Race and class; magic and music

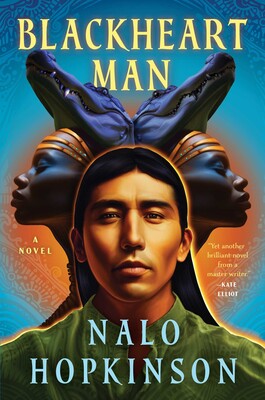

Blackheart Man

by Nalo Hopkinson

Toronto: Simon & Schuster / Saga Press, 2024

$34.99 / 9781668005101

Reviewed by Zoe McKenna

*

Nalo Hopkinson is a well-known name in science fiction and fantasy writing.

Born in Jamaica, Hopkinson lived in Guyana, Trinidad/Tobago, and the United States before moving to British Columbia, where she now teaches creative writing at UBC. The author of 15 books, including the award-winning Brown Girl in the Ring, Hopkinson is highly celebrated, with dozens of accolades to her name. Notably, she was the 2021 recipient of the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award, making her the youngest recipient of the award and the first woman writer of African descent.

Fifteen years in the making, Hopkinson’s latest novel, Blackheart Man, pushes the boundaries of just how much one story can hold.

Blackheart Man begins in the thick of the action. Veycosi, a student at the nearby Colloquium, has a knack for getting into trouble. Though decently smart and gifted, Veycosi is fame-hungry, always seeking new opportunities to be the centre of attention and admired by his community. He takes this to the extreme by coordinating a small explosion, meant to clear a blockage and return water to the city of Carenage, which ends up having a far greater impact than expected. To make matters worse, Veycosi had ‘borrowed’ a rare book from the Colloquium, which fell to the water in the chaos.

As if this opening isn’t frenzied enough, as Veycosi is detonating his homemade bomb, Chynchin is approached by a fleet of ships. The fleet belongs to Ymisen, a nation that once colonized Chynchin before a slave revolution supported by three witches set the island free. As punishment for his actions, and in the hopes that folk stories may hold the secret to keeping Chynchin a free nation, Veycosi is told to collect tales from the community about the magic that helped safeguard the island from Ymisen long ago.

Though sometimes charming and often witty, Veycosi is, at best, a challenging character. While his heart is occasionally in the right place, selfishness drives many of his actions. Rather than settling for a normal, reliable job his fiancés (Chynchin marriages are commonly between two men and a woman) have requested, Veycosi consistently finds himself in trouble. Veycosi can acknowledge his errors, but he struggles to shake the belief that he is meant for greater things than gathering stories about witchcraft. He’s often dismissive of the magical undercurrent that underpins Chynchin’s history (and the novel as a whole). His would-be stepdaughter, Kaïra, is said to be the next representative of the goddesses, and though Veycosi is outwardly encouraging, his support for Kaïra wavers depending on his own interests.

Despite its spirited opening, Blackheart Man can be slow going. At times, it has a pace that feels like moving through the thick piche (tar) that marks so much of the novel. There’s a lot to take in. The terminology, history, class politics, and setting are stunning—but also come together to form a very weighty novel. The weight is especially evident as subplots, flashbacks, and interjections from other narrators lead readers off the novel’s main path.

Though Veycosi is a difficult guide, it’s impossible to deny that the intricate world Hopkinson develops is breathtaking. Chynchin and the city of Carenage are beautiful, but more than that, offer a rich social and cultural landscape that investigates class relations, race, and gender in a largely matriarchal society. Paired with the broader historical and political milieu inherent to Chynchin’s relations with Ymisen, and pulling from real-world folk stories surrounding the Blackheart Man, every element of the novel’s world-building is as meticulous as it is expansive.

To add to the intricacy, the characters in the novel speak with a unique vocabulary that draws inspiration from Creole. Presented without explanation, readers encounter terms like piche and pickens (children) and must use context clues to understand their meaning. While having to pause to unravel the definitions of these terms can add to the novel’s complexity, the words are often easy to figure out and make reading the novel out loud (or listening to the audiobook) a treat. Before long, these new words become familiar and help to make the story even more immersive.

Blackheart Man goes beyond richness in its depth and detail—it’s decadent. As a result, it’s a novel best enjoyed in small bites. It would be easy to read Blackheart Man three or four times, focusing on different areas of the book on each read-through, before getting the full picture and understanding all of the commentaries and ideas Hopkinson has woven into the novel.

With that said, just because something is challenging doesn’t mean it isn’t worth working for. Blackheart Man is unlike any other novel, both in its interrogation of race, class, and politics and its celebration of music, magic, and friendship. It’s likely that every reader will take something different from the novel, and likelier still that they will return time and time again to unveil something new.

*

Zoe McKenna holds a MA from the UVic and a BA from VIU. Her thesis, as well as a great deal of her other reading and writing, focuses on horror writing in Canada, especially that by BIPOC authors. Her previous work has appeared in VIU’s Portal Magazine and Quill & Quire. When not reading, writing, or reviewing, Zoe can be found hiking a local mountain or in front of a movie with her two cats, Florence and Delilah. She is always covered in cat hair and wears almost exclusively dark clothing to prove it. Find her on Twitter. [Editor’s note: Zoe McKenna has reviewed books by Marcus Kliewer, Ivana Filipovich, Giselle Vriesen, Scott Alexander Howard, S.W. Mayse, Linda Cheng, Paul Cresey, Michelle Min Sterling, Eve Lazarus, David Wallace, David Ly & Daniel Zomparelli, Sophie Sullivan, kc dyer, Robyn Harding, and Lindsay Cameron for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Race and class; magic and music”