#429 Trail, the bomb, and Blaylock

Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb

by Ron Verzuh

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018

$13.08 / 9781720820703

Reviewed by Michael Sasges

First published Nov. 22, 2018

*

Codename Project 9 is a small book that engenders reflections on some big history.

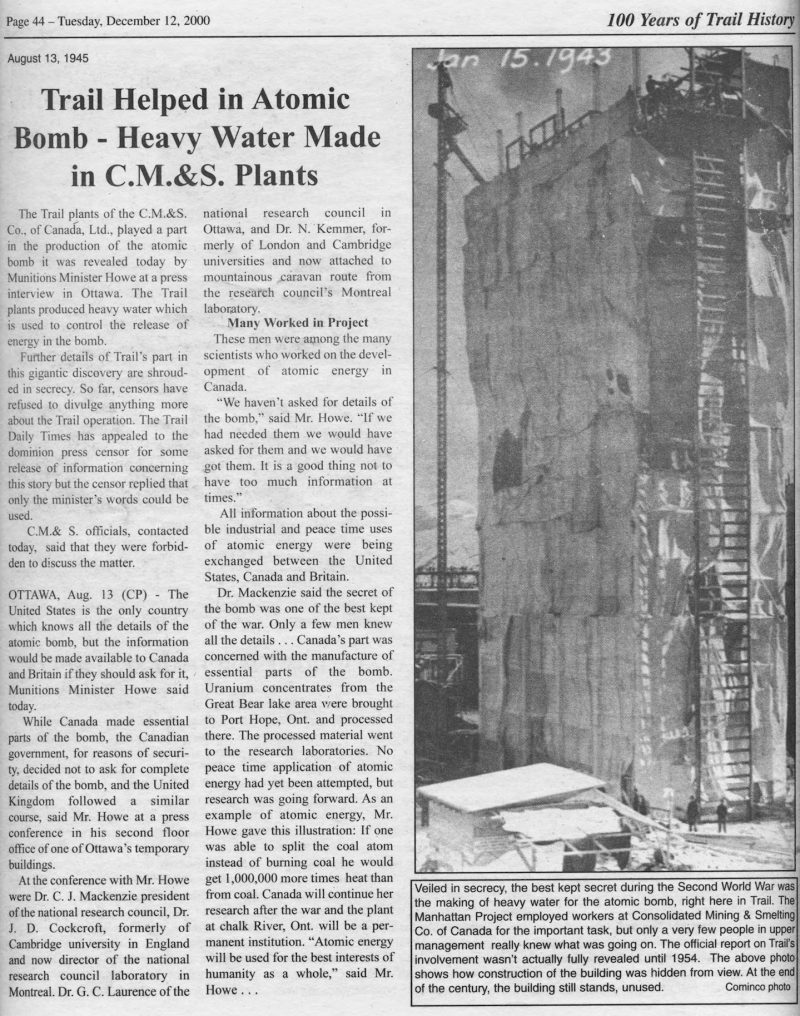

Since 1945, journalists and scholars have chronicled the midwifery contribution of Consolidated Mining and Smelting and the city of Trail to the nuclear age, a story sparked by the publication of a Trail Times report, seven days after Hiroshima and four after Nagasaki, under the headline “Trail Helped in Atomic Bomb.”

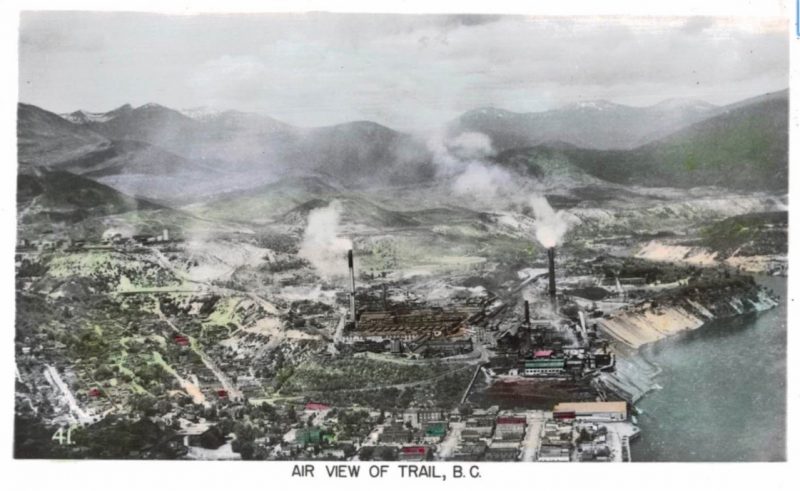

So why might the B.C. reading public generally and small-history buffs particularly want to know anew that between 1943 and 1955 a Teck Cominco predecessor produced heavy water in the West Kootenay for the U.S. war department and its Manhattan Project and for the Canadian government and its nuclear-reactor research? My answers are these:

Firstly, Codename Project 9 is exemplary summary history.

Historian Ron Verzuh ably incorporates what has been told and nicely advances it. His interviews, and those by others, are an especially important addition to the Project 9 story. Ordinary agency is always instrumental in executing extraordinary undertakings.

“We used to just cringe when we went in there,” a retired Consolidated Mining fireman who routinely inspected the sprinklers in the heavy-water production facility told Verzuh.

Secondly Codename Project 9 is an examination of a Manhattan Project anomaly, and anomalies inevitably advance appreciation and understanding.

The Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada (renamed Cominco in 1966) was the only Manhattan Project supplier located outside the United States. Further, neither the heavy water from Trail nor the heavy water from the three facilities located in U.S. was used to help make an atomic bomb. Project Manhattan military officers and scientists preferred another fission “moderator,” but invested in heavy-water production in case their preference turned out to be a dud. (It didn’t.)

Codename Project 9 was, in other words, a memorable local measure of the vigour of the American pursuit of the first weapons of mass destruction. (The American government spent almost $2 billion US in 1944 dollars on the Manhattan Project, the Brookings Institution estimated twenty years ago, including almost $27 million on four heavy-water plants.)

Thirdly, Project 9 is an opportunity to consider anew the management unto dismissal of the peripheral abilities and ambitions of British Columbia by Canada’s Laurentian metropolis.

The CPR, for example, had to approve the production contract between its subsidiary, Consolidated Mining and Smelting, and the U.S. war department.

And then the Canadian government located its nuclear-research efforts during and after the Second World War in central Canada, far, far, far from the heavy water in British Columbia. There are probably good Laurentian Ascendancy reasons for why the water went to Chalk River, and not Chalk River to the water, doubly so when the water was produced upriver from the pioneering Hanford facilities in Washington state.

On the proverbial other hand, Codename Project 9 meant that some admirably accomplished men lived and worked in the West Kootenay countryside in the years of the Second World War.

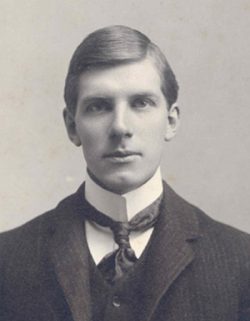

The federal government seconded three of them for nuclear-research work back East. The Consolidated Mining and Smelting executive who negotiated the U.S. war department contract epitomizes the commercially and scientifically astute man managing a vital wartime industry and making key decisions far, far removed from the metropolis. The Americans attempted to lowball Consolidated Mining and Smelting, but its chief executive, McGill-educated Selwyn Gwillym Blaylock (1879-1945), countered successfully.

Further, the Americans weren’t asking Consolidated Mining and Smelting to take on the production of an unknown product by an unknown production method. Blaylock knew about heavy water and could offer the Americans a production facility that they only had to modify, not build.

Perhaps Ron Verzuh might consider a biography of S.G. Blaylock for his next book.

*

Mike Sasges’ favourite trailering trip after retirement was a “WMD wander” that took him from Richland, Washington, where his wife’s American cousin resides, to Santa Fe, New Mexico — from Hanford to Los Alamos. A retired Vancouver newspaper editor and reporter, Mike has written two essays for The Ormsby Review, “From Quilchena Creek to Flanders” (#39, November 7th, 2016) and “Chief Tetlenitsa’s Apples: Commercializing Indigenous Horticulture in British Columbia, 1907-1916,” (#124, April 25th, 2017), as well as several recent book reviews. Mike Sasges has an MA in Graduate Liberal Studies at Simon Fraser University. He lives in Merritt.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

26 comments on “#429 Trail, the bomb, and Blaylock”

A Great publication.

Anton Wagner, Hiroshima Nagasaki Day Coalition, Toronto.

Comments are closed.