1445 One-way ticket to Anyox

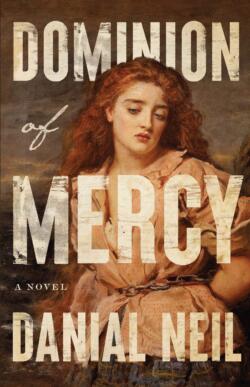

Dominion of Mercy

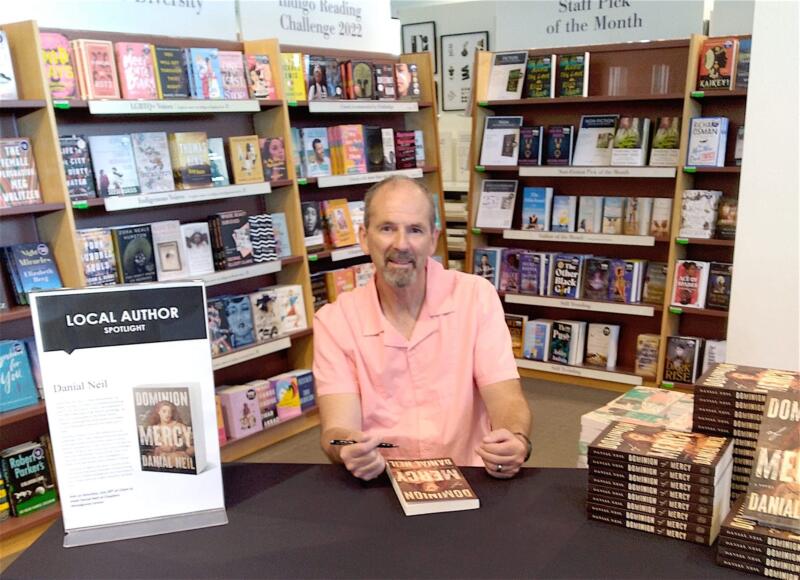

by Danial Neil

Edmonton: NeWest Press, 2021

$20.95 / 9781774390207

Reviewed by Zoe McKenna

*

Danial Neil’s Dominion of Mercy details a journey across continents and across centuries. Though the events of the novel are firmly set in 1917, few British Columbians will be unable to stop themselves from drawing parallels between locations as they know them today and their historical depictions in the novel.

Danial Neil’s Dominion of Mercy details a journey across continents and across centuries. Though the events of the novel are firmly set in 1917, few British Columbians will be unable to stop themselves from drawing parallels between locations as they know them today and their historical depictions in the novel.

Born in New Westminster, Danial Neil has been writing since his early teens and later studied creative writing at UBC. As a result, he boasts a prolific output of fiction, short stories, and award-winning poetry.

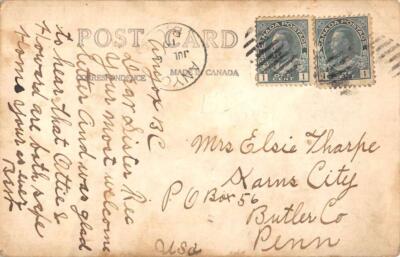

Dominion of Mercy, Neil’s fifth novel, begins in a police station in Scotland in 1917. As the First World War wages on, Mary Stewart, only eighteen years old, is being charged for prostitution. As the oldest child, Mary turned to sex work in order to provide for her younger sister and her father, who is unable to work due to an old injury. Mary’s uncle, a politician with little consideration for his family, is distressed by how Mary’s actions could reflect poorly on his professional relationships. In order to eliminate her potentially damaging influence, Mary’s uncle facilitates a place for her in a nursing program in Edinburgh, where she is to train until she is ready for work at the far-away mining town of Anyox, at the head of Observatory Inlet on the mainland coast north of Prince Rupert.

Though Mary sees through the facade of her uncle’s kindness, she accepts his one-way ticket to Anyox as a means by which to leave her work in the sex trade behind. Before Mary can leave her hometown, she is confronted by Jimmy, the violent man who acts as her pimp and controls her interactions with the men in the area. When this altercation gets out of hand, Mary is forced to make a decision that will follow her everywhere, even as far as the small company town no one in Scotland has ever heard of.

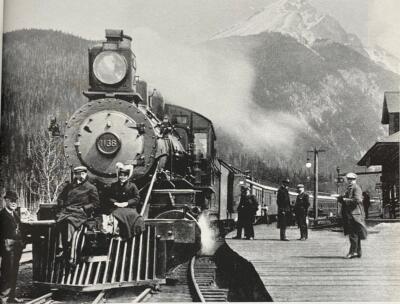

The novel progresses with impressive speed. Between life in Old Town, training in Edinburgh, the boat across the Atlantic, the train across Canada, and life in Anyox, the novel’s backdrop changes with startling frequency, especially in the first half of the book. This fast-paced progression serves to convey the placelessness that Mary experiences in her first weeks away from her home and loved ones. Though the protagonist is far too head-strong to admit these anxieties, Neil captures the feeling splendidly. The focus of the novel seems to shift with each new location, as Mary contends with leaving her life and family in Scotland, removing herself from the dangerous life of prostitution, learning a new trade, and familiarizing herself with a strange style of community in a country completely unfamiliar to her. Despite these numerous topics and locations, the novel manages to remain clear and focused. The plot is never muddy, because Mary leads her way though the novel with such confidence that it feels impossible to question what comes next.

Like many women protagonists from Canadian frontier novels, Mary is bold and cheeky as a means to survive. Her spunky nature gives her a charm that is difficult to resist — though plenty of characters try, with strict reprimands and stern warnings. While her sharp tongue often gets her into trouble and her actions are far from angelic, her flair for the dramatic and commitment to speaking her mind position Mary as a unique and endearing protagonist. Her attitudes towards political or social tensions in the early 20th-century are forward-thinking, enough that modern-day audiences can engage with her mindset, but not so much so that the protagonist feels at odds with her novel.

Balance between the appeal to a 21st-century audience while honouring the historical accuracy of the novel becomes a notable theme throughout. Set in a real-life company-owned former mining town, Neil situates the novel firmly in time and place. As Mary familiarizes herself with the strange mannerisms of the locals and the confusing layout of the town, so too are readers brought along for a discovery of what once was a hub of north coast economy and activity. Those in search of a historical drama with a rich plot and interesting characters will be pleased with Dominion of Mercy. Further, those history buffs with a passion for local heritage and intricate details will be enamoured with the level of historical framework Neil deftly includes.

My one reservation is the noticeably scant depiction of Indigenous people and communities. Mary does question the presence of an Indigenous man in one scene, asking another character, Goose, about “the man on the boat.” Mary goes on to recall seeing Indigenous people in the prairies during her train travel across Canada, noting that “it seemed … they had a question.” Goose tells Mary that on the prairie, the question is “what was happening to their land,” while in Anyox, the question is when the settlers will be leaving. While the mention of Indigenous peoples and the impact colonization had on their relationships to their land and culture are not absent from the novel, the conversation between Goose and Mary nevertheless ends with Mary thinking to herself that “it seemed [the Indigenous man] did not exist at all, but an apparition, perhaps appealing for the past to return.” The topic is not revisited, so in this way, despite Mary and Goose’s exchange, the novel contributes to the historical and ongoing erasure of Indigenous people, culture, and issues in Canadian fiction — all the more disappointing when considered against the careful attention to historical detail elsewhere in the novel.

Dominion of Mercy is a remarkable piece of travel fiction as well as a thoughtful tribute to British Columbian history. Though Mary’s story is neatly concluded as the story closes, readers may find themselves yearning to know more about their own local mining towns. Well-structured and propulsive, Dominion of Mercy invites contemplation into the unique stories, people, and places that made British Columbia what it is today.

*

Zoe McKenna recently completed her Master of Arts from the University of Victoria and also holds a Bachelor of Arts from Vancouver Island University. Her thesis, as well as a great deal of her other reading and writing, focuses on horror writing in Canada, especially that by BIPOC authors. Her previous work has appeared in VIU’s Portal Magazine and the Quill & Quire. When not reading, writing, or reviewing, Zoe can be found hiking a local mountain or in front of a movie with her two cats, Florence and Delilah. She is always covered in cat hair and wears almost exclusively dark clothing to prove it. Find her here on Twitter. Editor’s note: Zoe McKenna has recently reviewed books by Allie McFarfand, Chevy Stevens, Carmella Gray-Cosgrove, Ed O’Loughlin, Meghan Bell, Genni Gunn, and Penny Chamberlain for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1445 One-way ticket to Anyox”