1713 Getting emotional

Feeling Feminism: Activism, Affect, and Canada’s Second Wave

by Lara Campbell, Michael Dawson, and Catherine Gidney (editors)

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2022

$34.95 / 9780774866507

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

Increasingly I feel myself becoming historical. The feeling comes with advancing age, enhanced by encountering the work of a younger generation of scholars such as Lara Campbell. This is not the first time her research has left me unsettled and reassured, on the one hand unsettled to be in one’s lifetime the target of a future gaze, and on the other reassured to be recognised and unforgotten. That I react emotionally, with feelings, to the work of Campbell and her associates may reinforce the theory underpinning the book.

Increasingly I feel myself becoming historical. The feeling comes with advancing age, enhanced by encountering the work of a younger generation of scholars such as Lara Campbell. This is not the first time her research has left me unsettled and reassured, on the one hand unsettled to be in one’s lifetime the target of a future gaze, and on the other reassured to be recognised and unforgotten. That I react emotionally, with feelings, to the work of Campbell and her associates may reinforce the theory underpinning the book.

Affect theory includes serious study of the history of emotions, in this case, how emotions interacted with, and informed, the development of second-wave feminist activism. My first reaction protested that of course emotions were involved, of course my contemporaries felt strongly about the issues involved. How could it be otherwise? But it turns out to be not all that obvious. It also turns out to be an effective route into the stories to be told.

The other theory driving their thought is Intersectionality, of which there is a great deal in this book, and which, being interpreted, means that Life is complicated.

At the same time that Dr. Dick Grantley-Read encouraged us to insist on the full experience of natural childbirth, Betty Friedan invited us to take our potential beyond the role of homemaker. And we really, really wanted to have it all.

The twelve chapters, each by a different contributor, look at the “long second-wave” feminist movement, from the mid 1960s to the early 1990s, reaching back to the post-suffrage era of the 20s and 30s and extending into the present day; finding an interaction of power and emotions, differentiating between emotional women and rational women with emotions, and showing how women used genuine emotion as a tool to acquire control. Four of the contributors and one of the editors are male; it matters that there have always been some men who paid attention.

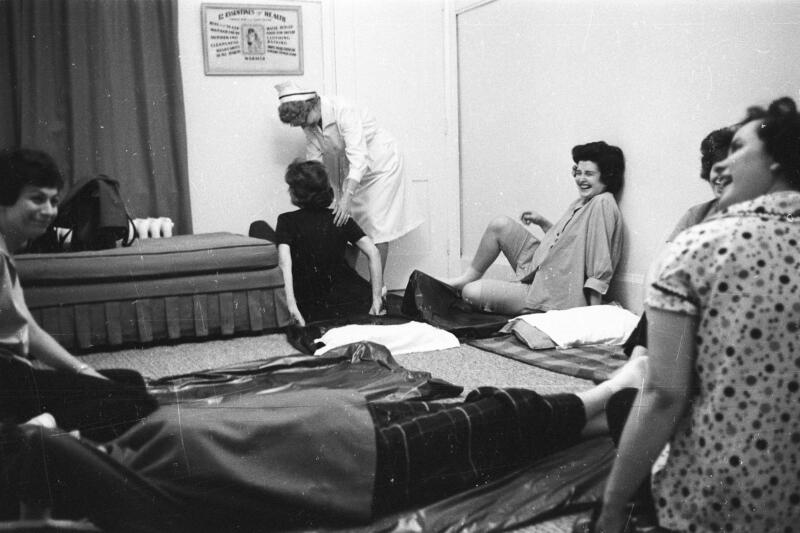

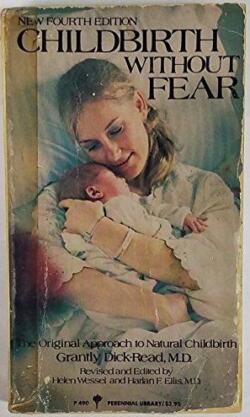

Each chapter is a case study of one aspect of the movement, different stories with some common threads. In Chapter 1, “Pride, Shame, and Anger; Women’s Struggles to Achieve Natural Childbirth in Postwar Canada,” Whitney Wood discovers women not rejecting their traditional maternal role, but on the contrary resisting what could be seen as a patriarchal authority blocking their right to fulfill that role. Dr. Grantley Dick-Read’s book Childbirth without Fear, first published in the United Kingdom in 1933, then in North America in 1944, convinced a generation of women that they had been missing something which should be reclaimed. The topic of “natural” childbirth as a possibility, a technique and even a right was much discussed by young women through the 1950s. I don’t recall believing that male doctors were deliberately over-ruling their female patients; it was more that they were being over-protective and too inclined to know what was best for us. Advances in surgery, medication and anaesthesia during the preceding 100 years had much improved the survival chances of mother and child; natural childbirth could be seen as a step backwards, subjecting us to unnecessary risk and pain. But a lot of women were willing to take the chance, and eventually doctors were willing to work with them. Use of forcible restraint and anaesthesia became less acceptable. We wanted to understand and participate in the process.

Wood quotes from letters written to Dr. Dick-Read by grateful women, who felt the need to express their gratitude directly and personally. She does not refrain from pointing out the paradox that these women tended to give all the credit to the father-figure, rather than to their own courage and tenacity in winning what was after all their own battle. She also points out that some influential female obstetricians were as firm as any father in proclaiming who knew best and finding it “grossly insulting that nineteen-year-old girls are advising mature, highly trained specialists how they want their babies delivered … the choice should be the doctor’s.”

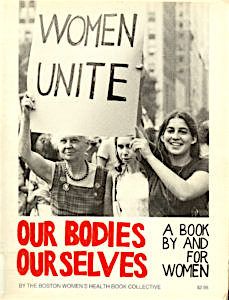

The natural childbirth epiphany foreshadowed “women’s individual and collective efforts to challenge medical authority and re-exert control over one’s own body.” Wood cites the influential 1973 volume Our Bodies, Ourselves and the growth of women’s health activism and the struggle for reproductive rights. The chapter is an interesting twist on current events; whether to have the baby, how to have the baby – and shouldn’t the choice be the women’s?

Wood introduces another thread: the feelings used and experienced in feminist activism may also be misused and abused. There are numerous reasons why a woman may not be able to give birth “naturally,” and why she may welcome medical expertise and assistance. Instead of pride and freedom, her feelings become disappointment, failure, and shame and self-blame, not helped when more “successful” mothers agree she should be blamed and shamed. Whether or not the shaming is intentional, it can hurt. I passed the natural childbirth test, but I was never able to breast-feed my babies; every once in a while, more than 50 years later, someone says something that leaves me feeling inferior and responsible for every negative thing that has ever happened to any of my children, things that would not have happened if I had tried harder, if I had not fed them formula.

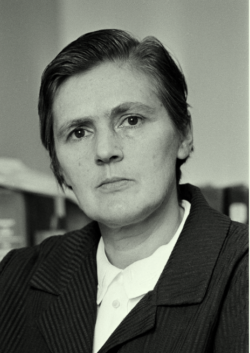

While abortion as such is not the central topic of any of the case studies, the issue hovers in the background of this and several other chapters. In Chapter 2,”The Good Mother of Science; Emotional Letters to Frances Oldham Kelsey during the Thalidomide Crisis” Cheryl Krasnick Warsh pits women’s right to manage their own reproductive health and to demand full disclosure about medications prescribed for their bodies, against the prerogatives of Big Pharma.

Thalidomide was developed in Europe during the 50s and became a popular sleeping remedy for both adults and children, as well as a remedy for severe morning sickness. It appeared innocuous enough to be sold without a prescription. By 1960 when the drug was recommended for the American market, there were hints of problems and in November 1961 it was withdrawn from the German market because of reports of abnormalities in children of users; the most horrific and vividly photographed were babies born without arms and legs, so hands and feet grew directly from their torsos. Meanwhile in Canada Thalidomide had been approved on the basis on information provided by the manufacturers.

Enter our heroine, Frances Oldham Kelsey, the “Good Mother of Science” (a title apparently bestowed by the author for this article). She was born in Cobble Hill, BC, a tiny community not far from my present location, and studied at McGill with a team chaired by James Bertram Collip, a colleague of Insulin pioneers Banting & Best. Warsh details the progress of Kelsey’s career as pharmacologist and physician as illustrative of the choices required of a married couple both of whom were professional. Kelsey became head of the New Drug Investigation Branch of the American Food and Drug Administration, where her meticulous research resulted in Congress banning Thalidomide early in 1962. The Canadian government took months longer to accept the evidence.

This is a complicated chapter, setting the Thalidomide story in the context of the Cold War and the widespread fear of nuclear fallout and resulting birth defects, the Vietnam War and public reactions to the visibility of disabled veterans and now of disabled children. The letters to Dr. Kelsey are strikingly united in sentiment, grateful for her saving the writers and their babies from a dreadful fate: there but for the grace of God and Dr. Kelsey, go I. Few of them seem concerned about the mothers who had taken the drug and suffered the consequences. It was not a question of dealing with disabled children; it was a matter of preventing them.

The women’s reactions were characterized as emotional and even frenzied, in contrast to the smooth, unemotional and stalwart behaviour of male doctors and even of husbands. And it is not over yet. As recently as 6 Dec 2022, the CBC carried a story about the drug domperidone: “Banned in the U.S., not approved for breastfeeding — why are so many moms taking this drug?”

Chapter 3 offers the Indigenous side of the story: “Therapeutic Political Spaces; Collective resistance among Indigenous women in British Columbia.” An associate professor of history at the University of Alberta, Sarah A. Nickel comes of Tk’emlupsemc (Kamloops Secwepemc), French Canadian and Ukrainian origins — being Canadian can be complicated. While most readers will be aware that one of the many faults of the Indian Act has been its differing treatment of women and men, many of us need to be enlightened on the extent to which Indigenous women determined to do something about this, as early as the 1930s to 50s. Early associations were initiated by the Department of Indian Affairs “to correct perceived deficiencies in Indigenous homemaking.” These were never enough, the perceptions were often misguided, and women leaders began to form their own organisations and networks, which included “provincial organizations focused on education, employment, health and legal issues.” Nickel traces the various clubs and societies, which were not all in agreement about women’s role. Women were used to a male-dominated world and they could not easily give themselves permission to break free. A major obstacle was the attitude of their own men:

Although male Indigenous leaders in British Columbia spoke frequently about the inappropriateness of emotion in politics, reminding their male peers not to “get emotional” in their decision-making, emotions in this context referred to female-coded reactions such as love, pain, and grief, not to male-coded feelings such as anger. In this case, men’s emotive responses were seen as acceptable and even useful, while women’s were perceived as threatening to the rationality, order, and patriarchy on which the Indigenous rights movement was based.

Their battle for legal status was entangled in conflicting laws and statutes: in 1974 “after a series of hopeful decisions acknowledging that Indigenous women who married Non-Indigenous men were treated differently from Indigenous men who married non-Indigenous women, the Supreme Court of Canada ultimately ruled that the Bill of Rights could not override Indian Act legislation.” But Nickel adds, “Despite this devastating defeat, the lengthy court process had broadly united Indigenous and non-Indigenous women in common cause.” She does not bring the discussion into the present day. She concludes “Indigenous women’s organizations were ubiquitous, albeit still marginalised, political forces, pursuing Indigenous women’s rights in a wide range of forms. In their multiple and sometimes overlapping capacities as feminists, mothers, and citizens, women used the therapeutic spaces of their organizations to recognised shared experiences and develop collective action.”

It would be interesting to know what Nickel makes of more recent modes of activism, especially by “allies” rather than by Indigenous women themselves, in which support for rights often seems to be all about emotion. Discussion towards reconciliation becomes impossible for fear of hurting someone’s “feelings.” Deep misunderstandings need to be addressed, but perhaps that is a later story and a different “wave.”

Kevin Brushett in Chapter 4: “Feeling my Way”; Women’s community activism in the Company of Young Canadians” reveals that even in such a squeaky clean organization as the CYC the role of women was invisible: “Like other New Left formations of the period, the CYC placed a premium on highly gendered forms of intellectualism.” His presentation of the “Long Sixties (1958-73)” as “fundamentally an emotional construct” is valid, but shocking and disillusioning, especially if you happened to have been there.

Life’s complications continue to build in Chapter 5, as Patrizia Gentile examines the bizarre world of “Tears and Tiaras: Affect, beauty pageants and protests.” We find “wholesome girl next door sex appeal wrapped up in white Canadian nationalism.” Protests emerge from within the system, decrying both commodification of women’s bodies and co-option of femininity by the state. The youth counterculture confronts the sociality of happiness. Feminist Killjoys “deployed anger & evoked anger.”

Women were not universally opposed to beauty pageants. And they still aren’t. On 16 Nov 2022 Emma Morrison became the first Indigenous woman to become Miss World Canada.

Chapter 6 examines another not always recognised aspect of activism, its absolute conviction of its own infallibility. In “‘Jesus is not part of this Collective’; secular passions and religious alienation among the Sisterhood,” Lynne Marks, Margaret Little, Marin Beck, Emma Paszat and Taylor Antoniazzi examine the moral certainty of individual feminism and its parallel in religious dogmatism. Some new feminists felt something akin to the conversion experience among evangelical Christians, some transferred from one emotional community to another. There was a creed to follow and shame if one failed to follow it. Of course not all feminists believed feminism and religion to be incompatible. In my own experience there was spillage in both directions, compassion within feminism, equality within Christianity. The authors cite the case of Vernon, BC, where the Anglican Church (which I knew well) donated the building for the transition house, although most transition house staff opposed religion as patriarchal.

Many immigrant women who took their religion as a basic part of life were made to feel even more alienated than they already did.

Similar problems as to who belongs and who doesn’t surface in Liz Millward’s Chapter 7: “Intense Times; Love, Fear, and Pride as Guides to Lesbian Feminist Organizing.” On the one hand, the era’s new sexual mores allowed for the excitement of sharing experiences, “a heady sense of erotic and political possibility.” On the other hand the search for a definition of “lesbian community” came close to the political dogmatism detected in the previous chapter. Community, Millward notes,

was organized around a theoretical approach and a sense of emotional and intellectual superiority to both gay men and gay women (as opposed to lesbians) who … were likely perceived as working-class and uneducated in feminist praxis. This sense of difference and superiority dictated … both how a woman would interpret her emotions and which emotions she should actually have — or at least be willing to admit that she had.

This does not sound pleasant and one begins to sympathise with “the bar dykes” who “don’t give two rips about feminism.”

But Millward writes sympathetically about the fear and anger, as well as the love, that urged lesbians towards a community of warmth and closeness, shared ideals, and exclusivity. She concludes: “Feminism gave many of these women the political language through which they could frame their tumultuous emotions.”

Most readers will have feelings about the topics of the next two chapters: pornography and prostitution. We are pretty sure neither is Good, but we are not sure what if anything should be done about them, and we can become uneasy thinking about them. A note at the beginning of Chapter 8, “Resisting Red Hot Video; Feminism, pornography, and the political utility of emotion,” the editors, like many of today’s news anchors, feel it necessary to apologise for possibly disturbing content. Are we unable to glimpse reality without our feelings getting the better of us? Who decides that some reality may be too much for us? Who is afraid of what might happen if our feelings are aroused? Who is protecting whom?

Those are my questions, not those of Eryk Martin, whose case study focuses on feminist activist opposition, resistance, and direct action, even firebombing, against the pornographic video chain Red Hot Video, in 1982 an addition to the sexual entertainment industry in British Columbia. His analysis of the historical context catches the intersection and clash of gender, sexuality, and various shades of “liberation.” The Pill (oral contraception) and VHS (Video Home System technology) were coterminous. Suddenly sexually explicit films were widely available for home consumption. Not all women’s groups rushed to set fire to buildings; more of them informed themselves about what was really happening, about how these films differed from earlier, age-old forms of pornography, and how they were affecting their viewers

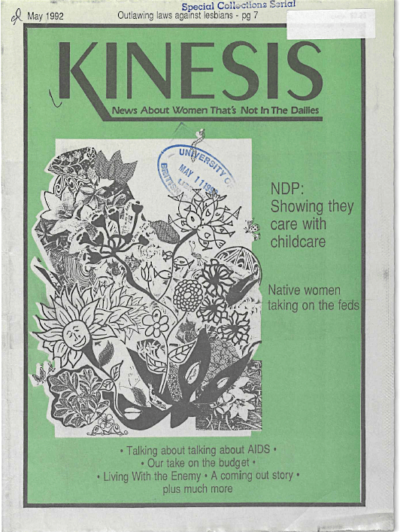

Martin and the author of the next chapter both cite the work of activist Regina Lorek, who “spent six months of 1983 watching and analysing pornographic films for the BC Federation of Women.” She constructed “an assessment that sought to recognise the complexity of emotion in pornography while at the same time creating a clear analysis that would be politically useful for feminist organizers.” Her talk to a public forum and printed in Kinesis, the magazine of the Vancouver Status of Women, is quoted at some length in the two chapters. She is frank about the effect of the videos on her own emotions and relationships, anger that her rage at what she witnessed spilled over into personal confrontation with her partner — not only what she was feeling, but a question as to what he was feeling. Her articulate account reveals a poisoning of natural human feelings and a sowing of distrust. Unlike much previous “erotica,” the films lacked any sense of tenderness, humour or consensus.

Many years later, Regina and I live in the same small island community and are able to talk about those times. An organization to which I belonged introduced a motion to lobby for stricter laws regulating pornography. As a librarian and student of modernist literature, I was wary of slipping back to the ages of censorship and book-banning from which we had only recently emerged. I spoke against the motion.

Prostitution is less the topic than the occasion for Chapter 9: “An Assumption of Shared Fear; Feminism, Sex Work, and the Sex Wars in 1980s Kinesis. ” “Assumption” is the operative word as Emma McKenna analyses the opinions expressed in the pages of Kinesis and finds an overwhelming assumption of the writers’ feelings of superiority, with little or no attempt to listen to the voices of sex-workers or porn actresses, whose silence was assumed. Here were educated, literate, middle-class women ready to speak for them, to preach about morality, without reference to economics or material reality. So the very people the activists claimed to champion were “shamed and humiliated by feminist appropriations,” excluded and marginalised from their own cause. McKenna finds an opposing movement among sex-workers themselves which “asserted that sexual labour in exchange for money was legitimate work, challenged the dehumanization of sex workers, and demanded the decriminalization of sexual labour.”

I became aware of this alter-movement though Jody Paterson’s advocacy in the pages of the Victoria Times-Colonist, and I regret that her work is nowhere acknowledged in this volume.

Meanwhile McKenna finds that “In privileging their own experiences of fear and anger over the lived experiences of sex workers, feminists asserted their emotional, philosophical, and civil authority over pornography and prostitution.” She concludes with a stern summary of the “feminist sex wars”:

the hegemonic feminist goal to abolish both prostitution and pornography neglected sex worker-led strategies of economic and resource redistribution that might have improved the material conditions of sex workers’ experiences and bodily safety. The refusal to privilege the desire for economic justice and bodily integrity of women working in the sex industry over feminist ideals of womenhood has had fatal effects that reverberate into the present.

Who has a right to feel at home within feminism?

While we examine our souls as we let all that sink it, Funké Aladejebi confront us with Chapter 10, “Emotional Scripts of Difference; Black Women teachers and Feminist Mobilization” and shows us feminism and racism have all too often gone hand-in-hand, complicated by issues of sexism and capitalism: “Black women’s feelings of anger and frustration shaped their advocacy work and led to the creation of organizations geared towards their intersectional experiences: “CANEWA [Canadian Negro Women’s Association] identified two key political concerns — the fact that male-dominated organizations like the National Black Coalition did not adequately address Black women’s concerns — and the tendency of white feminist groups to largely ignore issues of racism.” Again, it seems that white female anger is not universally helpful.

Chapter 11, besides adding a Quebec voice to the discussion, takes on the supposed bastion of free speech — the press. In “Briser le mur du silence”: Emotions, Gender and the 1981 Women Journalists’ Conference in Quebec,” Josette Brun, Laurie Laplanche and Sophie Doucet use the proceedings of one conference to target the feelings of marginalisation among female journalists. We have only to consider the recent experience of Lisa Laflamme with CTV to realise that this issue also is far from only a matter of history.

In the final chapter, “Anger, Melancholia, and Hope; the Feminist Politics of Emotion and the Centre for Women and Trans People at Wilfrid Laurier University,” Matthew Fesnak examines specific instances of feminist activism at one university in response to objectionable actions and attitudes by male students. I remember being glad that that I was out of the undergraduate world before the fad of “panty raids,” and dismissing with disgust the immaturity and insensitivity of male students who thought such exploits were a natural part of their god-given puberty ritual. Fesnak sets his argument within a campus framework during the 1980s and 90s, the evolution of women’s studies and the gradual emergence of a movement which pushed definitions of gender and sexual identity. He uses the complex concept of “melancholia” to discuss emotions and sense of loss around the recognition of one’s self and hoped-for ideals. He concludes:

The activities of the Centre for Women and Trans People have affected (and benefitted) many people over its years of existence, not because undergraduates are easily influenced, but because the ideas and politics of the space resonate with so many, and because it has grown and changed in accordance with criticisms of the second wave. The name “Women’s Centre” was important when the organization began, in order to combat the sexism and misogyny reflected in the panty raids, and the name “Centre for Women and Trans People” continues to be important in the 2020s because of the harassment and hatred transgender students face on campus.

And that’s it. The books ends there — with the final sentence of Chapter 12 and the plight of transgender students on campus, leaving us with more melancholia than hope. No editorial epilogue exists to relate the twelve essays and tie together some continuing and enlightening threads with relevance for whatever Wave this is.

To call this book thought-provoking is a profound understatement. It also evokes a more emotional response than one expects from a scholarly history (or herstory). A reader might be driven to self-examination and some thought about how empathy can become exceptionalism.

I need to sign off by citing a new video posted on YouTube by feminist artist Sheila Norgate: Even Barbie is Pissed with its introductory statement, :”According to the BBC, after analyzing ten years’ worth of World Gallop Polls, it has come to their attention, that women are getting angrier. Geeze … I wonder what THAT could be about.”

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve writes about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. She co-founded the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina on Gabriola Island. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has recently reviewed books by Donald Lawrence, Josephine Mills, & Emily Dundas Oke, Iain Lawrence, Lisa Anne Smith, Mowafa Said Househ, Eric Schmaltz & Christopher Doody, and Carolyn Daley.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “1713 Getting emotional”

Thanks, Ann. And yes, we’re still pushy.

This is a brilliant review in that I want to read the book NOW. It also resonates with my experiences coming of age in the 1960s. I remember being asked if I was at U of T to get my MRS degree. You were a failure if not engaged by grad. (I was). And then the subsequent years of turmoil and progress and being pushy, unfeminine, and the list goes on. Life was indeed complicated and still is. Congratulations Phyllis Reeve for such an astute review and to the SFU editors for compiling a controversial and compelling anthology. We aren’t done yet.