1947 Canadian mountain culture and mountaineering

ESSAY: Canadian Mountain Culture and Mountaineering

by Ron Dart

*

And sliding on the mountain snow, Dear Friend, we’ll let our worries go.

-Alexander Pushkin, “Winter Morning”

Great things are done when men and mountains meet; this is not done by jostling in the street.

-William Blake, Gnomic Verses

The sweetest thing in all my life has been longing—to reach the mountain, to find the place where all that beauty came from.

-C.S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces

Last night I had a curious dream about Kanchenjunga. I was looking at the mountain and it was pure white, absolutely pure, especially the peaks that lie to the west. And I saw the pure beauty of their shape and outline, all in white. And I heard a voice saying—or got the clear idea of: “There is another side to the mountain”

-Thomas Merton, The Asian Journal

There is a back story to Canadian mountain culture and mountaineering and it is an imperative to be told to have a sense and feel for the larger and more historic context. Such an unfolding drama is ably and nimbly told in Jim Ring’s must read beauty, How the English made the Alps (2000) and Max Amstutz’s The Golden Age of Alpine Ski-ing (2010). It was the accelerated interest by the English in the late 19th-early 20th centuries in Switzerland that developed and matured, to a higher level, Swiss mountain culture and mountaineering. There is one man and place which stands out more than most in this process: Sir Arnold Lunn (1888-1974) and Murren. I was fortunate in the early 1970s to live in Gimmelwald-Murren (returned in 2012) and equally fortunate to correspond with Lunn’s secretary, Elisabeth Hussey (1929-2017), before her death, Hussey’s Biography of Sir Arnold Lunn (2014) a key in the ignition read for yet a deeper and fuller context of the Anglo-Swiss-Canadian mountaineering tradition.

There is a back story to Canadian mountain culture and mountaineering and it is an imperative to be told to have a sense and feel for the larger and more historic context. Such an unfolding drama is ably and nimbly told in Jim Ring’s must read beauty, How the English made the Alps (2000) and Max Amstutz’s The Golden Age of Alpine Ski-ing (2010). It was the accelerated interest by the English in the late 19th-early 20th centuries in Switzerland that developed and matured, to a higher level, Swiss mountain culture and mountaineering. There is one man and place which stands out more than most in this process: Sir Arnold Lunn (1888-1974) and Murren. I was fortunate in the early 1970s to live in Gimmelwald-Murren (returned in 2012) and equally fortunate to correspond with Lunn’s secretary, Elisabeth Hussey (1929-2017), before her death, Hussey’s Biography of Sir Arnold Lunn (2014) a key in the ignition read for yet a deeper and fuller context of the Anglo-Swiss-Canadian mountaineering tradition.

I mention the above for the simple reason that the Swiss Guides played the leading role in developing mountain culture and mountaineering in Canada in the late 19th and up to the middle of the 20th century in the Rockies in Canada, the CPR the mode of getting those keen to the mountains both the transportation guide and builder of generous accommodations in Banff, Lake Louise, Glacier House at Rogers Pass and Mount Stephen House in Field. The CPR built a controversial and pseudo-Swiss village in Golden to house the guides and families and, at the present, there is a significant move to protect the historic village from developers. I have been fortunate, many times, to linger at Swiss Edelweiss Village and my wife and I were offered the opportunity to spend a night in one of the Feuz’s homes in Golden. But, to the story of Canadian mountain culture and mountaineering, Swiss Guides often given the dominant role, Austrian guides a secondary one.

The publication of In The Western Mountains: Early Mountaineering In British Columbia (1980) by Susan Leslie and a fuller approach, focused on the Swiss Guides in the Rockies, The Guiding Spirit (1986) by Kauffman-Putnam are must reads not only for an entrée into Canadian mountaineering culture and mountaineering but the role women such as Phyllis Munday and Georgia Engelhard (niece of the much acclaimed artist, Georgia 0’Keefe) played. The Wild Spirit: Woman in the Rocky Mountains of Canada (2009) is a superb walk into the essential role women have played both in mountain culture and mountaineering. The Swiss Guides do need their respectful nod as pioneers and guardians of mountain leadership in Canada and a more in depth approach is provided by D.L. Stephen’s Edward Feuz Jr.: A Story of Enchantment (2021). Many of the guiding trips by Feuz Jr. to multiple peaks, his pivotal role in the building of the Abbot Pass Hut (where I have spent many a generous night but now decommissioned) and many rescues are part of Canadian mountain lore and legend.

The publication of In The Western Mountains: Early Mountaineering In British Columbia (1980) by Susan Leslie and a fuller approach, focused on the Swiss Guides in the Rockies, The Guiding Spirit (1986) by Kauffman-Putnam are must reads not only for an entrée into Canadian mountaineering culture and mountaineering but the role women such as Phyllis Munday and Georgia Engelhard (niece of the much acclaimed artist, Georgia 0’Keefe) played. The Wild Spirit: Woman in the Rocky Mountains of Canada (2009) is a superb walk into the essential role women have played both in mountain culture and mountaineering. The Swiss Guides do need their respectful nod as pioneers and guardians of mountain leadership in Canada and a more in depth approach is provided by D.L. Stephen’s Edward Feuz Jr.: A Story of Enchantment (2021). Many of the guiding trips by Feuz Jr. to multiple peaks, his pivotal role in the building of the Abbot Pass Hut (where I have spent many a generous night but now decommissioned) and many rescues are part of Canadian mountain lore and legend.

There can be no doubt Swiss Guides were the dominant face of mountaineering in Canada in the early decades of the 20th century (a fine sculpted icon of sorts depicting such significance by the Chateau at Lake Louise as is their historic chalet), but many of their exploits and peaks bagged were not of the same demanding quality as the Austrian, Conrad Kain, Kain Hut in the Bugaboos a way of honouring his rare and high level mountain ascents. The autobiography of Kain, Where the Clouds Can Go (with forewords by such mountaineers as Monroe Thorington and Hans Gmoser and an updated foreword by Pat Morrow) is a must read for those interested in the life of a mountaineering vocation just as the more recent and tender letters between Kain and Amelie Malek, Conrad Kain: Letters from a Wandering Mountain Guide: 1906-1933 (edited and introduced by Zac Robinson) is a keeper not to miss, the mountaineering Kain meeting the more romantic Kain, Malek his inspiration. One of our finest Canadian poets, Earle Birney, penned Kain (although not of the same nuance as his classic David), the poem poignant and telling. The Kain sculpture in Banff’s Cascade Plaza is worth a visit. My short article “Conrad Kain and Lake O’Hara” (O’HARA 2013) reflected on Kain’s guiding the first Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) trip to Lake O’Hara in 1906.

There can be no doubt Swiss Guides were the dominant face of mountaineering in Canada in the early decades of the 20th century (a fine sculpted icon of sorts depicting such significance by the Chateau at Lake Louise as is their historic chalet), but many of their exploits and peaks bagged were not of the same demanding quality as the Austrian, Conrad Kain, Kain Hut in the Bugaboos a way of honouring his rare and high level mountain ascents. The autobiography of Kain, Where the Clouds Can Go (with forewords by such mountaineers as Monroe Thorington and Hans Gmoser and an updated foreword by Pat Morrow) is a must read for those interested in the life of a mountaineering vocation just as the more recent and tender letters between Kain and Amelie Malek, Conrad Kain: Letters from a Wandering Mountain Guide: 1906-1933 (edited and introduced by Zac Robinson) is a keeper not to miss, the mountaineering Kain meeting the more romantic Kain, Malek his inspiration. One of our finest Canadian poets, Earle Birney, penned Kain (although not of the same nuance as his classic David), the poem poignant and telling. The Kain sculpture in Banff’s Cascade Plaza is worth a visit. My short article “Conrad Kain and Lake O’Hara” (O’HARA 2013) reflected on Kain’s guiding the first Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) trip to Lake O’Hara in 1906.

I was fortunate that Roger Patillo lived in Abbotsford the final few years of his life (where I live) and his two tomes, most personal and insightful, on Lake Louise and Rocky Mountain life offer a glimpse into the era, people and places that are often missed or ignored in more formal and scholarly telling: Lake Louise at its Best: An Affectionate look at life at Lake Louise by one who knew it well and The Canadian Rockies: Pioneers, Legends and True Tales. Many were the meetings Roger and I had together as we lingered and lived through his beauties.

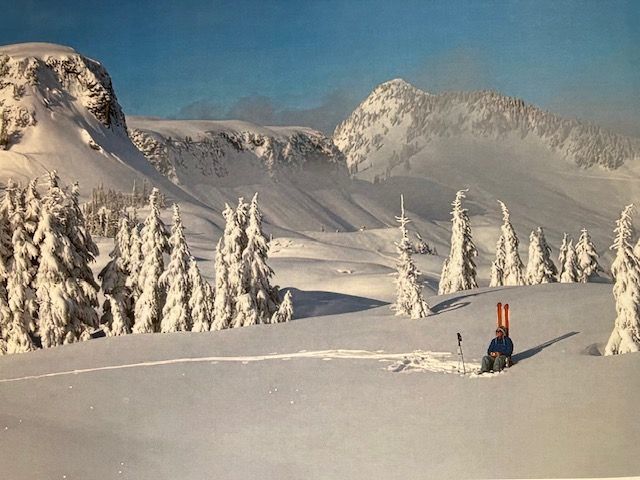

It was just a matter of time, of course, before the Swiss-Austrian and European mountaineering tradition and ethos would be replaced by a growing Canadian generation, alternate ways of taking to the mountains and newer treks in Canada and beyond the goals, hopes and dreams. I was fortunate in December of 1975 to do a five day ski touring trip to Assiniboine under a full noon, the small wooden cabins our fireplace warm sites to sleep. Then, in the March 1976, I did another ski touring trip into the Cathedral Lakes area in BC, almost at 7,000 feet by the lakes, slept in snow caves. I mention this for the simple reason that Swiss Guides and Conrad Kain did not focus or do serious ski touring. This is an area of winter mountaineering that has become a specialty in the last few decades and Powder Pioneers: Ski Stories from the Canadian Rockies and Columbia Mountains (2005) by Chic Scott and even more so John Baldwin’s Exploring the Coast Mountains on Skis (3rd edition) are imperatives to own and heed for those keen to take to the mountains in a way some of the earlier winter mountaineers never did at the same level of skill and ability. Needless to say, heli-skiing has yet further upped the cost of such touring and powder descents, another Austrian, Hans Gmoser, at the forefront (and others) in this area. Chic Scott is, without doubt, the leading historian of Canadian mountaineering and his biography of Gmoser, Deep Powder and Steep Rock: The Life of Hans Gmoser (2009) and his more comprehensive Pushing the Limits: The Story of Canadian Mountaineering (2000) reveals broad and layered historic vistas of the Canadian mountaineering journey.

The role of the Alpine Club of Canada, The Canadian Alpine Journal, extensive high alpine hut system, BC Mountaineering Club (BCMC), and the Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC (FMBC) have provided mature and skilled leadership in all season-all terrain mountain culture and life, Cloudburst the flagship magazine of FMBC. The Swiss Guides did, though, play necessary roles in training and building up the Canadian Search and Rescue ethos, Walter Perren at the forefront of such leadership, the tale told in memorable historic detail in Kathy Calvert’s and Dale Portman’s Guardians of the Peaks: Mountain Rescue in the Canadian Rockies and Columbia Mountains. It was Perren’s advanced training in Swiss mountain techniques that moved Canadian rescue abilities to a much higher level after the Second World War and into the 1960s, a new generation of Canadian guides and skilled rescue leaders, including Tim Auger, put Canada at the forefront of mountain rescue. The last time I met Tim was in Lake O’Hara, a trip I led up to Abbot Pass and other peaks in the area part of the guided circuit. Tim and I, at the time, had a lovely chat about the Canadian novelist, Sid Marty, both wardens for a time at O’Hara, Tim many an interesting tale to tell about Sid, Sid not at the higher levels of mountaineering skill of Tim.

The role of the Alpine Club of Canada, The Canadian Alpine Journal, extensive high alpine hut system, BC Mountaineering Club (BCMC), and the Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC (FMBC) have provided mature and skilled leadership in all season-all terrain mountain culture and life, Cloudburst the flagship magazine of FMBC. The Swiss Guides did, though, play necessary roles in training and building up the Canadian Search and Rescue ethos, Walter Perren at the forefront of such leadership, the tale told in memorable historic detail in Kathy Calvert’s and Dale Portman’s Guardians of the Peaks: Mountain Rescue in the Canadian Rockies and Columbia Mountains. It was Perren’s advanced training in Swiss mountain techniques that moved Canadian rescue abilities to a much higher level after the Second World War and into the 1960s, a new generation of Canadian guides and skilled rescue leaders, including Tim Auger, put Canada at the forefront of mountain rescue. The last time I met Tim was in Lake O’Hara, a trip I led up to Abbot Pass and other peaks in the area part of the guided circuit. Tim and I, at the time, had a lovely chat about the Canadian novelist, Sid Marty, both wardens for a time at O’Hara, Tim many an interesting tale to tell about Sid, Sid not at the higher levels of mountaineering skill of Tim.

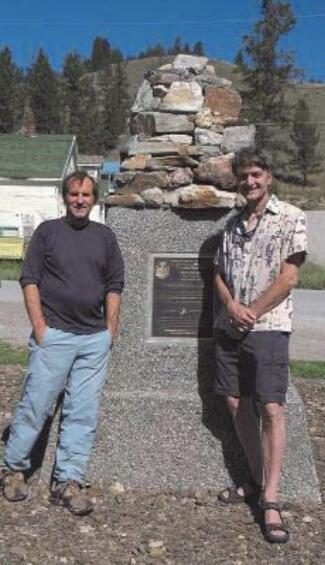

Certainly one of the most interesting and multi-gifted and wide ranging Swiss mountaineers of 2nd-3rd generation was Bruno Engler (1915-2001). Bruno was a renaissance mountaineer in many ways and his mountain journey took him into the military, films, photography, guiding, a bon vivant of sorts and a skier of the best level for his generation. The Bruno Engler Memorial Ski Race is Canada’s longest running ski race and Bruno’s Bar and Grill in Banff honours his life and lineage. The sheer breadth of mountain culture knowledge and creative, energetic mountaineering abilities of Engler did not endear him to the more conservative Swiss Guides or the more focused and demanding climbing exploits of Kain. But, an elementary read of Engler’s A Mountain Life: The Stories and Photographs of Bruno Engler (1996) makes for a most pleasurable read and walk into Canadian mountaineering culture and history. I have a certain fondness for Engler for the simple reason that when I returned from Switzerland in 1974, I lived in the Crowsnest Pass area from 1975-1977, and Engler lived there in the late 1940s-early 1950s, when there initiating all sorts of mountain leadership. My wife Karin and I met in the Crowsnest Pass and were married at the base of the first mountain we climbed together (Crowsnest Mountain). The layered mountain life of Engler does need to be on the top shelf in Canadian mountain lore and legend.

Many have been the Canadians who have climbed some of the more challenging peaks outside of Canada, also, Jim Haberl, for example K2 and Pat Morrow did the 8 Summits listed by Messner and Bass, Pat’s book, Beyond Everest: Quest for the 7 Summits (1986) a compelling must read—Pat, like Bruno Engler, a superb photographer. Jim Haberl’s two books, K2: Dreams and Reality (1994) and Risking Adventure: Mountaineering Journeys Around the World (1997) are worth many a read, the latter book dedicated to Sue Oakey. Sadly so, Jim was killed in a mountaineering accident, and Sue’s book, Finding Jim, threads together a layered and complex story (and the ambiguity of it). I was fortunate to correspond with one of the most significant mountaineers of the 20th century, Reinhold Messner, and his comments from a letter have a perennial truth to them. I had asked him about the films done on his life, books and articles written about him and the books-articles he has published—he said, in almost Zen like style, “Films are films, Life is life”. But, I turn again to Canadian mountain culture and such a mountaineering journey.

Many have been the Canadians who have climbed some of the more challenging peaks outside of Canada, also, Jim Haberl, for example K2 and Pat Morrow did the 8 Summits listed by Messner and Bass, Pat’s book, Beyond Everest: Quest for the 7 Summits (1986) a compelling must read—Pat, like Bruno Engler, a superb photographer. Jim Haberl’s two books, K2: Dreams and Reality (1994) and Risking Adventure: Mountaineering Journeys Around the World (1997) are worth many a read, the latter book dedicated to Sue Oakey. Sadly so, Jim was killed in a mountaineering accident, and Sue’s book, Finding Jim, threads together a layered and complex story (and the ambiguity of it). I was fortunate to correspond with one of the most significant mountaineers of the 20th century, Reinhold Messner, and his comments from a letter have a perennial truth to them. I had asked him about the films done on his life, books and articles written about him and the books-articles he has published—he said, in almost Zen like style, “Films are films, Life is life”. But, I turn again to Canadian mountain culture and such a mountaineering journey.

The Whyte Museum in Banff has one of the finest collections of Canadian mountaineering culture, mountaineering culture much broader and fuller than merely peak bagging, glacier treks, ice climbs and ski touring. The Whyte Museum was named after Peter and Catherine Whyte, both fine painters (connected to a generation of mountain painters) and front and centre in the mountaineering ethos of the Rockies as it emerged from its birthing through mature phases of greater and more refined skill development. The Whyte Museum and the lives of Peter-Catherine are essential to know in entering the growing mountaineering culture in the 20th century.

Many is the Haute Route worth the skiing in Europe, the Chamonix to Zermatt one of the charmers, but the Wapta Traverse in the Rockies (often called the “Haute Route of North America”) is a trip more than a delight to do both in summer and winter. A linger 7 days, four huts on the traverse, makes for some superb ridges and summits to crest, some short roping needed for a couple of the peaks. I must admit I have found the Wapta Traverse one of the most pleasant treks done in my many trips and treks in the mountains—certainly on par with many European haute route trips. The West Coast in the Whistler-Blackcomb region is in the process of creating another Canadian Haute Route—the Spearhead Traverse has been done many times, but when the 3 huts are finally finished (one already) the Spearhead Traverse will certainly hold high a significant challenge to the beauty of a Wapta Haute Route. I have mentioned the Wapta and Spearhead treks for the simple reason that many of the early generation of European and Canadian mountaineers did not have the privilege of approaching the mountains in such a way. Needless to say, such Haute Route trips are becoming more popular each year and throughout the year (winter touring trips and summer trekking trips).

Many is the Haute Route worth the skiing in Europe, the Chamonix to Zermatt one of the charmers, but the Wapta Traverse in the Rockies (often called the “Haute Route of North America”) is a trip more than a delight to do both in summer and winter. A linger 7 days, four huts on the traverse, makes for some superb ridges and summits to crest, some short roping needed for a couple of the peaks. I must admit I have found the Wapta Traverse one of the most pleasant treks done in my many trips and treks in the mountains—certainly on par with many European haute route trips. The West Coast in the Whistler-Blackcomb region is in the process of creating another Canadian Haute Route—the Spearhead Traverse has been done many times, but when the 3 huts are finally finished (one already) the Spearhead Traverse will certainly hold high a significant challenge to the beauty of a Wapta Haute Route. I have mentioned the Wapta and Spearhead treks for the simple reason that many of the early generation of European and Canadian mountaineers did not have the privilege of approaching the mountains in such a way. Needless to say, such Haute Route trips are becoming more popular each year and throughout the year (winter touring trips and summer trekking trips).

If longer and more spacious ski touring trips tended not to be on the agenda for pioneers in Canadian mountaineering neither was caving an interest to which they turned with interest or skill. Gratefully so, spelunking has become its own growing area of mountain skills the last few years. I lived in the Crownest Pass from 1975-1777 and led many trips into and through some of the often uncharted and unmapped caves at the time, many a night sleeping in large rock caverns, pack rats aplenty, wriggling through ice tunnels, entering the mountain from one entrance, looking down into valleys from the other side of the mountain. I was fortunate to be one of the last (a group of us from Chilliwack Outdoor Club) to squirm our way about the various chambers and tight spots of Nakimu Caves above Rogers Pass—easy to become claustrophobic in such a paper thin jagged rock place, Nakimu now considered unsafe.

Canadian mountaineering culture and mountaineering has come a long distance from the early days of the Swiss Guides, Conrad Kain and the CPR dominating transportation to the lower alpine regions. The growth of the interest in glaciology, the century long retreat of Illecilliwaet Glacier at Rogers Pass and Peyto Glacier in the Icefields has meant the issue of global warming and glacier melting and retreat is a canary in the mineshaft message not to miss. I have spent ample time at Wheeler-Asulkan Hut at Rogers Pass and the many trail treks to Illecilliwaet Glacier reveal a telling tale. The Wapta Traverse begins at Peyto Glacier and the trek up the glacier to the first hut reveals another glacier retreat. The fact Abbot Hut (once one the highest huts in Canada and built by the Swiss Guides) is now considered unsafe and dismantled reveals yet once again writing on the environmental wall not to miss. The Alpine Club of Canada and Parks Canada (do a read of Ted Hart’s J.P.Harkin: Father of Canada’s National Parks) did much, decades ahead of their time, to protect mountains, waters, forests and rivers from the ravages of corporations means. Increasingly so, mountaineering organizations and the federal government need, once again, to work together for a higher good for both the present and future generations.

montani semper liberi

Ron Dart

*

Appendix: Glacier Melt: Athabasca Glacier

I have enjoyed many a glacier and peak climb in the Rockies over the decades, Mt. Athabasca (11, 453) and Mt. Hector (11, 135) but a couple of the 11,000ers so aptly described in Bill Corbett’s (2004). Regretfully so, the last century has witnessed the slow and, more recent, retreat of many a glacier, Illecillewaet at Roger’s Pass a more moderate century long retreat, Peyto in the Icefield much faster and this past winter-summer Athabasca Glacier an accelerated retreat and melt, warmer winter and hot summer. When I trekked from Wheeler Hut to Asulkan Hut at Rogers Pass, then higher glaciers to local peaks (Jupiter Range in the area), it is from such ridges and peaks possible to see where Illecillewaet once was and has shrunken to. The same can be applied to Peyto Glacier, the trek up it to the hut and, for those keen and eager, the Wapta Traverse, looking back from the top of Peyto Glacier its melting. The first time I went up Peyto was in the mid-1970s and its frightening melt signals a canary message.

I have enjoyed many a glacier and peak climb in the Rockies over the decades, Mt. Athabasca (11, 453) and Mt. Hector (11, 135) but a couple of the 11,000ers so aptly described in Bill Corbett’s (2004). Regretfully so, the last century has witnessed the slow and, more recent, retreat of many a glacier, Illecillewaet at Roger’s Pass a more moderate century long retreat, Peyto in the Icefield much faster and this past winter-summer Athabasca Glacier an accelerated retreat and melt, warmer winter and hot summer. When I trekked from Wheeler Hut to Asulkan Hut at Rogers Pass, then higher glaciers to local peaks (Jupiter Range in the area), it is from such ridges and peaks possible to see where Illecillewaet once was and has shrunken to. The same can be applied to Peyto Glacier, the trek up it to the hut and, for those keen and eager, the Wapta Traverse, looking back from the top of Peyto Glacier its melting. The first time I went up Peyto was in the mid-1970s and its frightening melt signals a canary message.

But, the real shocker for many this past year has been the warmer winter and hotter summer in the Rockies and the iconic melt of Athabasca Glacier. Tourists have packed the lower level of Athabasca Glacier for many years and the markers at the base have noted, for the interested and curious, the century long shrinkage, of the glacier but none would have expected the furnace of a summer and the impact on Athabasca. Most of the more thoughtful have been, prophetic like, warning one and all about global warming and the various indicators of it: intense fires on the increase, drought conditions, longer stretches of hot days-nights sans rain and, to the point of this missive, the impact on glaciers. Glaciologists having been ringing the bell on this reality for many a year, writing on the wall obvious for those who know how to read the text. The publication a few years ago of Stan Peterson’s Ice Man: The Making of a Glaciologist (2013) is but one portal into such leadership, “First Years in Canada” (11) but a pointer to more substantive books such as Sanford’s 2017 beauty Our Vanishing Glaciers: The Snows of Yesteryear and the Future Climate of the Mountain West.

If we turn to the West Coast, Karl Ricker has been an engaged and thoughtful researcher on glacier retreat, 1965 initiating his work on Wedgemount glacier near Whistler, his work extending to Overlord glacier a few years afterwards. Karl was on a trip I led into the Assiniboine area more than a decade ago and his mountaineering and mountaineering years of research are at the highest level. Karl, now in his late 80s, has passed the baton to others who will continue their work on Wedgemount, Overlord, and other glaciers, faithful research revealing much that needs to be revealed.

The accelerated retreat of glaciers, Athabasca the most graphic in the winter-summer of 2023, is but multiple writings on the wall. Hopefully, the message will be read and acted upon before the consequences are irreversible.

*

Ron Dart has taught in the Department of Political Science, Philosophy, and Religious Studies at the University of the Fraser Valley since 1990. He was on staff with Amnesty International in the 1980s. He has published 40 books including Erasmus: Wild Bird (Create Space, 2017) and The North American High Tory Tradition (American Anglican Press, 2016). Editor’s note: Ron Dart has recently reviewed books by Jan Zwicky, Jan Zwicky & Robert V. Moody, D.L. (Donna) Stephen, Elizabeth May, Stephen Hui (Destination Hikes), Stephen Hui (105 Hikes) for The British Columbia Review. He has also contributed three essays: From Jalna to Timber Baron: Reflections on the life of H.R. MacMillan, Roderick Haig-Brown & Al Purdy, and Save Swiss Edelweiss Village to The BC Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1947 Canadian mountain culture and mountaineering”