1535 An English chambermaid

Queasy: a wannabe writer’s bumpy journey through England in the ’70s

by Madeline Sonik

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2022

$20.00 / 9781772141894

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

“There be dragons,” warn words in the corners of some old maps. The warning is really, of course, an invitation both to the intrepid to investigate remote lands and to the rest of us to listen, fascinated, to what the travellers have to report back. Madeline Sonik’s Queasy achieves much of its impact simply because it, too, documents what happens to a stranger in a strange land. However, instead of depending on the experiences of a well-prepared expedition to an exotic land, it relies on exactly the opposite elements.

“There be dragons,” warn words in the corners of some old maps. The warning is really, of course, an invitation both to the intrepid to investigate remote lands and to the rest of us to listen, fascinated, to what the travellers have to report back. Madeline Sonik’s Queasy achieves much of its impact simply because it, too, documents what happens to a stranger in a strange land. However, instead of depending on the experiences of a well-prepared expedition to an exotic land, it relies on exactly the opposite elements.

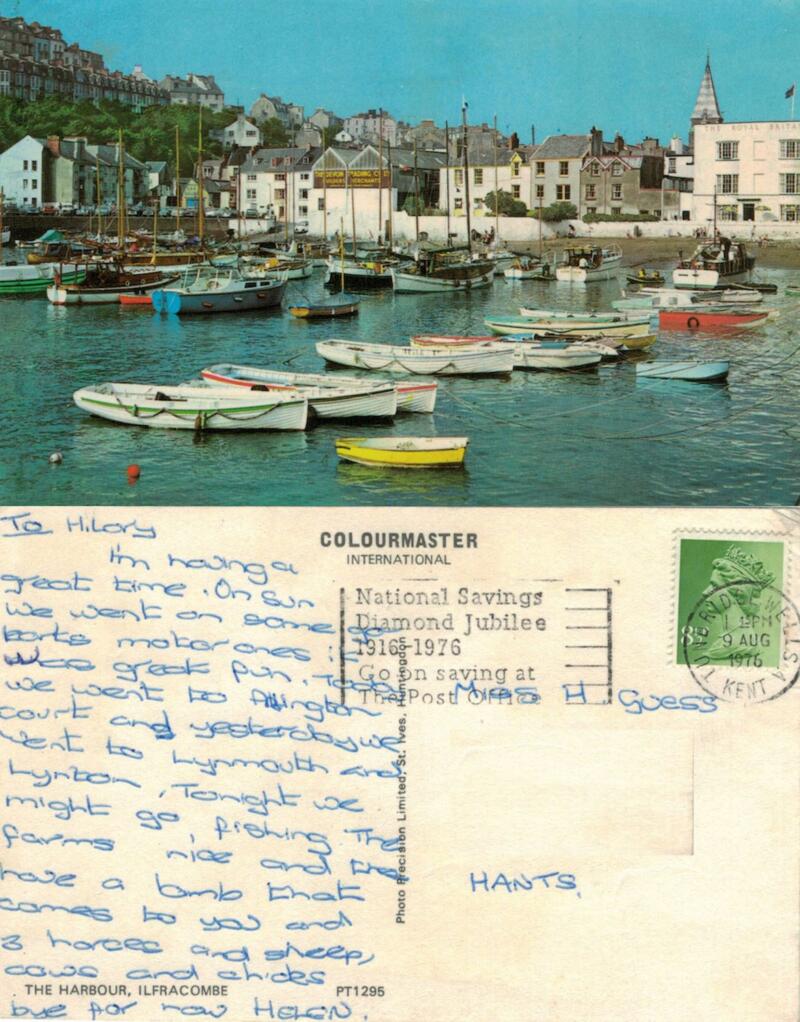

At the time of the venture she records, the author was an utterly naïve, poorly educated Canadian teenager finding herself, largely passively, in probably the least exotic location one can imagine outside Canada — the England of tea drinkers and pub goers, waitresses and chambermaids. The subtitle of the book, “A Wannabe Writer’s Bumpy Journey Through the England of the 70’s”, does, admittedly, take at least a couple of steps toward something a little out of the ordinary — the book centres on, first, a developing writer, second it deals with “bumpy” encounters, and, third, it witnesses the England of the seventies.

Even given these three angles, however, the average reader might feel a little hesitant to expect much from a teenaged girl from Windsor, Ontario trailing in the coattails of her English-born-and-raised, widowed mother. Clearly, however, Sonik has considered carefully the impact that can be achieved by focusing on her teenage experiences while also taking the book far beyond the callow understanding of her teenaged self.

In fact, she uses the very limitations of her younger self as a strategy. She repeatedly insists she was unburdened by any historical or political awareness (she calls herself a high school “dropout”) and further demarcates her role in England by insisting, unguardedly, that she is “apolitical” and never reads newspapers. Because, on the other hand, Sonik writes with the vastly expanded knowledge of her adult self, she can seamlessly integrate into her writing rich veins of social and cultural analysis. Very quickly the reader gets used to phrases like, “I didn’t know then that” or even “This was well before anyone realized that.” Assertions like, “I know nothing of the history of food controls in this country. Nothing of price boards and commissions or of the 1973 Counter Inflation Act,” become part of the very flow of the writing.

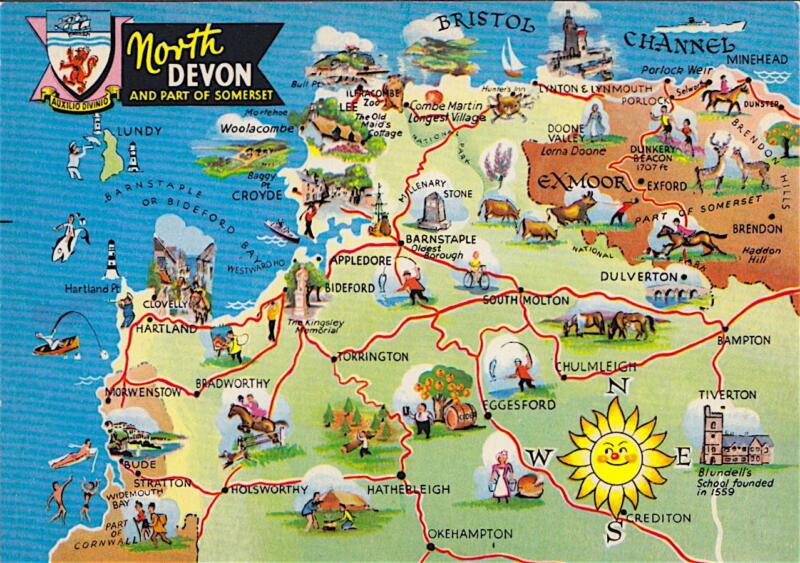

Partly what makes the research materials that the adult Sonik brings to the book particularly interesting is their variety. Especially towards the beginning of the book, she does a very busy trade in the “who wudda thunk?” market. Who wudda thunk, for example, as she records in a piece called “Shriek,” that at one time it was popular to own large, tropical “cats,” leading in one bizarre case to several of these animals (having grown inconveniently large and dangerous) being released onto the wilds of Exmoor, there to wreak exactly the kind of havoc their owners should have expected. Fascinating.

An additional kind of information imported into the book depends on the inherent interest of striking socioeconomic realities. Thus, for example, as the author records, “there are many ills in Britain this year. Approximately 1.4 million are unemployed and that number climbs daily. The Labour government, in an effort to control inflation, refuses to melt a pay freeze it has imposed on the public sector, and consequently the public sector moves in mad revolt.” Details follow on the effects of strikes by garbage collectors, hospital workers, and, most hair-raisingly, gravediggers. Again, fascinating.

A third kind of meta- information is perhaps most closely linked to the author’s own life. Indeed, in one of the chapters, called “Strange Customs,” the author, as a naïve observer, becomes the vehicle by which her adult self goes beyond mere information about England into what becomes something close to social critique: “What I didn’t know yet, but was in the process of learning, was that the mores and institutions of England were so completely different from those I’d left behind that there would forever be places inaccessible to me….” We get the message.

In fact, such is the breadth and range of Sonik’s interests, that she goes far, far beyond the “70’s” in evoking the ocean of social and cultural facts around the tiny island of her ignorant teenaged self: from the perspective of a much expanded time and place, her brutal experience with sexual assault, for example, forms the kernel of perspectives stretching from Victorian attitudes towards rape right up to the contemporary #MeToo movement.

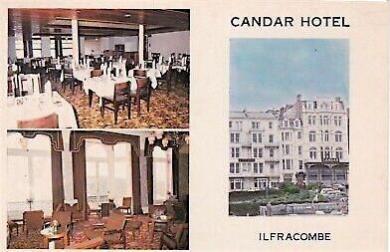

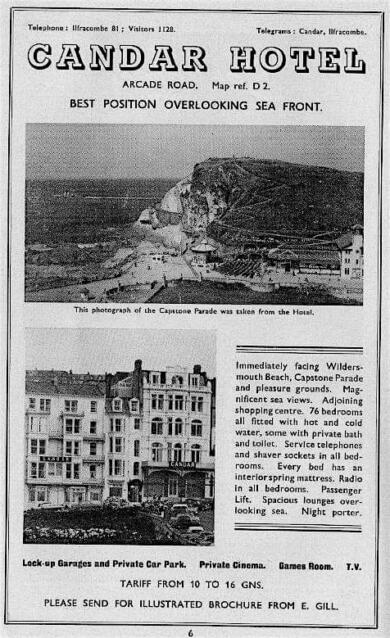

Apart from using these tactics to give her book depth and range, Sonik crafts each of the twenty-three pieces that make up the book, what the cover blurb describes as “a series of linked memoirs.” Typically, each piece begins with sharply focused details, placing the reader in a vividly recreated present. The piece called “Char,” for example, starts with the cleaning of a bathroom: “I kneel before a toilet, shake in some blue, bleachy crystals and plunge a rag deep inside…” Quickly, however, the writer provides a segue (she is a dab hand at providing segues): “I’ve not always thought of cleaning this way.” The next few lines provide (and repeat from early chapters) necessary autobiographical information to allow the subsequent events to unfold: “When I lived in Canada, before my father died and my mother moved us to England, before I needed to get a job and landed this one as a chambermaid at the Candar Hotel….” and so on.

To a large extent, this pattern is the carry over of the fact that the chapters were originally published separately in several journals, but the effect is to provide a distinctive tonal and discursive rhythm. Writing of the events in each of three jobs mostly in the present tense, she further develops most chapters by toggling back and forth between these past events and one (or two) distinct lines of explication and analysis (again, often with deft segues.) In one case, for example, she describes smoking and chatting with a fellow worker, while interleaving these passages with information on the tobacco industry during and well after the seventies.

A larger, overall unifying pattern is the roughly linear flow of time. The author’s particular family circumstances that land her in England form a narrative foundation for the recollections of three successive jobs, first as a waitress in one hotel, second as a cleaner in a second hotel, and third as a cleaner and “domestic” in a rural boarding school. At the core of the book is the way Sonik ensures that the girl’s experiences in her three jobs come alive. While she taps into many different dramatic elements to charge the narrative, arguably three provide the most punch: spleen, sentiment — and supernatural derrings do, ghosts included.

The stories of crises and characters in the two hotels where she works are awash with acrimony on the one hand and, on the other, genuine fellow feeling. As for the ghoulies and ghosties, not only does the author report scenes of her young self fumbling her way anxiously through many Tarot readings, but, as she says, “Virtually every hotel in Ilfracombe [and, it seems, nearby residential school] boasts a resident phantom.”

Far from sticking scrupulously to verisimilitude, or suggesting that her memory might be wobbly, the author launches confidently into recreating scenes — and, to add to the colour, local accents:

“The gaffer’ll’av to temporarily close,” Lilian says.

“You can’t run a ‘otel wifout a chef,” another waitress, Janice, concurs.

“Wot about me wages?” Ann asks.

The vividness of many such scenes, in fact, trades in much less in on the sepia hues of the memoir than the full colour of cinematic lens.

To add to the impact of the young girl’s experiences, Sonik recreates a memorable cast of characters — starting with her own family. The author’s mother, with whom she recalls fighting tooth and nail, not only demands that her daughter turn over all her meagre wages, but also rails about Canada: “Whenever the occasion arose to extol the superiority of England and denigrate Canada, she seized it.” Her uncle, likewise larger than life, is almost Dickensian in the range of imposters’ roles he cheerfully dons.

Even more Dickensian, though, are some of author’s fellow workers. There is Chris, the chef, vile-tempered and dictatorial at one turn, avuncular at another, and deeply treacherous at another. Cynthia Power, the grotesquely snobbish and imperious housekeeper, possibly deranged, is his counterpart in the school residence. Most memorable, most documented, and most loved, though is Mrs Dewell, demanding, strong willed, and good-hearted, the author’s smoking partner and (up to a point) confidant. Trumping them all, though, at least in one important regard, if not in colour, are two people Sonik meets at a writers’ workshop, almost the end goal of her working in England, and almost the climax of the book — Judith, who is a confident and “empowered” journalist, and, even more noteworthy, the famous poet Ted Hughes who is, indeed … Ted Hughes.

A further quality of Sonik’s writing arises less from the way she responds, through memory, to what she experienced (or recreates) than from the fact that, clearly, she loves writing — the rush and sound of language, its ability to build cadences and work images. Largely measured for much of the book, the tone tightens with irony at some points, lifts with barely restrained anger at others, but, most memorably perhaps, at some points sings:

Through pale-crossed windows, the frozen, blinding world bleats. It cries for us to see the newness it anticipates: its fine paper smoothness, its sparkle, a million microscopic stars. All the tracks we made the night before, all of our constructions, buried. The owl-like wind has swept the land, grasping yesterday in talons, erasing its existence.

This love of “creative” writing, even within a book of non-fiction, produces some of the most purely enjoyable reading in those chapters which stand out for their particularly distinctive brio. In one memorable chapter, Sonik segues between metaphors and speeches of military assaults on the one hand, with, on the other, mock-heroic depictions of cleaning: “When confronted with a chamber pot’s excrement submersible floating beneath a yellow urine sea, we rarely cowered, we rarely quaked.” The mock-heroic energy, amazingly, is sustained throughout the whole chapter.

One piece, called “Doggerel and Dirigibles,” is a kind of jeu d’esprit of creative ingenuity, inspired, amongst other things, by the fact that apparently rhymed verse went through a period of enormous popularity early in the century, to the point that in one place at least “tombstone doggerel was banned from its cemeteries.” Written, inventively, in the second person (addressed to her immediate superior, the dynamic and bumptious “Mrs Newell”), the piece largely toggles back and forth between Mrs. Newell’s battle-inflected rhetoric to clean, clean, clean and, strange to say, facts surrounding the history of hydrogen filled airships. Even more energetic and colourful, though, is the playful and deliberately outrageous rhymes that calculatedly disfigure the very sentences: “But airships filled with hydrogen, continued to sail the skies, despite the many disasters, despite the many carbonized. In the year you were born, Mrs. Newall, Wikipedia claims there were accidents three, though this web-source is not always accurate, and not often cited by me” (bolds not in original). And, yes, the whole chapter is written like this.

On a much darker note, a piece called “Expressions of the Unutterable” recreates the harrowing experiences of Ann and Angelina, the author’s great grandmother and great great grandmother, both oppressed, both alcoholic. Along with facts and figures about alcohol and alcoholism, the author experiments with a kind of past-and-present bridge-writing, neither pretending that she knows exactly what happened, nor allowing the past to be blurred by its very pastness. The result is writing threaded through with expressions like “In my mind’s eye, I see” or “Little Fred, I imagine, passes out with Ann’s [alcohol soaked] handkerchief still in his mouth, and Ann and Angelina continue to drink.”

Perhaps most important for the book’s effectiveness as a conduit into the vortex of culture and politics that surrounded a single, feeling sensibility, the teenaged author, is the way the author presents herself. In this regard she treads a careful, sensitively-gauged path. Where some writers might use the opportunity of a book like this to write exhaustively and exhaustingly about their every emotional quiver, and to explain and expand on the nature of their emotional and psychological lives, Sonik gives enough to deepen the readers’ empathetic understanding without swamping the writing with introspection and self-analysis. Even the most harrowing incident, involving sexual assault, works through painful and intense writing, but also shading. For many years after the incident, as she writes, “I’ll continue constructing my own defences and won’t think of Chris [the assaulter] again, until three years after I move back to Canada….”

Thus the book creates an affecting portrait of a young woman awakening to the world as much as to herself. Her helpless addiction to smoking, though it clearly scars her memories, becomes more the extension of the raw circumstances of her life than the occasion for self-loathing or self-defence. At times she lets slip terms like “introvert” to describe herself, or rues, almost lightly, her “crazy antics of defence.” When, however, she is told by a boyfriend that he likes her because she is “tough,” she reflects that her toughness (unlike, she notes, Margaret Thatcher’s “metallic kind”) is “only an uncommonly durable and crusty shell that houses a bundle of quivering adolescent insecurities, just as tooth enamel and pulp house raw nerve.” In a way, while it is good to hear the young Sonik reflect this way about herself, it is not absolutely necessary that she do so: the writing has exactly the sense of honesty and clear-sighted humility that it creates in itself a strong sense of both her vulnerability and her special brand of strength.

The reference to Margaret Thatcher here (the woman is frequently invoked in the book), and, a little earlier, to Ann and Angelina, are significantly related to what is probably the strongest thread of ideas in the book. On the dedication page, Sonik writes, “This book is dedicated to all the strong, positive, female role models who’ve encouraged me to follow my dreams.” As the book moves forward in time, through the sequence of her three jobs, and ends in the writers’ workshop, so, too, two other patterns emerge. First, the tone of the writing increasingly darkens. Second, it becomes increasingly centred on women’s issues — misogyny, sexual assault, and patriarchal abuse. It is in the last part of the book that she attempts to come to terms with the feminist movement, still only shadowy to her young self. Still, she reports, bitterly, “From all I’ve learned through observation and personal experience it is better for a woman to be dead than despised by men.” As for her desire to become a writer, or, indeed, anything else, as she discovers, “Sexism … is like a concrete wall across the highways of accomplishment.”

Yet also powerful — and this is at the life-giving core of the book — has been the author’s love of writing:

… professional writing as a career goal had materialized like a life preserver tossed on a vast and unpredictable sea. It would be years before I heard Joseph Campbell’s edict “follow your bliss,” but in those months before leaving school and immigrating to England, I’d discovered something that I loved doing and had enough of an instinct to pursue.

Indeed, if there is a reflexive impact of the book, it is, of course, that it is — like the author’s many other books (and, indeed, literary prizes) — a vindication and expression of itself. Specifically, though, as a work of memory, for many readers, perhaps the most poignant and powerful impact of the book is created by her thoughts as she watches a YouTube video of the school where she worked go up in flames. “As I … think of my own days there, I imagine [the owner at the time] in its emptiness, remembering the past, yet blinded, as we all are, to the bright and smoky spirits who haunt the future.” This statement, like the book itself, is a moving reflection on time, self, who we were and who we become, even how we fade into the future.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Alex Rose, Frances Peck, Naben Ruthnum, Rowena Rae, Kamal Al-Solaylee, and Bruce Baugh. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1535 An English chambermaid”

Most Intriguing