1587 Monsieur Maillardville

Johnny of Maillardville

by Marie-Laure Chevrier with illustrations by Michael Kluckner

Vancouver: Midtown Press, 2021

$15.95/ 9781988242422

*

Monsieur Maillardville: Un Pionnier Visionnaire

par Marie-Laure Chevrier avec illustrations par Michael Kluckner

Vancouver: Éditions du Pacifique Nord-Ouest, 2021

$15.95 / 9782925064121

Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

*

Michael Kluckner’s colourful cover, his black and white sketches that adorn many pages, and the enormous font of the text in this slim volume give it the appearance of a book designed for beginning readers. The book was written for educational purposes but for older students and adults seeking an introduction to what was a major French-Canadian settlement in British Columbia. For twenty-three years, the author, Marie-Laure Chevrier, a native of Quebec, taught in a francophone school in Coquitlam, the municipality which includes the community of Maillardville. A need for local history material inspired her to write Monsieur Maillardville: Un Pionnier Visionnaire which, translated by Louis Anctil, has been published as Johnny of Maillardville.

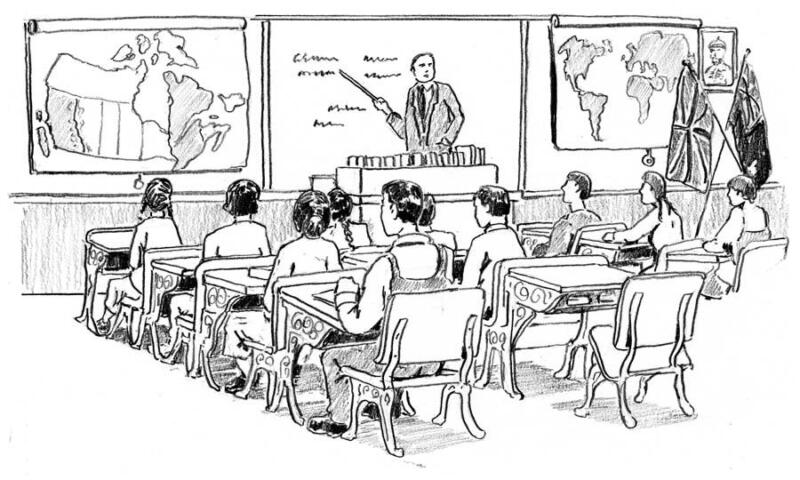

“Johnny” was a real person, Jean Baptiste Dicaire, Jr., a native of Hull, Quebec. In September 1909, aged 17, he came to Maillardville with his parents and two younger brothers. His father’s work as a lumber grader meant that the family followed his work. Thus, Johnny spent some time in Ontario public schools where he learned to speak English fluently. That was a great advantage in British Columbia and is part of the book’s moral.

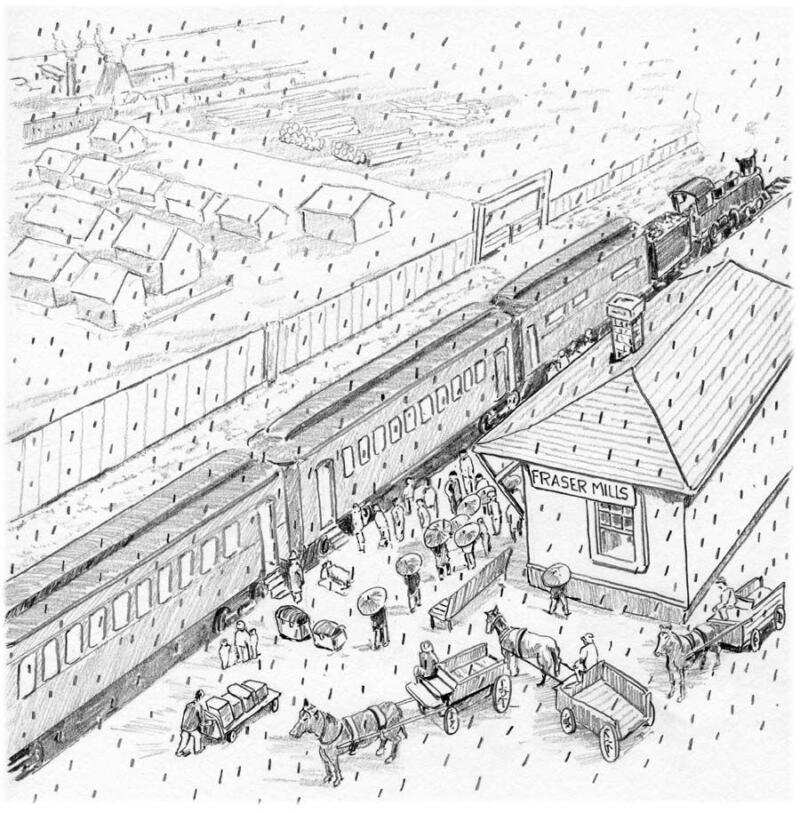

The Dicaires were part of a cadre of about forty French-Canadian families from around Ottawa and Sherbrooke who were recruited by Father Patrick O’Boyle, OMI on behalf of the Canadian Western Lumber Company, whose Fraser Mills once boasted of being the largest lumber mill in the British Empire. Another priest, Father Edmond Maillard, OMI, however, greeted the new arrivals, and the settlement was named after him. After a brief sojourn in company housing at the mill site, a company town, the Dicaire family, like most of the French Canadians moved up the hill to Maillardville.

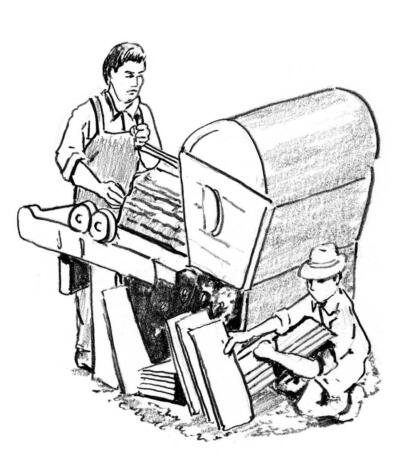

Johnny, like his father, worked at the mill and in time became a shingle sawyer, a highly skilled position. He served the community as a volunteer fireman, married a woman he met on the train heading west, and began raising a family. The Depression of the 1930s was hard. Because the company reduced wages several times, the family had to remove their children from the Catholic school which, without government support, depended on tuition fees. At the public school the children quickly learned English. Although only tangentially part of Johnny’s story, the book includes a brief account of the 1951 strike when the community closed its two Catholic schools and sent their 840 students to the already overcrowded local public schools as part of a campaign for government support of Catholic schools.

Of great impact on the family economy was Johnny’s decision to be one of the first men to join the union being formed at the mill. Chevrier does not mention that the Communist-led Lumber Workers Industrial Union organized it. Even before the 1931 strike, Johnny’s union membership cost him his job and access to the sacraments at the parish church. After a period of unemployment, Johnny found work in a Vancouver shingle mill owned by “a Mr. McKercher” who is not otherwise identified. It was likely Joseph A. McKercher, who despite his Scottish name, was a French-Canadian from Quebec.

Eventually, Canadian Western Lumber re-hired Johnny and the church welcomed him back. He developed a sideline as a square-dance caller and opened a pool hall. He became more involved in voluntary projects of which the most important was promoting the construction of the seniors’ residence and social centre that became Foyer Maillardville. Such activities helped to earn him the title, “Monsieur Maillardville.”

For the most part, Chevrier’s account rings true. A typo, however, caused wonderment. Dating the opening of Our Lady of Lourdes church as 1920 raises a question of why it took so long to establish a church. The correct date, 1910, is in the French edition. In dealing with local politics, Chevrier notes that George Proulx, the proprietor of a general store and postmaster, was elected “mayor” of Coquitlam in 1923. [The title was reeve.] He served only one year. Tantalizingly, “bad luck” is the only explanation. If Mme. Chevrier should write another book on Maillardville, Proulx would be an excellent subject.

Johnny was proud of his ability to speak both French and English fluently, a talent which contributed to his role as a community leader. Recognizing the value of bilingualism, he learned a few phrases so he could greet fellow workers in their native language, be it Chinese, Japanese, or Punjabi. And, to recognize French in the much larger Anglo community, at public gatherings he often sang along with “O Canada,” but in French. Towards the end of his long life, Johnny told an interviewer: “A second language is the best thing a person can master” (p. 99). That good lesson is the moral of this brief and very readable biography.

*

Patricia E. Roy, professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria, grew up in New Westminster. She remembers family Sunday drives through Maillardville en route to visiting Mr. McKercher, her father’s elderly friend, who retired to Haney. Patricia Roy is the author of Vancouver: An Illustrated History (Lorimer, 1980) and The Illustrated History of Canada: British Columbia. Land of Promises (Oxford University Press, 2005), with John Herd Thompson, and is known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989), The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007), all published by UBC Press. Her most recent books are Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012) and The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Royal BC Museum, 2018), reviewed here by Chad Reimer. Editor’s note: Patricia Roy has recently reviewed books by Daniel Francis, Grace Eiko Thomson, George M. Abbott, Jesse Donaldson, Linda Kawamoto Reid, John Endo Greenaway, & Fumiko Greenaway, and Kotaro Hayashi, Fumio Kanno, Henry Tanaka, & Jim Tanaka for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster