is both moving and evocative. As a hero of our time, Osman isn’t, after all, so disappointing: he will vanish “by saying my last long piece, putting it before you, and disappearing behind it.”

“You”? “my last long piece”? What is he talking about? Ruthnam provides no explicit answers to these questions, but he has been careful to weave an intriguing tissue of “meta” fiction over the entire narration. In one passage Ruthnam has Osman talk about his own views of novels. For all the drive for “human lessons” in novels, he says, “aesthetics and purpose and art…are the true point of the fucking things.” Most readers, he grumbles, “want a warm, vivid capsule of any idea, situation.” However, in his own terms — and this is where the connection between Ruthnum and Osman is suggestive — Osman says, “I could find and conceal myself in novels.” For him to add, “But this shadow could only acquire dimension if I lied to make myself seem worse as much as I lied to make myself seem better,” is surely to make the thoughtful reader sit very much up to attention. And, if this weren’t enough, about the very substance and thought of novels, Osman adds, “the only wisdom in books is the manifested struggle to understand the deeply felt theories flung out in quavering courage only to be rescinded or corrected by the plot or a wiser or no-less-stupid character….” He could offer a worse hero than a “no-less-stupid character.”

The impact of these thoughts at this point in the narration is all the greater because Ruthnam has (to invoke Keats) “teased us out of thought” by making tiny jabs at our sense of the novel’s fictional “reality.” At some times, he has Osman imply that what we are reading is a kind of autobiographical account: “I have noted it all down as I remember it.…” Yet, later, Nena says she barely recognizes herself in what he quotes her as saying. It helps not at all in keeping the realities neatly lined up that Osman reports that much of what he writes he reads over the phone to his mother’s voice mail, including “a passage about Nena that hasn’t survived into this draft.”

Into all this, Ruthnam occasionally inserts a shadowy “you” : “I cannot explain to you,… that is the purpose of this part of the story, to add to your knowing of her.” Readers of such recent novels as Booker prize winner Anne Enright’s Actress, will be prepared for this kind of second-person enigma. While the “you” largely sits politely in the background as a kind of “dear reader” figure, this is not always the case. At one point, in fact, the “you” becomes “frustrated by what seems to be my mania for avoidance” — something, incidentally, that seems surprising given the devastating intimacy of Osman’s revelation. In fact, his claim that he can’t write with “invisible subtlety,” but instead, must “write as I joke” seems to refer to an entirely different kind of writing from that which, for much of this novel, Ruthnam produces.

On the contrary. An additional quality of the writing that should be evident by now is its sheer brio. Ruthnam — and his creation, Osman — are clearly fascinated with language. Some readers may feel that while the book is most centrally about the revelation of self, heroic or otherwise, it is, almost as centrally, about language. A tone deaf reader will miss much. The opposite sort will be fascinated.

Some of the most striking language is very much in Osman’s own voice. As the narrator, both penetratingly astute and inventive, he is often hilarious. In describing how the pastor of a white supremacist church leaves the pulpit, he reports his “catching the rubber toe of one of his Hush Puppies on the stage lip for a suspenseful moment…and [making] Rasputin-penetrating eye contact with both Nena and me while trying on one of the wreathing smiles I’ve read about in Dickens.” Yes, at times, his extravagance of imagination kicks itself free of solemn clarity — but the effect can be wonderful. This is what he says of a slightly stupid billionaire wallowing sentimentally in misguided grief: “His trembling humanity had loosened the firm flesh from his skeleton, putting him in a permanent subsonic shiver where he seemed to be floating apart until an inspirational slogan or the recollection of some tremendous sum of money brought his electrons clustering back around their protons.” Extravagant, yes … but brilliant.

Osman’s similes are especially funny, again because they combine shrewd observation with startling inventiveness. Thus, for example, he describes his mother, dressed in South Asian garb, “looking as calm as a retired actress or culinary-adventure author or Merchant Ivory screenwriter being photographed for a 1980s magazine profile that would teem with words like matrician and doyenne.” Likewise, he says of a reception room: it “looked like it had been stone-by-stone rebuilt from some empire-raping Scottish industrialist’s ascetic-aesthetic retirement humility chamber.”

This kind of writing is fun. Very good fun. At the same time, though, Ruthnum clearly wants to document language that is far from fun — however funny. Few novels anywhere are written with such overpoweringly long chunks of dialogue. This is not because, unquestionably, Ruthnum doesn’t know how to write fast-paced interchanges. Yet he absolutely wants to get down, in hypnotizingly gripping detail, how language can be weaponized. Above all, this is the language of the “pitch” — a word that itself occurs repeatedly throughout the novel. In the corporate world especially, this language can draw on boardroom jargon as much as on self-help or Oprah-inflected gobbledegook. Whether a public pitch or private pitch, it hardly matters. Even in a backwoods racist church, language rolls relentlessly out of the mouths of the adept, casting its paralyzing spell over its — apparently — helpless victims.

Some of what Ruthnum exudes is recognizable jargon — words like “nano-influencers,” “front load,” expressions like “you’re part of generating this take” or “[I] thought you’d appreciate being onboarded face-to-face.” Even comparatively benign characters, like Nena, when on the job, can wield the rhetoric. When sent out to make a “pitch” to a potential investor, the ridiculously rich and ridiculously young entrepreneur, preposterously called Brody Beagle, she seductively emits a “flow of babble emerging from a combination of meditation apps and organic Adderall simulators.” Her ploy works. Brody is caught. [In case you’re wondering, Adderall is an ADHD medication].

As important as the language itself is the psychological spell-casting of the adept. Grimly nailing down the effectiveness of someone making a pitch to potential clients by using the “right shallow dips into shame and corporate self-interrogation,” Osman adds that this is “crucial sales and motivation tool.” Rather than summarize or even analyze many of these long speeches, though, Ruthnam reports them, paragraph after paragraph, page after page. Readers cannot help but be pulled into the spell of rhetoric even while, simultaneously, feeling not just amused, but also repelled. Olivia Robinson, first as she ascends to power and later, as she wields her power, is the real star in the firmament of this kind of language use. Even her private address to Osman goes on for pages, simultaneously drawing on both the language of compliment and the tactics of dismemberment.

In fact, one of the qualities of this kind of corporate world rhetoric that seems most to fascinate the author is the way it can pull simultaneously in two opposite directions. This is particularly the case as those wielding the rhetoric assume the position of penetrating the personality of their victim. Whether Nena is entrapping Brody, or Olivia is dismantling Osman, this kind of audacious faux intimacy is, in Rusnam’s hands, deliciously awful. Says Olivia to Osman, “You’re moulting. You’re becoming. It’s beautiful and it’s painful. I think you’re currently seeking out permission to step out of the identity your parents designed for you…” Up to a point, this tactic works. As Osman later confides, “there was nothing I loved better than being told who I am.”

Quite apart from the numbing power of this kind of rhetoric, naturally, is the underlying duplicity. In fact, closely paralleling what Ruthnam does with language is what he does with the recurring, relentless double-faced dealings of “our time.” Whether inside the corporate world or outside it, the author’s characters are phoneys. Even Nena Zadeh-Brot, generally sympathetic, has concocted a fake name because “it sounded old-world, and pan-cultural and unplaceable.” In her sales pitch to Brody, she tells lie after (often absurd) lie, including a hilarious version of her victimization at the hands of Iranian censors. Vikram Chandra, a wheel-chair-bound colleague, as ambitious for power as many others, likewise invents a fake past, spreading rumours of a “childhood slum disease.” Ajit, Osman’s father, invented an entire past, a “flux between India and Pakistan in his origins that eventually became a place of his own invention.” Ajit even tried to enlist the help of his son to write a “fake memoir.” As Osman puts it at one point, “Everyone lies” — even, as it turns out, his own, wonderful, mother. And, as he tells Brody, “Every single company you’ve made is a bullshit invention….Your talent is making people want to believe that you can’t possibly be as stupid as you seem.” Appropriately, in “our time” the biggest liar, Olivia Robinson, is also the biggest success.

What makes such duplicity so dangerous is its blood bond with cutthroat savagery. To remind ourselves that Ruthnam has his finger very much on the pulse of current mores in this regard, we need but consider the huge fascination with shows like Succession, its audiences like small jungle birds hypnotized by the serpents intent on devouring them. From the beginning the air tastes of danger. In his description of the novel’s first company meeting he writes, “The tremor of a hijack in progress passed through the room….” Soon to follow is the clinical excision of one victim after another from “AAP,” the edutech company on which the plot is settled. A character called Lottie writes a threatening email, behind which “wasn’t just the soon-to-be-annihilated Elodie Chan, or Halloran’s flaking authority, but the board, the true seats of AAP power” — true power, that is, “before Olivia’s ascent.” Calmly, Osman adds, “Lottie would be given her exit package before December.” And so it goes, from one meeting, speech, and email to the next: the positions of power submerge and emerge as the manoeuvres and counter-manoeuvres produce one victor, one victim after another. This decorous slaughter goes on in an atmosphere of many-headed fear. It can be the “harvesting” of computer files by the IT department or the explicit treatment of “new hires”: “it’s our pleasure to teach them fear.” The turtlenecked muscular thugs that hustle an inconvenient speaker off stage at Olivia’s biggest public meeting are only the most physical example of what goes on everywhere.

And it gets worse. When fear begets fear, racism will have its say. Having previously eschewed the “Curry” novel, Ruthnam here handles the topic head on. From the outset, there is clearly something askew: Osman kicks off the novel by performing (operative word) for some confused conference colleagues an anecdote in which he has been racially targeted by air force security. In no time (the very white) Olivia dismantles his story. What about the fact that he wields power, she says, through the “menace” generated by his brown skin?

Lest, though, we think that the novel is going to expose bold-faced racism, Ruthnam has Olivia apologize, and, almost simultaneously, ride on the coattails of the whole company’s “perfect diversity statistics.” At first, in fact, it seems that Osman’s sense of racism is mostly ironic, especially as he exposes the fatuously liberal embrace of oblique racism. At one point he tells us, “Neither of Lottie’s races were [sic] marginalized enough to help her survive her contract renewal period.” For Osman, the joke is on the laughably misinformed attitudes of those who prize “digestible exoticism.” Brody, for example, enjoyed in immigrants “tales of oppression left behind, of the humble glory of work, told in a light comfortably American tone with an occasional accented proper name glowing with desert warmth.” And, to make matters worse, the racialized members of AAP generally accept the racism: Osman observes Nena “assuming the correct degree of servility…the silent demands of being a darkie working for Olivia Robinson.”

If the matter were to stop here, the racism in the novel would serve chiefly to expose just another kink in the twisted values of corporate culture. Ruthnum makes sure it doesn’t stop there: on the contrary, as the plot accelerates, it reveals darker and darker currents of racism feeding into a whole ideology of white supremacy. First, it takes the form of a rant in a church service. A member of the congregation — Olivia’s father, importantly — invokes the need for those with superior intelligence “to continue building His Kingdom on the sewage-sodden foundation of this earth.” Worse, though, it penetrates the whole company that Olivia heads. In one of the most deliciously awful scenes in the book, Olivia tries, almost successfully, to seduce Osman to confess being a secret Muslim. Later, though, Osman, characteristically, refuses to see the incident as anything other than funny: “Before she could effect the first forced Islamic conversion by the secret owner [Olivia] of a backwoods Washington church,” she is interrupted and is forced, with satisfying bathos, to discuss “seating arrangements.” In public, she speaks of her company’s power to “uplift” all minorities, including “people of colour,” but Osman’s irony is undiminished: “She gave me a second of serious thought about embracing Allah.”

It is a toss up whether Ruthnum more reviles racism within the corporate world or the threatened debasement in colleges of the most foundational principles of humanism. While the racism is largely indirect, the declared purpose of the company that drives the plot is not: the purpose of “AAP” is the monetization of liberal arts education to the point of its being nothing more than business and, to boot, e-business — more, some readers might grimly observe, than it already is. The arrival of the Covid pandemic may, for some readers, confuse Ruthnum’s main satiric point, at least to the extent that much education, college education included, has been forced to become virtual. In his novel, the author acknowledges this effect of the pandemic, even showing how Osman goes into lockdown. However, the point remains the same. Traditional colleges are, in futuristic newspeak, to be replaced by “a college-disruptor that will deliver constantly updating curricula and personal interface with subject experts to a base of subscriptions….”

What makes Osman a “hero of our time,” though, is the fact that, instead of defying this threat, he chooses to work in the company that pushes it and, indeed, become wealthy on its back. Rather than leaving the critique of this business model implicit, though, Ruthnam makes sure the critique is explicit. Thus, Osman’s father, now dead (symbolically enough), becomes the spokesman for the novel’s most acrid analysis of “our time.” What we face now, according to Osman’s father (and, we surmise, Ruthnam), we can blame on “the market, on the techno-capitalist savagery that turned society away from the liberal arts, on the sprawling might and size of the administrative divisions, on the influx of money from other shores and the dominance of the financial ideals that had turned [our] Socratic grove into an educational-industrial complex.”

It says a lot about the kind of impact that this novel makes, though, that not Ajit, but Osman, is our hero. Instead of providing us a manual for saving the world with clear goals, Ruthnam puts us in the company of a man who filters the experiences of his times in such a way that we are left with a powerful sense of both it darkest shadows, and, in the end especially, coinciding with Osman’s thoughtful departure from it, its patches of light.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Visit his website here. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Rowena Rae, Kamal Al-Solaylee, Bruce Baugh, Rahela Nayebzadah, Genki Ferguson, Keath Fraser, and Matthew Soules. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1439 The language of the pitch”