1442 a carriage that were green

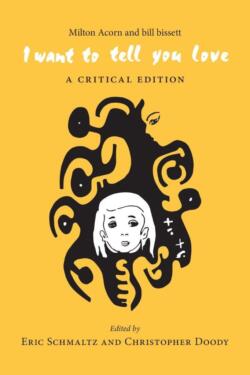

I Want to Tell You Love: A Critical Edition

by Milton Acorn and bill bissett, edited by Eric Schmaltz and Christopher Doody

Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2021

$29.99 / 9781773852294

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

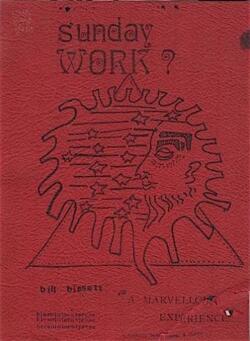

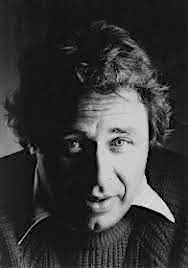

Early in the 1960s, that fabled age, two poets from the Maritimes encountered each other in Vancouver and planned an unlikely collaboration. I want to tell you Love comes to us as a long-lost gift, unearthed like buried treasure from the depths of Library and Archives Canada and Special Collections at York University. Milton Acorn (1923-1986) had a reputation rooted in the Imagists and the politics and poetics of modernism. bill bissett, born in 1939, was just beginning to invent himself and a whole new way of dealing with language and spelling, of rearranging the page and “misusing the typewriter.” From different generations, they might have been Ariel and Caliban ganging up on Prospero’s established world. bissett, whose lowercase name is only the most obvious of his orthographic manipulations, has been described by fellow poet Jamie Reid as “a strange, shy, fey, gaunt youth” [in Linda Rogers, ed. bill bissett: Essays on His Works (Toronto: Guernica, 2002)]. Acorn, on the other hand, bore more than a passing resemblance to the magisterial beast he would celebrate in his great poem “A Natural History of Elephants.”

Early in the 1960s, that fabled age, two poets from the Maritimes encountered each other in Vancouver and planned an unlikely collaboration. I want to tell you Love comes to us as a long-lost gift, unearthed like buried treasure from the depths of Library and Archives Canada and Special Collections at York University. Milton Acorn (1923-1986) had a reputation rooted in the Imagists and the politics and poetics of modernism. bill bissett, born in 1939, was just beginning to invent himself and a whole new way of dealing with language and spelling, of rearranging the page and “misusing the typewriter.” From different generations, they might have been Ariel and Caliban ganging up on Prospero’s established world. bissett, whose lowercase name is only the most obvious of his orthographic manipulations, has been described by fellow poet Jamie Reid as “a strange, shy, fey, gaunt youth” [in Linda Rogers, ed. bill bissett: Essays on His Works (Toronto: Guernica, 2002)]. Acorn, on the other hand, bore more than a passing resemblance to the magisterial beast he would celebrate in his great poem “A Natural History of Elephants.”

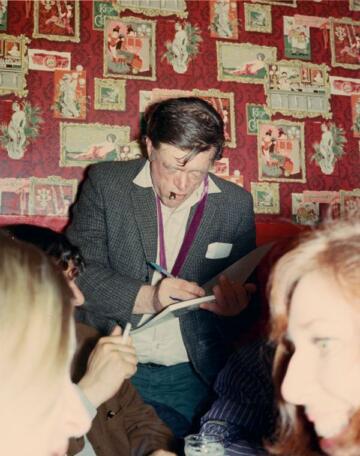

Each possessed a recognisable style and a belief in the power of words. Acorn’s radical politics and bissett’s radical formal experiments reflected their shared hope for a “revolutionary possibility.” Though very different personalities, both were outrageous, charismatic and frequently irresistible, especially when they performed poetry before “performance poetry” became a thing.

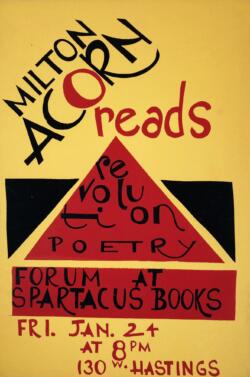

Vancouver was home to conflicting poetry scenes, one centred in academia around professor Warren Tallman at the University of British Columbia, where Frank Davey, George Bowering and Lionel Kearns turned up in graduate English classes and Americans such as Robert Duncan and Robert Creeley and the Black Mountain group visited, read and influenced. Another, including poets Judith Copithorne, Al Neil, Pat Lowther, Dorothy Livesay, Patrick Lane, Beth Jankola, Acorn and bissett, flourished downtown in clubs and cafes where the Beatnik ambience persisted, in the Socialist centre Vanguard Books on Granville Street, and a little later in the Advance Mattress Coffee House on west 10th, geographically closer to UBC. The downtown poets liked to rail against the academics, though it is not clear why the influence of the American Black Mountain Group was more pernicious than that of the American Beatniks, or Duncan more sinister than Ginsberg, but feelings could run high. The editors observe: “Vancouver’s seemingly divided literary communities were unified by sensitivity to the turbulent sociopolitcal conditions of the time.” In the event, many from both camps in due course became good grey poets who embraced academia by teaching in creative writing departments and serving as poets in residence.

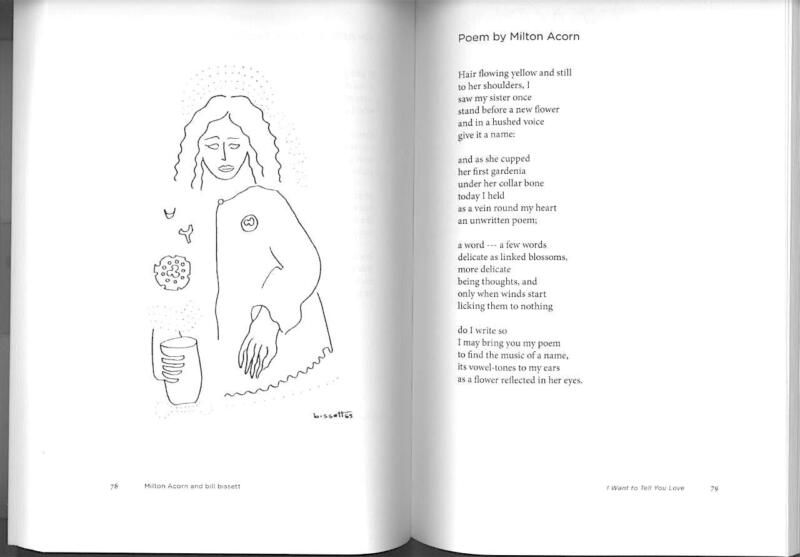

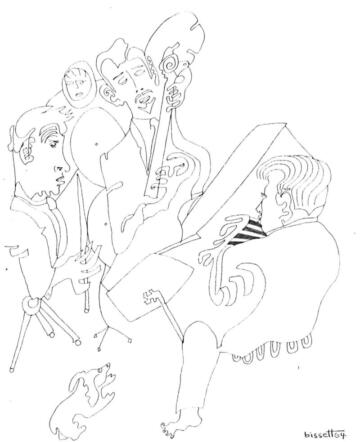

A lot of talking went on around the Vanguard events, and the actual reading was one sort of talking. Conversation was another. The book at the centre of the present volume was born in conversations. bissett remembered: “milton n me wud talk 4 hours n hours n walk n talk n talk n walk” and “thru our talking th idea uv our dewing a book 2gethr was n did evolv sew undrfulee” [Notice how bissett makes you stop and notice the sentence — that’s what he does]. The poems were not talking to each other, but co-existing beside each other, not composed in response or reaction to each other, but rather in simultaneous responses and reactions to the same places at the same times. It was “a book uv poetree by 2 poets diffrent n similar” in a milieu hoping to make love not war. What holds these styles and positions together for the authors is love. Hence the title I want to tell you love is the title not of any single poem but of the collection of thirty-nine poems by Acorn, twenty-two poems by bissett and ten drawings by bissett.

As bissett remarked to Eric Schmaltz in an extended email interview, included in this book: “diffrens is not opposisyan diffrens is enhansing” and that of course is the rationale for this project. But the publishers, even those usually sympathetic like Raymond Souster and Fred Cogswell, didn’t get it. After too many refusals, Acorn and bissett submitted most of the poems, one by one, for publication elsewhere. I want to tell you love sank out of sight and mind — until now, when returned to their intended collaborative context, the poems can “begin to perform anew.”

I am not going to “review” the poems. Much continues to be written about both poets and their work. This is a “critical edition,” and it is the critical setting for the central recovered jewel that requires scrutiny. Eric Schmaltz’s Critical Introduction is a history lesson for most readers and a reminder for the rest of us about a vital time in Canadian cultural life. The sections “The Vancouver Sixties Poetic Milieu” and “In Vancouver: Milton Acorn and bill bissett” in the “Critical Introduction” provide a useful and fascinating context for the collaboration. But the narrative is not free of errors. For instance, readers and scholars interested in the brothers Richard (Red) and Patrick Lane need to know that Red, who died in 1964, was the older “esteemed” poet and Patrick the younger “emerging” poet — not the reverse, as Schmaltz has it.

The section “A Textual History” looks at the fate of the text, and “Thinking in Mosaics” offers useful analysis of just what was going on in these poems, using words like “mosaic” and “assemblage,” speculating on the romantic basis of the avant-garde, and looking at how all this fits with scholarly critical theory then and subsequently.

“Afterlives” wonders what the book might have accomplished had it been published when planned: “I Want to Tell You Love would have been significant to Vancouver’s cultural and political climate by offering a clear bridge between its distinctive literary and activist communities and may have inspired additional forms of political and artistic action.” It could have served as a “generational transition moment.”

The original book was typewritten and stapled on letter-sized paper, and has been transformed here into a less eccentric format. The poems remain as planned for the collaboration, with later emendations for later publications listed separately. The cover image by bissett is the one originally intended. So this is not a facsimile, but something more accessible and less archaeological.

Acorn’s “Elaboration on a Text … for Joe Rosenblatt” earns a single brief note: “This poem is dedicated to Canadian poet Joe Rosenblatt, a friend of Acorn.” That is true, but breathtakingly inadequate. Rosenblatt has written extensively and with deep emotion about his complicated relationship with Acorn, especially in The Lunatic Muse; essays and reflections (Exile Editions, 2007). Rosenblatt was ten years younger, and Acorn a difficult mentor, but the refrain of this poem – “Speak for me Joe!/ As crude fingers/ search the guts/ of an oyster,/ search yourself” –was the mantra which played in his mind, Rosenblatt says, just as he was on the point of giving up. He did search himself and he did search the guts, and he did speak — even if not always for Acorn. This poem contains not only biographical details but a whole poetic theory and enough material for several doctoral dissertations.

Then there is bissett’s poem “a carriage that were green” which also merits only one note, and that identifying a street in Kitsilano where bissett lived. It’s another missed opportunity — this time to relate the poem to Schmaltz’s introductory discussion of the counter-culture’s cosmic idealism and expanded consciousness which “could lead to material change.” bissett’s incantatory readings often seemed like a sort of revelation, which could be experienced even by hopelessly uncool listeners such as myself, without benefit of controlled substances:

o, if ever

there were

a carriage

that were

green,

mushroom

and banners

flow

from behind

stops for

lunch on

orange

toadstools

blue sky

above, all

green

clear, below

sun turns

carriage

wheels

clouds

exhaust

of dragon snouts

over

pyramid

lake.

Am I the only one who catches a glimpse of Lucy in the Sky, and sniffs a puff of something magic?

I said I am not going to “review” the poems, so I won’t, but I wish Schmaltz and Doody would expand their commentary, dig deeper, disagree with my suggestions if required. I missed a sense of the electricity in a room when Acorn or bissett was reading. The events related occurred two decades before either editor was born. Doody earned his doctorate from Carleton in 2016, and Schmaltz his from York in 2018. I tell myself not to be so churlish as to mutter, “you had to be there.” I am grateful that a later generation realises the importance of the time they are documenting.

Postscript: The first time a family friend and emerging poet invited us to a reading at Vanguard Books, we inadvertently caused consternation among the assembled avant-garde. My husband, a brand new doctor interning at St. Paul’s Hospital a few blocks away, and conscious of his public image, wore jacket and tie. Settled inconspicuously (we thought) into back seats, we felt ourselves the target of hostile stares. Our friend realised they had mistaken us for under-cover cops, albeit somewhat obvious and inept, and hastened to vouch for us. A useful lesson in dress codes.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve writes about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. She co-founded the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina on Gabriola Island. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has recently reviewed books by Carolyn Daley, Roy Innes, Veronica Strong-Boag, Ian Hanomansing, PJ Patten, Marion McKinnon Crook, and Daphne Marlatt.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

11 comments on “1442 a carriage that were green”

Phyllis Reeve’s review took me back forty-odd years to the night my husband and I gave Milton Acorn a ride, following his reading in a tony Saskatoon neighbourhood!

Charlotte – when I am home at the end of April we must get together and compare our experiences of chauffering Milton.

An engaging review. Might have been valuable to draw Marya Fiamengo and Robin Mathews into the literary and political culture wars of such a period of time; Mathews and Fiamengo were also good friends of Acorn. I spent a lovely few days with Rosenblatt a few years ago with another fine BC poet, a Purdy-Layton friend, Doug Beardsley — a fuller tale yet to be told. The literary-culture wars of decades past are ever with us. Phyllis Reeve’s review is a beauty and bounty, revealing her and the editors’ evidence of much-needed sleuth work. — Ron Dart

Claudia Cornwall wrote something about Marya Fiamengo’s contribution in Mother Tongue Publishing’s volume on “The Life and Art of Frank Molnar, Jack Hardman and Leroy Jensen” but Marya slips from that story after she and Jack separated. Our paths crossed briefly in various contexts and we had several mutual friends, among them Mary Goldie, who told me firmly that Marya’s contributions poetic and otherwise were shockingly underappreciated. I know you have told parts of this story yourself. How about more?

lovely review. Looking forward to seeing the book!