1588 Wit, irony, and blackberries

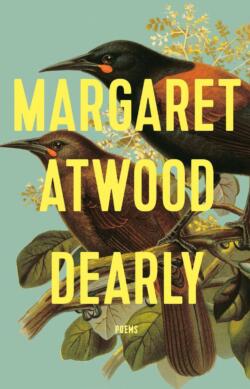

Dearly

by Margaret Atwood

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (McClelland & Stewart), 2020

$24.00 / 9780771000799

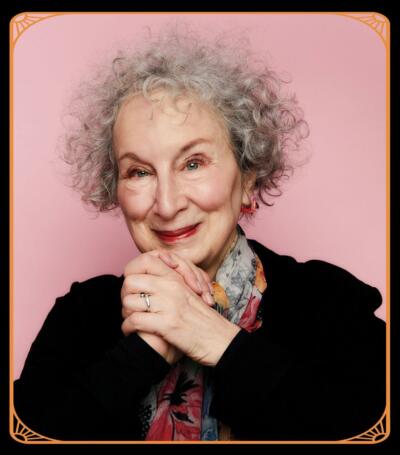

Reviewed by gillian harding-russell

*

In Dearly, Margaret Atwood returns with a poetry collection after nearly two decades since Morning in the Burned House (1995). The poems do not disappoint. Here the unexpected angles of perception with their edge of irony take on the greater weight of wisdom with age tempered by humour and kindness. Although the poet’s critical eye is still cast on social mores, here expanded from a traditional view of the feminist as victim to a more sexually-inclusive view of women sharing that predatory impulse, there is a deepening humanity and humility as the poet writes from an octogenarian year and after the double loss of a loved one, first to dementia and then to death itself.

In Dearly, Margaret Atwood returns with a poetry collection after nearly two decades since Morning in the Burned House (1995). The poems do not disappoint. Here the unexpected angles of perception with their edge of irony take on the greater weight of wisdom with age tempered by humour and kindness. Although the poet’s critical eye is still cast on social mores, here expanded from a traditional view of the feminist as victim to a more sexually-inclusive view of women sharing that predatory impulse, there is a deepening humanity and humility as the poet writes from an octogenarian year and after the double loss of a loved one, first to dementia and then to death itself.

As a kind of prologue for the collection, Atwood in the first poem “Late Poems” warns the reader that the poems that follow are “like a letter sent by a sailor/ that arrives after he has drowned,” or as a romantically conceived and futile message sent in a bottle, “late” as in “[w]hatever it was has happened,” whether the “battle” or “the sunny day” or “the moonlit/ slipping into lust.” In an implied reference to a minstrel at an inn with barrels of beer on tap, Atwood swerves from melancholy to a drunken mock-maudlin as she urges the reader to celebrate the rest of the evening’s celebration and, by extension, the rest of the poems in the collection:

It’s late, it’s very late;

too late for dancing.

Still, sing what you can.

Turn up the light: sing on,

sing: On.

That the cup, if not half full, at least has something worth tasting at its dregs becomes the suggestion. Old age apparently too has its rewards.

In “Ghost Cat,” Atwood examines dementia from the perspective of an aging cat in its final stages of forgetfulness and despair. From the conversational opening, “Cats suffer from dementia too. Did you know that?” Atwood moves to pathos with the cat shut out from the familiar bedroom to aimlessly wander in search for an environment that it no longer recognizes but that once offered comfort:

Clawing at the bedroom door

shut tight against her. Let me in,

enclose me, tell me who I was.

No good. No purring. No contentment. Out

into the darkest cave of the dining room,

then in, then out, forlorn.

Identifying with the cat’s plight – whose dementia echoes her ornithologist and writer husband Graeme Gibson’s tragic memory loss – Atwood cuts to the quick to suggest a universality of encroaching mental and bodily afflictions that affect us all so that there are no victors in old age. The speaker pleads that when she too “grow[s] fur, start[s] howling” and “scratches at your airwaves” others cannot hear, that you, the reader, too will turn the “key. Bar the window” on her from the now unfamiliar bedroom as well.

With the metaphorical evening’s entertainment suggested by the introductory “Late Poems” ahead, Atwood approaches today’s mores and views on sexuality from unforeseen angles that draw on the past and a future yet to materialize. In “Digging up the Scythians,” a tableau of an excavation of warrior maidens presents us with “dagger girls,” first feminists who defended themselves to the death, since “What did you expect?” the speaker addresses the reader equably, “they knew what happened if you lost:/ rape, death, death, rape.” But with a comical twist that overturns suggestion of self-righteous feminist rage, Atwood adds that these warrior women also fought as others (i.e., men) would more practically “for the loot, if victorious.”

A futuristic take on sex that turns the tables on the stereotype of men-aggressors comes in startling Atwood-style in “Double-Entry Slug Sex.” With playful irony, the speaker argues, “If we could reproduce by bud/ or spore, there would not be these duels.” If we all were equally sexed, and either “could swivel an identical/ organ into the other’s ear/ while both twirled in the air” wouldn’t sex be more equitable? While avoiding feminist preaching, Atwood turns to the alarming pronouncement, “No help for it but chewing off/ a penis.” Blackly comic in its hilarity comes the childish complaint, “My turn! You bit off mine last time.”

Get on with it or we will be here all night,

fair game for predators.

No longer does gender in this androgynous world matter, but instead the practicality of evading a predator becomes uppermost. Similarly, in “Update on Werewolves,” the werewolves are not all male, but include “long-legged women” in “furry warmups” or a “pack of kinky models/ in sado French Vogue getups” so that the tables are turned in this complicated society where the roles have changed but the human problems are not so different.

Like Morning in the Burned House, Dearly is elegiac and rooted in a carpe diem theme, but while the former reflects more distantly on a parent’s death, the latter focuses on what is arguably the more intensely experienced and life-changing event of a partner’s dementia and death, and the personal experience of aging more generally. In “Walking in a Madman’s Wood,” the tangled wood becomes a metaphor for the madman’s mind, with the red markers placed along a path to assist where brain passages no longer prove active. In the title poem “Dearly,” the poet weighs the meaning of the word “dearly,” as inherited from what seems an archaic past. Each mention of the word is spoken as if in religious recitation. “Dearly. How was it used?”:

Dearly beloved.

Dearly beloved, we are gathered.

Dearly beloved, we are gathered here

in this forgotten photo album

I came across recently.

Just as the yesterday’s ceremonies have been forgotten so too have the Polaroid photos that appear in the album as “the newborn” asks, “What is a Polaroid.” And, in an ironic turn, to add further perspective, the speaker adds “Newborn a decade ago.”

In Atwood’s vision, “every life” may be seen as something of a “failure” since even a “high flyer[’s]” life ends with a death. Still, the poet finds optimism in a projected battle scene of life and death when she salvages a “feather”– symbol of the spirit or soul – from a bird fallen to its prey to write that poem. “But nothing, we like to think,” the speaker adds,

is wasted, so I picked up one plume from the slaughter,

sharpened and split the quill,

hunted for ink

Using the feather to inspire memory and creation, the poet writes “The Feather,” and makes art out of a small tragedy like the minstrel in the opening poem.

In the wise and lovely cumulative poem “Blackberries,” the speaker, however, comes to terms with age and expresses gratitude for what has been her lot. After presenting blackberries in their beauty and promise for enjoyment, in which each berry is savoured by squirrels, bears and the speaker in their own way, Atwood closes in on the reader with this warning:

Once, this old woman

I’m conjuring up for you

would have been my grandmother.

Today it’s me.

Years from now it might be you,

if you’re quite lucky.

And so, none of us are immune from age and the diminution of our powers that may also been seen as a pinnacle of experience and enduring that one must be grateful for.

Atwood’s Dearly is a collection that is like that bowl of blackberries: each poem a blackberry nurtured in the sun with the best ones grown in the shade of contemplation and from the mature perspective of autumn and ripeness. While I may borrow Atwood’s novels from the library, I will preserve a space on my book shelf for this wise and, at moments, startlingly funny collection.

*

gillian harding-russell is a Regina poet and reviewer. She has five poetry collections published, the most recent In Another Air (Radiant Press, 2018) and Uninterrupted (Ekstasis Editions, 2020). Both were shortlisted for Saskatchewan Book Awards. In 2016, a poem sequence Making Sense won first prize in Exile’s Gwendolyn MacEwen Chapbook Award. She has a B.A. (Hons) and M.A. from McGill and her Ph.D. (in English Literature) from the University of Saskatchewan. Visit her website here. Editor’s note: gillian harding-russell has also reviewed books by Patrick Lane and Yvonne Blomer for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1588 Wit, irony, and blackberries”