1232 Unwelcome in the academy

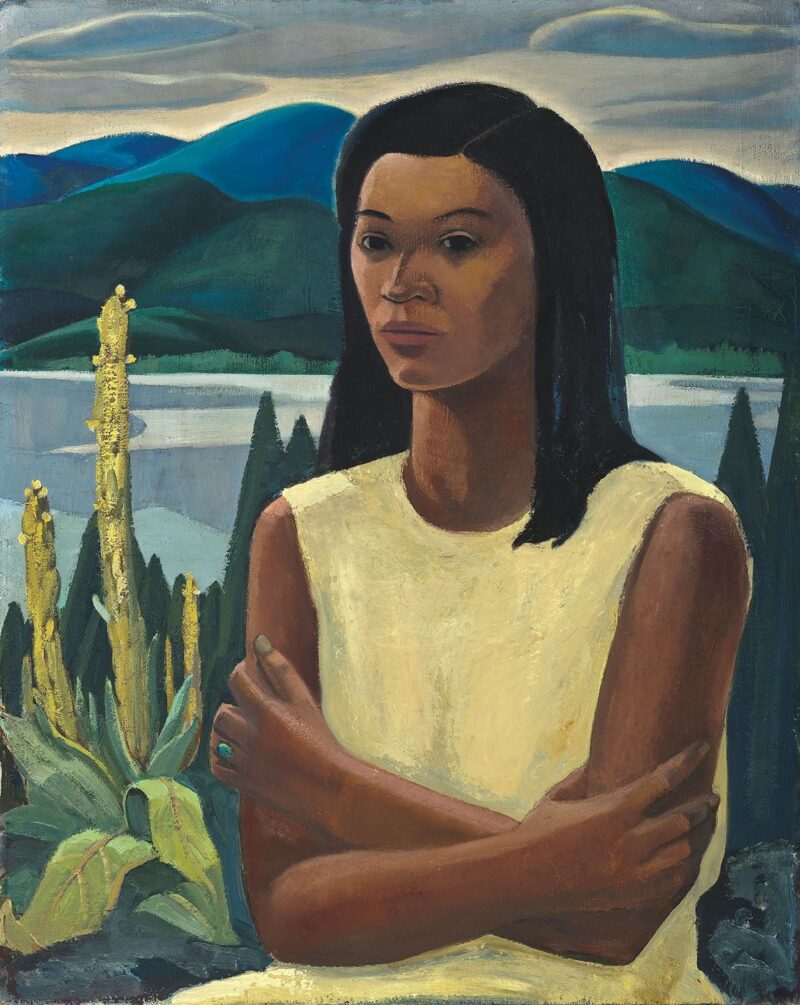

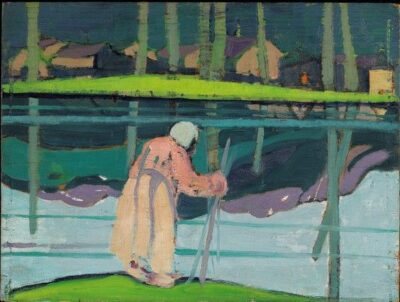

Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Moment

by Sarah Milroy (editor)

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2021, in collaboration with The McMichael Canadian Art Collection,

Kleinburg, Ontario

$60.00 / 9781773271194

Reviewed by Maria Tippett

*

Today, we all accept that historically Canadian female artists were excluded from major exhibitions and art societies, given little financial support compared to their male contemporaries, and produced their work under difficult circumstances. Even after the so-called feminist revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, women artists continued to receive less remuneration for their work whether it was sold in private galleries or put on the auction block. They were awarded fewer grants and private and public commissions. And their work rarely appeared alongside their male contemporaries. In books from Mayo Graham’s ground-breaking Some Canadian Women Artists (National Gallery of Canada, 1975) to my own By a Lady, celebrating three centuries of art by Canadian women (Penguin, 1992) and, more recently, Concordia University-based Canadian Women Artists History Initiative, there have been attempts to redress the balance.

Thus, Uninvited, Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement is yet another step, in the words of the book’s editor Sarah Milroy, towards helping “Canadians to experience at last the irrefutable evidence of women’s contribution to the visual arts in the modern period, from coast to coast to coast, and the value of women’s insight more generally — their ability to see what their male counterparts were less equipped or inclined to see, and to make their art from a place of deep humanity, curiosity, and intelligence” (p. 22).

One of the most effective ways of subsidizing the publication of a coffee-table book on Canadian art is to mount an exhibition at one of the country’s major art galleries. This promises generous corporate and government funding and sales in gallery gift shops. It ensures that the catalogue accompanying the work on display will be well-illustrated and that all the scholars and curators who provide the text will have an opportunity to flex their learned muscles — Uninvited has no fewer than forty contributors.

As the editor of the book under review and curator of a forthcoming exhibition hosted by the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, Sarah Milroy and her colleagues can congratulate themselves on having produced a handsome tome. Even so, if readers expect to be introduced through the book and the exhibition to a representative group of female artists who produced work from the late nineteenth century to the end of the Second World War, they might be disappointed. This is because Uninvited is dominated by artists from central Canada, among whom are Pegi Nicol MacLeod, Paraskeva Clark, Frances Loring, Florence Wylie, Elizabeth Wyn Wood, Yvonne McKague Housser, Bess Harris, among others — all of whom have received previous attention.

Emily Carr and Vera Weatherbie represent British Columbia’s contribution, with no place found for the modernist sculptor Beatrice Lennie or the Post-Impressionist painter Statira Frame. Maritime artists, with the exception of Elizabeth Styring Nutt, fare little better. Likewise, Mabel Killam Day, Elizabeth Cann and Marjorie Tozer deserve to have been included, while the omission of the African-Canadian artist Edith Hester McDonald-Brown (1886-1954) is also to be regretted. As for the representation of those female artists who lived and worked in Quebec, surely Francine Gauthier, Irène Sénécal, and Marie-Cécile Bouchard could have been given at least a walk-on part, alongside the Quebec-based Anglo-Canadian artists who are included in the book like Anne Savage, Marian Dale Scott, Emily Coonan, Prudence Heward, and Lilias Torrance Newton.

Whether living in Quebec, Ontario or British Columbia the majority of the artists Milroy has singled out for attention have one thing in common: that they came within the ambit of the Ontario Group of Seven, either as lovers, pupils, disciples or fellow exhibitors. By contrast, the majority of those who did not come under the Group of Seven’s influence were Indigenous and Inuit artists. The Coast Salish artist Sewinchelwet (Sophie Frank) is represented by an exquisite coiled cedar-root storage basket, alongside other Indigenous and Inuit artists who produced beaded, quilled and woven work. But their non-modernist work seems out of sync in a book whose subtitle is Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement just as much as that of the Mi’kmag male artist Jordan Bennett, whose Tepkik that was installed at Toronto’s Brookfield Place in 2018. Alternatively, if Milroy’s remit extended to Inuit and Indigenous artists, should she not have included female ceramic artists and quilt-makers?

Such inconsistencies seem unnecessary. Perhaps it is high time for scholars and curators to exhibit and produce histories that celebrate female artists alongside their male contemporaries. I confess that my own work on Canadian sculpture has served to persuade me that female artists are more than capable of holding their own alongside their male colleagues. Perhaps it is time that we allowed them to do so in the books that we write and in the exhibitions that we curate.

*

Maria Tippett spent the formative years of her academic career as sessional lecturer at Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Following her year as Robarts professor of Canadian studies at York University (1986–7), she lectured in South America, Europe, and Asia and curated exhibitions. In 1991, she returned to academe, becoming a member of the Faculty of History at Cambridge University and a senior research fellow and tutor at Churchill College, also at Cambridge. Since her formal retirement in 2004, she has written four books, including Sculpture in Canada: A History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2017), reviewed here by Catherine Nutting. Among many awards, in 1980 she won the Sir John A. Macdonald Prize for her path-breaking Emily Carr: A Biography (Oxford University Press, 1979), which also won the Governor General’s Award for non-fiction. Editor’s note: Maria Tippett has also reviewed books by Laura Bradbury & Rebecca Wellman (with Peter Clarke), Kaija Pepper, Mary Fox, Ruth Abernethy, and Roger Boulet for The Ormsby Review, and she has contributed a memoir, “HRH: A nodding acquaintance.”

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1232 Unwelcome in the academy”