1779 Canada’s Great War airmen

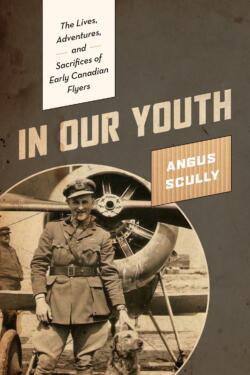

In Our Youth: The Lives, Adventures, and Sacrifices of Early Canadian Flyers

by Angus Scully

Victoria: Heritage House Publishing, 2022

$29.95 / 9781772034219

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

In In Our Youth, Angus Scully of the Vancouver Island Military Museum tasks himself with an ambitious mission: to evoke the history of Canadian aviation in the first decades of the twentieth century by dwelling first on this new form of aerial warfare and then on the postwar aviation industry that facilitated extraordinary leaps in continental and intercontinental travel. In Our Youth shows Canadians’ impressive role in the tragic and majestic aspects of aviation’s history in its early and trailblazing years.

In In Our Youth, Angus Scully of the Vancouver Island Military Museum tasks himself with an ambitious mission: to evoke the history of Canadian aviation in the first decades of the twentieth century by dwelling first on this new form of aerial warfare and then on the postwar aviation industry that facilitated extraordinary leaps in continental and intercontinental travel. In Our Youth shows Canadians’ impressive role in the tragic and majestic aspects of aviation’s history in its early and trailblazing years.

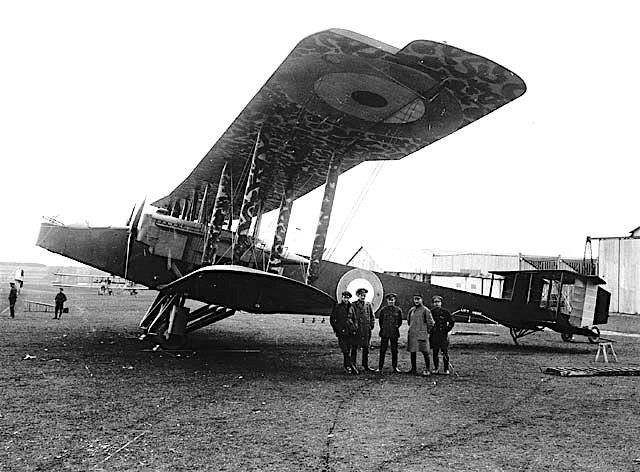

Scully’s success stems from his personal advantages. A Nanaimo archivist, he takes a hyper-focused approach to highlight three photographs of pioneering Canadian aviators: two group photos and an individual portrait. These images are not random novelties, picked out for their peculiar local charms. Scully justifies their place in his overall story by linking them to his impressive and precise research into a larger history of rapid technological innovation and global war. In Our Youth is not simply a book about the Great War and the development of aviation in Canada: it also provides a level of biographical interest made possible by Scully’s intense effort to justify his subjects’ important place in history.

In Our Youth’s first section serves to establish the beginnings of the aviation industry in Canada. This chapter’s central photograph is a group portrait of the class of 1916 students at Curtiss Flying School in Toronto. Scully provides an in-depth description of the history of that school, touching on the invention of, and early experimentation with, flying in North America; from the very beginning, Canada was integral to early aviation, its open geography serving as a prime location for pioneering groups like Sir Alexander Graham Bell’s team to experiment their machines on.

While detailing pioneering events in Canadian aviation, like the first flight in the British Empire (p. 18), Scully drives home that it was the First World War that established flight as a coherent industry. His focus on a group of flight cadets aptly displays this in a uniquely social way. With the onset of war, and the rise of the airplane as a particularly useful tool for it, aviation gained a new sort of image. What was first a world of eccentrically brave innovators became filled with romantic gentlemen-heroes: modern day knights. The famous flying aces — Billy Bishop in particular for Canadians — provide well-traversed territory in historical myth-making. Scully makes a notable effort to highlight the particular characters of those young men who sought to be aces, bringing to light in the process the particularly Canadian characteristics of his subjects.

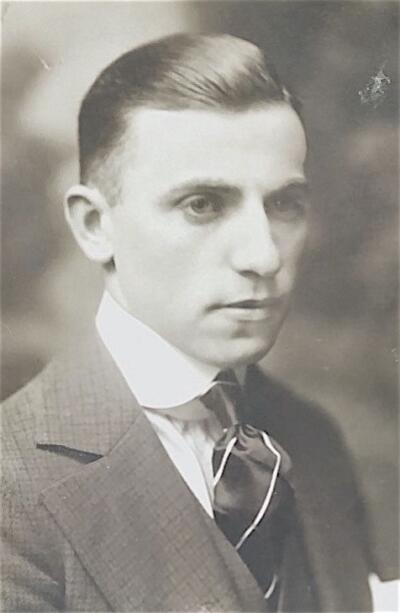

Scully’s second section delves deeper into the experience of early Canadian aviators in the First World War by focussing on Osborne J. Orr of Nanaimo, whom he regards as a fitting example of a young pilot walking the fine line between scoundrel and gentlemen. Born into a well-to-do British Columbian family, Orr was arrested as a youth for purse-snatching in Minnesota (p. 119) before later marrying an American woman who was not accepted by his Canadian parents. Orr’s inclusion in this book is testament to Scully’s intensive research. For years Orr, who would die flying in the war, remained a forgotten figure, with mistaken information — such as a document identifying him as American (p. 161) — that prevented even his simple inclusion in local war commemoration (p. 156).

Scully intimately relates his research process, his motivations, and his personal efforts to unearth historical information on Orr, and along the way he creates an intriguing tale. This story shows best the benefits of this type of localised history — the kind that involves emailing the subject’s remaining family as much as digging through archival documents (p. 163). Such research can have substantial remedial benefits, as described by Scully, for example Orr’s inclusion amongst the names etched into Nanaimo’s cenotaph and his recognition at his former school’s annual Remembrance Day ceremonies, two tributes that for decades he had been denied.

In the last section of In Our Youth, following two chapters that are respectively national and intimately personal in scope, Scully takes on a more province-focused approach with the stories of Captain Earl Godfrey and Lieutenant George Trim. By following them into the era after the Great War, Scully details the rise of civil aviation in BC and Canada. While Orr was also from BC, Trim and Godfrey’s stories feature the province much more integrally due to their surviving the war followed by their formative role in developing its aerial industry.

The stories of Trim and Godfrey reveal ambitious and danger-seeking war veterans adjusting to civilian life after serving as airmen in the largest conflict in history. They capitalised on the novelty, danger, and romance of flight through staged aerial shows throughout BC, and then explored the practical commercial opportunities in these early post-war years of aviation. Indeed, the excitement and celebrity of 1920s aviation was met with the fatality so often faced by both professional and amateur flyers alike. Scully paints BC in the 1920s as the perfect staging ground for the chaotic but fertile world of early aviation capitalism — the crossroads of innovative technology and wilderness.

Ultimately, In Our Youth provides fascinating insight into the role of BC and Canada in the ground-breaking developments of early aviation during the tumultuous First World War and the interwar years. For those who value personal histories that vary in approach and outlook without delving too far into the deep topical literature of aerial history, Scully’s book will not disappoint. Through its combined themes of youth in national identity, industry, and postwar aviation, this book will engage the reader with its vigour, focus, and confidence.

*

Matthew Vernon Downey graduated in 2021 with an honours BA in History and Political Science from the University of Victoria, and in 2022 gained an MSc in international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science. After a year in Southwark, England, he is back in Victoria. Editor’s note: Matthew Downey has also recently reviewed books by David Giblin, Bill Arnott, Catherine Marie Gilbert, David R. Gray, Grant Evans, and Terry Reksten for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1779 Canada’s Great War airmen”