1635 Depending on memory

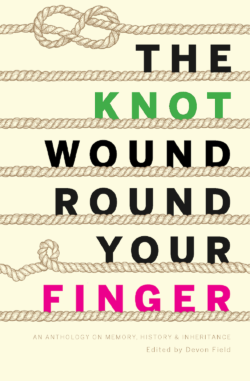

The Knot Wound Round Your Finger: An Anthology of Memory, History, & Inheritance

by Devon Field (editor)

Vancouver: Bell Press Books, 2021

$20.00 / 9780994812728

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

In a short story called “Lethe’s Share,” author Carsten Schmitt writes, “It’s our memories who make us who we are. “ Most of us would agree. Schmitt, one of the writers represented in a recent anthology, adds, “When we pass them on we live on.” The second claim is a little more tenuous than the first, and a little less universally felt. Still, the sense of reflection and, possibly, urgency in the joint statements lies at the heart of this entire collection.

In a short story called “Lethe’s Share,” author Carsten Schmitt writes, “It’s our memories who make us who we are. “ Most of us would agree. Schmitt, one of the writers represented in a recent anthology, adds, “When we pass them on we live on.” The second claim is a little more tenuous than the first, and a little less universally felt. Still, the sense of reflection and, possibly, urgency in the joint statements lies at the heart of this entire collection.

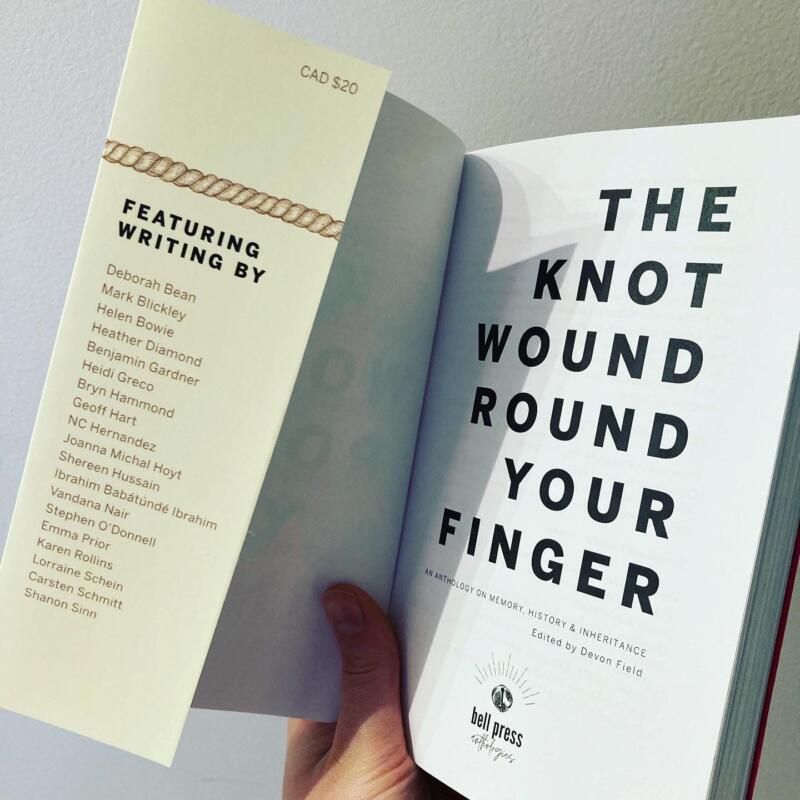

Editor Devon Field, teacher of “smallish children” in Vancouver, and “writer, podcaster and storyteller,” has collected nineteen short pieces in an anthology he calls The Knot Wound Round Your Finger. While some are labelled as fiction, some as nonfiction and some as creative nonfiction (in practice, the distinction blurs), all, according to the subtitle of the book, bear on at least one of “memory, history and inheritance.” In his short introduction to the volume, Field singles out memory as paramount: “how we preserve it and hand it down, how we use or distort it, and how it informs who we are both socially and individually….”

The two linked genres, memoir and autobiography are, of course, utterly dependent on memory. It is almost as difficult to imagine fiction not interlaced with the past, so interlaced in fact that most readers don’t give a second thought to the nature of the past unless explicitly steered in that direction. Arguably, at the very epicentre of nearly all of these kinds of writing (and, to boot, drama) is Proust’s monumental work of combined autobiography and fiction, À La Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time.) Indeed, virtually every field of thought, from history, psychology, anthropology, through to economics, and even sciences from astrophysics to evolutionary biology and medicine, depend on “remembering” the past to allow us to approach understanding the present.

Given the overwhelming number of materials from which Field could have selected, what he has chosen clearly bears the imprint of his personal vision both of the subject matter itself and of the ways of expressing it. In those terms, it reveals a lot that he has selected writers from a range of countries, almost half from the U.S and several from Canada, most of them still building their careers. Likewise, it reveals much that he has chosen works that (in nearly all cases), only touch on the nature of memory itself rather than delving into it extensively. In addition, the pieces cover a broad range of writing styles, from sharply focused details in a “naturalistic” mode, to nearly the opposite, challenging and dense pieces little concerned with the surfaces of reality (“Ill Spirits” by Bryn Hammond, for example, is a visionary, non-linear evocation of shamanistic healing). To all of his chosen authors, though, Field makes clear he feels a strong personal connection, to the point, in fact, that he says, almost startlingly, “I could not be more proud of them.”

What Field has done in this anthology, therefore, is allow the traditions and conventions of both fiction and memoir to breath freely through a wide range of short writing. In some of the pieces, the author’s connection with the past is confident and unblinking. Past events can be mined at will. “Snow Sled” by Deborah Bean, for example, is a simple but vivid piece of memoir about the author’s experiences of coping with two very small children in a very cold, very snowy Winnipeg. The piece depends on memory, but is not about memory. In an entirely different vein, but with an equally confident, unproblematic, hold on past events, Heidi Greco in “A Letter to My Left Arm” reflects on her experiences with vaccines, colouring them with social history by evoking her childhood experience of the polio epidemic and “the summer of that long-ago semi-lockdown.” Again, the writing depends on memory without being concerned with examining how it works.

“The Library,” a memoir by Ibrahim Babátúndé, makes many of the same assumptions about present writing and past events but with a slight twist. After introducing the piece by saying his memories of secondary school are “vague like a framed picture clouded by layers of dust,” the author then affirms that the incident he recalls is crystal clear, one of those “experiences raw enough to still tune your feelings … flashes that take you back to the exact emotions that shaped those particular moments.” The framework of the present then disappears: the readers experience an incident from the author’s past as a kind of present. The past, in this way, becomes a narrative present. The author virtually says as much as he ends the piece, “So much awaited me today….”

This kind of airy, untroubled way of collecting his materials is implicit in Field’s choice of title. After all, the conventional associations of a knot tied around a finger is as a reminder to undertake a minor task (Tuesday morning is garbage day!). None of these pieces plays on those associations. However, the knot in this title is not tied around a finger, but “wound round” it. What might be made of that is broadly suggestive, so broad in fact, that it serves well as an evocation of loosely associated diverse pieces.

Even so, a few elements recur in echoing the theme. The most iconic and evocative of these, perhaps, is the photograph. The very first selection in the book, in fact, is a memoir by Emma Prior called “A Photograph of My Mother.” As the single object around which the story of her mother crystallizes, the photograph provokes moving reflections on family interconnectedness across generations: “… is it me I see, or perhaps even my own daughter? The three of us held together. We will share what history we have, and the future is a journey we will take together.” In Carsten Schmitt’s “Lethe’s Share,” a science fiction story about transplanting (if that is the right word) an entire identity from one failing body to a younger one, the speaker is deeply frustrated by his lack of a photograph to anchor an important memory. In fact, the very title, with its allusion to the river of forgetfulness at the entrance to Hades, makes the point with or without the lost photographs.

Equally strong is exactly this kind of forgetfulness driven not just by time, but also by other circumstances, some internal, some external. A short story called “Photographs and Memories,” by Geoff Hart, is a harrowing first person account of progressive Alzheimer’s Disease — though, as the author points out in an end note, the reader has to accept the paradoxical assumption that the speaker is recalling his inability to recall. A memoir, “The Suitcase,” by Heather Diamond, provides another, more universal perhaps, take on this loss of a personal, remembered past linked to filmed images. In her terms, she imagines the past as film and is saddened because “another reel, one I have often tried and failed to conjure, remains hazy and full of questions.” Her sorrow and confusion are palpable.

Two of these pieces clearly employ not just the photograph as a touchstone of broad human experience, but also lament another nearly universal issue, the quicksands of memory. One of the most nuanced pieces in this book is a memoir by NC Hernandez called “Violence in the Calm.” Here, the attempt to rediscover a piece of family history is undermined by two different factors. The first appears in the form of those relatives who remain mute, fiercely unwilling to dig up the past. The second, though, occurs in the author’s complex reaction to two versions of the event he has been trying to recover. His confession demonstrates how memory can be not just passively faulty, but actively faulty: “I felt myself invested in Ernesto’s version of events…forgiving any obvious biases, and understanding that memory is a fluid thing that drains through our minds and into our bodies, that it never really washes away, it just changes form.” Having made the point, the author doesn’t linger on the issue. Its resonance is left merely to colour the rest of the piece.

A third, universally experienced phenomenon associated with memory, the chance trigger, achieves striking effect in two of the pieces, though the effect is primarily emotive. In Karen Rollins’ memoir, “That Day in my Bedroom,” the author confesses, “Sometimes when I hear songs like ‘Cinnamon Girl’ by Neil Young … I am even transported back.” This, surprisingly, is just about the only instance of anything approaching nostalgia in the whole book, and even then, when the author’s “memories depart… what lingers is a touch of regret and sadness.” The triggering event in a (very) short story called “Tea Break,” by Shereen Hussain, is a chance reading of a massive corporate bailout given to the East India Company. In this case the speaker’s memory connects with a particular tea party — and a sequence of a memories, on the surface purely linked to a family outing to the zoo, but, importantly, with dim but powerful hints of atrocities under the British occupation of India.

The combination of a personal event and broad political realities in Hussain’s story is comparatively rare in these pieces. Centred primarily on personal experiences, the recollections of past events do occasionally, though, provide a bridge to evocations of the historical forces identified in the book’s subtitle. For Heather Diamond, in “The Suitcase,” it is, first, Mao’s army and her father’s almost naïve association with them, and, second, the “pogroms in Ukraine.” In one of the most stirring pieces of writing in the book, a short story called “The Signature,” author Vandana Nair makes the whole impact of her story depend on the fact that, as a young woman, she ardently read “female idols” and, significantly, “felt like setting the world on fire…. ” The story of her frustrated attempts to infuse three young girls with the desire for emancipation from traditional expectations of early marriage is underscored by the sense she implants early in the story the fact that “India was still recovering from the brutal assassination of Indira Ghandi….”

Even more cogently, Mark Blickley, in a powerful essay called “Horizontal Recruiters,” comes to the harrowing realization that, as he feels, the entire U.S. military establishment is using public memorials with the most invidious of intentions. Thus, Arlington Cemetery is not, as he sees it, about the past at all. Instead, this vast “historical monument has become … a huge recruitment center rooted in the glorious mysteries of ancient legends of death and sacrifice.” Grotesquely, as Blickley sees it, “It’s the theme-park brainchild of the Pentagon that serves a future much more adroitly than the past it claims to represent.” In an ironic and perverse way, then, a bloody national past becomes twisted into something ensuring an equally bloody national future.

Shanon Sinn, in an extremely short piece called “The Elder Tree,” makes this connection between memory and vast forces at work in the world to an entirely different level. In his vision, a giant, ancient tree, a “god to forty-three different plant species, hundreds who lived in relationship with him even now,” in crashing ultimately to earth, does so “For all eternity.”

In an anthology as diverse as this, it is customary to say that there is something in it for everyone. While this is no doubt true, the real value of the book is, surely, to function as a reminder that it is almost impossible to imagine a corner of the human experience, channelled into any imaginable form of writing, where the past and our links to it, conscious or unconscious, are not part of our lives.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at the University of Victoria. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Pirjo Raits, Vince Ditrich, Madeline Sonik, Alex Rose, Frances Peck, and Naben Ruthnum for The British Columbia Review. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1635 Depending on memory”