1772 Daguerreotype to Kodak

Rare Merit: Women in Photography in Canada, 1840-1940

by Colleen Skidmore

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2022

$39.95 / 9780774867054

Reviewed by Maria Tippett

*

Anyone who ever doubted the presence of female photographers in Canada from the middle of the nineteenth century ought to read Rare Merit: Women in Photography in Canada, 1840-1940. Colleen Skidmore begins in 1841, when Mrs. Fletcher of Pictou, Nova Scotia produced an image ‘as perfect as the imagination can conceive,’ using the daguerreotype process (p. 1). Others followed during the ensuing decade, like the eight women whom Mrs. Fletcher herself trained. With the invention of a camera that, unlike the daguerreotype, could make more than one print, more women set up commercial photography studios, including Quebec City’s Élise L’Heureux Livernois and Victoria’s Hannah Maynard.

Anyone who ever doubted the presence of female photographers in Canada from the middle of the nineteenth century ought to read Rare Merit: Women in Photography in Canada, 1840-1940. Colleen Skidmore begins in 1841, when Mrs. Fletcher of Pictou, Nova Scotia produced an image ‘as perfect as the imagination can conceive,’ using the daguerreotype process (p. 1). Others followed during the ensuing decade, like the eight women whom Mrs. Fletcher herself trained. With the invention of a camera that, unlike the daguerreotype, could make more than one print, more women set up commercial photography studios, including Quebec City’s Élise L’Heureux Livernois and Victoria’s Hannah Maynard.

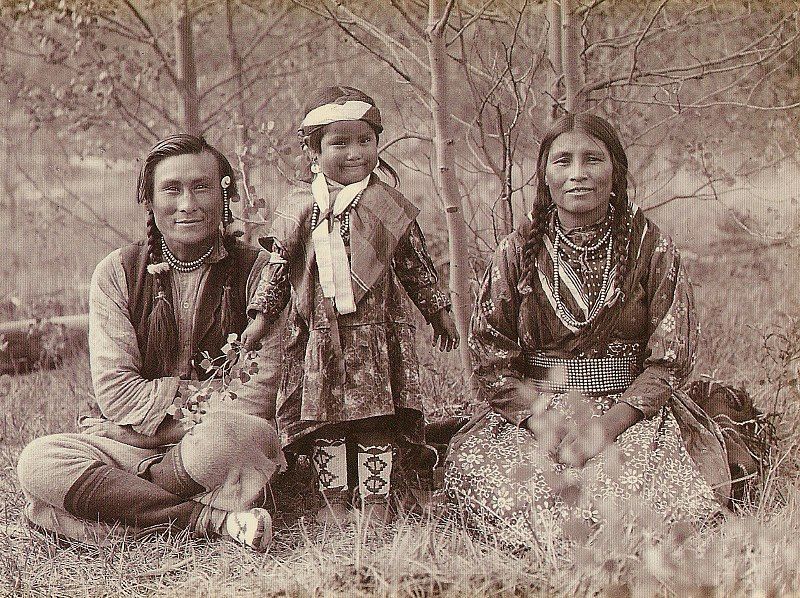

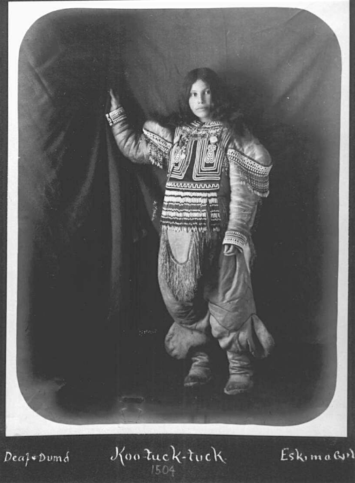

Not all women photographers set up their cameras indoors. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Toronto-born Geraldine Moodie travelled to the Eastern Arctic and to the Canadian prairies where she photographed the Inuit, Métis and Indigenous people. During the first decade of the twentieth century, the American photographer, Mary Schäffer took her camera to the Canadian Prairies and the Rockies. One of the results was her iconic portrait of Sampson and Leah Beaver and their daughter. Taken on the Saskatchewan Plains in 1907, The Beaver Family ‘disrupts conventions of ethnographic portraiture’ by capturing ‘a moment of personal connection and mutual respect’ between the photographer and her Indigenous subjects (pp. 158-159).

The invention of the Kodak camera in 1888 — it was light-weight, had flexible rolls that could take up to one hundred images and was easy to use — meant that anyone could take a picture. After travelling with her husband Lord Aberdeen across Canada in the comfort of their own railcar, amateur photographer Ishbel Marjoribanks Gordon (Countess of Aberdeen) took snapshots of immigrants, settlers and popular tourist sites. When she returned to London she published Through Canada with a Kodak (1899). The text and accompanying photographs, as Skidmore comments, showed ‘the potential for emigrant women, especially, but also men of lesser means or lower classes to obtain a more promising future as settlers in Canada’ (p. 155).

Most women photographers were not so adventurous as Moodie and Schäffer, or (like Lady Aberdeen) so openly committed to using their photographs to promote Canadian immigration. German-born Minna Keene (1861-1943) belonged to a new generation of female photographers. Called pictorialist photographers, their images ‘were distinguished by mastery of manipulation of light, texture, tone and contrast, composition, exposure, and printing papers and process’ (p. 249). Many of these female photographers participated in exhibitions and joined photography clubs. Unlike Minna Keene, however, they rarely saw their work published in Canadian magazines and newspapers or between the pages of a book.

Most female photographers taught themselves how to take photographs — or were taught by other women. If they joined a major photography studio, like Notman’s of Montreal, they worked as receptionists, or behind the scenes in printing, re-touching or mounting works taken by the firm’s male photographers. Those women who were married had to balance their professional careers with the needs of their children. And if they did have the luck to travel, like Lady Aberdeen and Geraldine Moodie, their itinerary was largely determined by their husbands.

If female photographers had a rough time of it, so have their subsequent biographers. Attribution of women’s photographs to male photographers is one problem. The absence of studio records, along with the lacunae of surviving photographs, in another.

Throughout Rare Merit Colleen Skidmore gives credit to those scholars who have made women’s photography the subject of their study, and on whom some of her own work is based. Nonetheless it is Skidmore herself who must be congratulated for now giving so many female photographers a place in the cultural history of Canada.

*

Author of over fifteen books dealing with the cultural history of Canada, Maria Tippett spent the formative years of her academic career as a sessional lecturer at Simon Fraser University, UBC, and the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Following her year as Robarts professor of Canadian studies at York University (1986–7), she lectured in South America, Europe, and Asia and curated exhibitions. In 1991, she returned to academe, becoming a member of the Faculty of History at Cambridge University and a senior research fellow and tutor at Churchill College, also at Cambridge. Her recent books include Sculpture in Canada: A History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2017), reviewed by Catherine Nutting, and Art for Art’s Sake (Pegasus, 2022), reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy. Among many awards, in 1980 she won the Sir John A. Macdonald Prize for her path-breaking Emily Carr: A Biography (Oxford University Press, 1979), which also won the Governor General’s Award for non-fiction. Editor’s note: Maria Tippett has recently reviewed books by Karen McKinlay Kurnaedy, Michael Audain, Sarah Milroy, Laura Bradbury & Rebecca Wellman, Kaija Pepper, and Mary Fox for The British Columbia Review, and contributed a memoir, “HRH: A nodding acquaintance.”

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster