1275 The making of an art collector

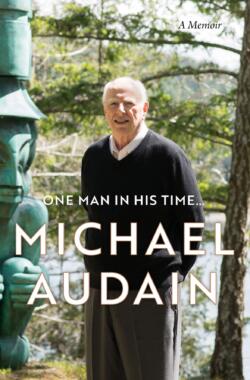

One Man in His Time… A Memoir

by Michael Audain

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2021

$36.95 / 9781771623001

Reviewed by Maria Tippett

*

No conventional memoir, One Man in his time. . . allows Michael Audain to roll out his life story in a randomly selected collection of “tales” and “anecdotes” that resemble fireside chats (p. 259). This pick-and-choose method begins with cameo portraits of Audain’s school teachers, most of whom administered “mandatory beatings” on a regular basis (p. 10) “Jimmy” Audain was no less eager to punish his son. A leather slipper, a dog whip, a belt and occasionally a clenched fist were favoured weapons. The beatings continued until his boxing trainer at the Victoria City Police gym, noting the welts on the fourteen-year-old’s bottom, contacted the police. The beatings stopped.

No conventional memoir, One Man in his time. . . allows Michael Audain to roll out his life story in a randomly selected collection of “tales” and “anecdotes” that resemble fireside chats (p. 259). This pick-and-choose method begins with cameo portraits of Audain’s school teachers, most of whom administered “mandatory beatings” on a regular basis (p. 10) “Jimmy” Audain was no less eager to punish his son. A leather slipper, a dog whip, a belt and occasionally a clenched fist were favoured weapons. The beatings continued until his boxing trainer at the Victoria City Police gym, noting the welts on the fourteen-year-old’s bottom, contacted the police. The beatings stopped.

No wonder the boy was miserable during the formative years of his life or that the only sport in which he excelled was boxing. Had Michael Audain been born into the Dunsmuir family during the last half of the nineteenth century, at a time when his great-great-grandfather Robert Dunsmuir and his son James “built a family dynasty that sprinkled the Vancouver Island landscape with coal mines, railroads and castles,” things might have been different (p. xii). Even so, though Michael’s grandfather Colonel Guy Audain had spent most of Sara Byrd Dunsmuir’s fortune, there was enough money left in a trust fund to send young Michael, born in Bournemouth, England, in 1937, to private schools in Great Britain and, following his family’s move back to British Columbia in 1947, in Victoria and Toronto.

During most of his life, Michael Audain took pains to avoid identifying himself with the Dunsmuir family. In 1957 he trained as a commercial pilot in Normal Wells, just south of the Arctic Circle; but when CP Air lost its contract to supply goods to the DEW line, Audain returned to Vancouver where he resumed his studies at the University of British Columbia, where also he formed the Nuclear Disarmament Club in 1961. During one summer vacation he joined the Freedom Riders in the American south; sitting at the back of a bus and in the “coloured section” of a restaurant duly landed him in a Mississippi jail.

It was Audain’s commitment to civil liberties that brought him to the attention of the New Democratic Party. Though he had previously voted for the Conservative Party, he was invited in 1961 to be a delegate at the party’s inaugural convention in Ottawa. Now a committed supporter of the NDP’s new leader, Tommy Douglas, Audain returned to Vancouver where he completed Bachelor of Arts in 1962, a Bachelor of Social Work in 1963, then a Master’s degree in social work in 1965.

During this time Audain worked as a juvenile probation officer and as a social worker with the United Way in Vancouver’s East End. It was here that he saw how “much of the older housing was deteriorated and families lived in either overcrowded conditions or paid an exorbitant amount of their income for rent” (p. 135). Eager to learn more about how this problem might be solved, the thirty-year-old student enrolled in 1968 in the London School of Economics’ (LSE) Social Administration Department, headed by Richard Titmuss, whom many considered “the intellectual guru of the modern welfare state” (p. 135). Audain didn’t last long at LSE. His participation in student protests in London and in Paris overrode his commitment to academe, and by 1969 Audain was suddenly back in Canada.

It was a crucial decision to abandon his Ph.D. He thus moved from advocating socialized housing to overseeing actual housing projects, working first with the NDP and then with the private sector — the road to Audain’s future success. While Audain admits that he went into the property business at the right time, it was his ability to make connections with prominent actors in both the public and private sector, and to win their trust, that saw him become the most prominent home-builder in British Columbia.

It wasn’t always smooth sailing, as he duly hints. In the 1990s many people who had bought their wood-frame condominiums and townhouses from Polygon Properties Ltd. “lost their savings; others lost their homes, as in some cases they were forced to abandon them instead of face the remediation bills” (p. 224). Audain blames “the leaky condo crisis” on the NDP’s antipathy to business; also, on changes made during the 1980s to the National Building Code. Even so, Polygon continued to thrive. So did its chief executive.

Although it was Audain’s first partner, Tunya Swetleshnoff, who got him interested in art during the early 1960s, it was not until the turn of the century that Audain, along with his second wife, Yoshiko Karasawa, became a serious collector. They prudently chose blue-chip artists like British Columbia’s Emily Carr, the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, and Quebec’s Jean Paul Riopelle. And when the growing collection overwhelmed the walls of their West Vancouver home, the couple built their own gallery to house it. The Audain Art Museum opened in 2016 at the international ski resort in Whistler, some 120 kilometres north of Vancouver.

Audain’s success as a businessman and a philanthropist has earned him the Order of Canada, the Order of British Columbia, and membership on the board of the National Gallery of Canada. Now in the ninth decade of his life, he insists that he still has “many goals to pursue” before he meets his Creator. If this includes collecting more works of art in the twenty-first century, I hope that he can discover artists — both Indigenous and non-Indigenous — who have not already commanded the record-breaking prices of work created by such iconic figures of the last century’s Jean Paul Riopelle and Emily Carr.

*

Author of over fifteen books dealing with the cultural history of Canada, Maria Tippett spent the formative years of her academic career as sessional lecturer at Simon Fraser University, UBC, and the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Following her year as Robarts professor of Canadian studies at York University (1986–7), she lectured in South America, Europe, and Asia and curated exhibitions. In 1991, she returned to academe, becoming a member of the Faculty of History at Cambridge University and a senior research fellow and tutor at Churchill College, also at Cambridge. Her recent books include Sculpture in Canada: A History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2017), reviewed here by Catherine Nutting. Maria Tippett’s second collection of short stories, Art for Art’s Sake, will be published in 2022. Among many awards, in 1980 she won the Sir John A. Macdonald Prize for her path-breaking Emily Carr: A Biography (Oxford University Press, 1979), which also won the Governor General’s Award for non-fiction. Editor’s note: Maria Tippett has also reviewed books by Sarah Milroy, Laura Bradbury & Rebecca Wellman (with Peter Clarke), Kaija Pepper, Mary Fox, Ruth Abernethy, and Roger Boulet for The Ormsby Review, and she has contributed a memoir, “HRH: A nodding acquaintance.”

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1275 The making of an art collector”

Thank you for this intelligent review. Regarding the final sentence suggesting Mr. Audain only collects art by iconic painters for record-breaking prices, a close reading of the book would find he began collecting art by then-emerging BC painters bill bissett and Michael Morris as well as William Kurelek when he was still earning his living as a picture-framer. Through his foundation, Mr. Audain has continued to support emerging artists with contributions to art schools including Emily Carr University and by sponsoring many awards to emerging Canadian artists including such fine young talents as Pip Dryden, Carly Greene, Erick Jantzen, Homa Khosravi and Romi Kim. This and more information about Mr. Audain’s continued support to contemporary Canadian artists is readily available at https://audainprize.com/