1153 Home on leave from Penang

Then Now

by Daphne Marlatt

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2021

$16.95 / 9781772012873

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

The generation of Marlatt’s parents, and of my own, took the British Empire for granted. Government agencies were as feckless then as now (note the book’s title), but one got on with one’s job in business or the civil service or wherever duty led, and left to us, their children, letters and journals perfumed with naivety and courage and joie de vivre.

The generation of Marlatt’s parents, and of my own, took the British Empire for granted. Government agencies were as feckless then as now (note the book’s title), but one got on with one’s job in business or the civil service or wherever duty led, and left to us, their children, letters and journals perfumed with naivety and courage and joie de vivre.

What to do with those documents? Archivists can preserve them to be referenced by historians or polemicists. Prose writers can publish them as narratives. A poet, specifically Daphne Marlatt, can write poems to walk along side her father’s letters, responding to him intimately across the years.

This source has nourished her work before, notably in the poem-letter-journal sequence “Month of Hungry Ghosts” and her novel Taken. These and the present work were each prompted by a return to Penang and the evocation of long-buried memories.

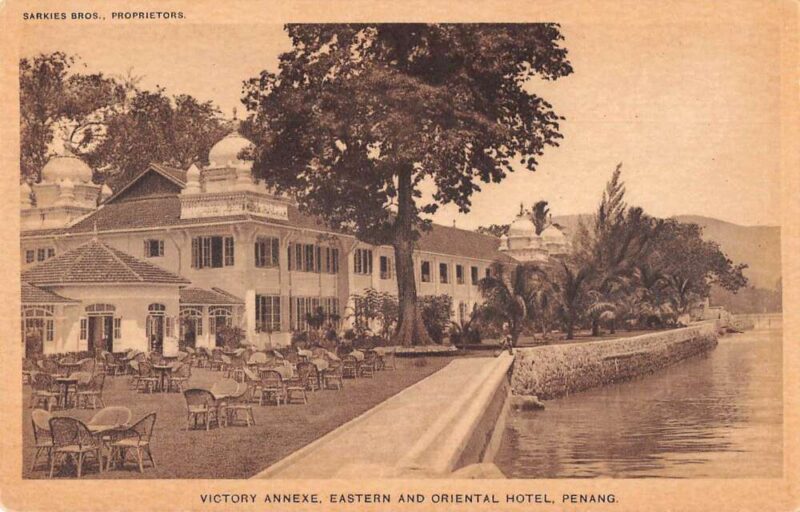

The letters begin in 1933 when the young British accountant Arthur Buckle shipped from London to Penang to work for a firm responsible for various enterprises, principally rubber estates, tin mines and hotels. He wrote regularly to his parents, especially to his mother, and as much as possible helped them financially during those years of the Great Depression. In 1938 he married Edrys. War came while they were on leave in Australia. Arthur served first in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserves, narrowly escaped from the Japanese invasion of Java, and was assigned to Melbourne Allied headquarters to work on codes and ciphers. Daphne was born in Melbourne in 1942. After the war — “this appalling muddle,” he called it — Arthur with his wife and three little girls returned to Penang. Singapore and the Malaysia peninsula were increasingly in turmoil; even the children knew there was a “heavy revolver on the chest of drawers.” When Daphne was nine, they immigrated to Canada, and she did the rest of her growing-up in West Vancouver. All this while, Arthur was writing regularly to his mother, and then after her death, to his father very far away in England.

Now his letters and Marlatt’s poems are able to evoke how it was — for him as a British businessman, for her as a child, and for some of the people among whom they lived. She writes: “Anglo managers came and went / industrial tappers stayed / lighting prayer lamps.” He describes, at the end of a road “a marvellous bungalow” and we recognise a scene that might have been imagined by Grahame Green or Francis Ford Coppola.

Time flows. Sometimes she re-imagines his milieu, as he fits into the Anglo society while learning the non-Anglo language. Other times, she recreates her own memories, occasionally looking ahead to the time when she would be looking back. The poem “Topical & Tropic” takes off from Arthur’s worried words written in Penang on March 20th, 1935: “Surely the Nations of Europe are not so crazy as to allow themselves to become in another futile recurrence of 1914!” while around him “the angsana trees are becoming a blaze of yellow blossom.” Eighty-five years later in Vancouver she writes:

you in blossom shadowed

by incoming historic

mechanization’s pall

while spring mountain

illumines dark harbour water the way

we turn our eyes

from eco-consequence to

what’s here here &

now

By early 1936, Arthur’s “British Community” was “incensed” by the “Italian methods of frightfulness” being used in Ethiopia. Marlatt’s phrase is “temporal irony” as she addresses him “still trying to see/ where you are.” He was learning about machine guns as Japan pushed further into Manchuria. The “eco-consequence” of climate change overtakes her “days of/ history intensified” and today’s “oil wars, drought & famine/ fished-out parts of ocean/ coral die-off, Arctic thaw.” In the 21st century her birthplace has become “Australia burning.”

Marlatt remembers her father showing “a curiosity about people of the various races and cultures he encountered in Penang, and often an empathetic attitude towards them.” Similar curiosity and empathy characterizes her poetry. As a child, she is aware that the people around her, even, especially those closest to her, have lives of their own. In Canada, her little sister wants “to mail her snowball ‘home’ so / Eng Kim could see it.” This poem, “En Route,” pays tribute to their young caregiver:

Eng Kim so much

more than child memory older than us though

still a teen employed to look after three high-

spirited daughters Eng Kim’s serious mild voice

stern because shy because young reserved in

high-button samfu showing me how to pronounce

Malay translations of English nursery rhymes

occasional laugh surprised hand to mouth bowing

out of family snaps aware of her place in both

senses Eng Kim worried more than we knew by

querilla kitchen talk her quiet fury at my sister’s

piqued toss of snatched keys into twilit jungle

Then there was Amah who “ruled the kitchen, wise-eyed & laughing, cleaver raised.” Marlatt recalls the love, the “consoling hugs,” and realises they did not know her name, her home, whether she had children. She was “Amah known & unknown,” and years later on a return visit these former children learn “we were your children too.”

British subjects working in the tropical reaches of the Empire were encouraged to go “home on leave” at regular intervals of three or four years, partly for health reasons, partly as a reminder of who they were and whence they came. A considerable chunk of the time was taken up by the sea voyage, and in 1937 arrangements for ports of call depended on “whether our dear friend Mussolini is behaving himself.” Arthur could choose not to return to Penang, but he did return. The work and the place suited him, and there were perks: “To be able to take several days off & toddle down to Singapore — to be able to live up here on the Hill in most delightful surroundings as we are now doing — these are things that are available (in different terms of course) to but a privileged few in London.”

how to be?

at home / ada di-rumah

“Ada di-rumah” meaning “I am at home.”

But things took “a more serious turn” as tension between Chinese and Japanese played out among the Malays. “ripple effects along the long/ South China Sea news line / massacres at Nanjing/ still homeland capital to many / Perankan.” Arthur was in one of the volunteer infantry units. He wrote: “This damn business of holding up the British prestige in front of the other countries is a blight! who would be a ruddy Empire-builder?” Still, the Penang Choral & Dramatic Society staged a comic opera. Then he fell “heavily in love.” With tenderness Marlatt imagines her parents meeting “on the brink of global change,” needing to make rapid decisions, working out who they would be, realizing there would be “ripples of aloneness” from his mother in England: “two separate people take books, letters to write on their/ honeymoon’s first flush, sharing the long stretch of / coupledom ahead // both doubtful and committed.”

As Marlatt tries to understand why her father returned to Penang after the war, why he stayed until there was no choice but to leave, she senses something beyond nostalgia, something to do with history and time.

Under the imposition of British imperial rule, a long prior history you

knew something of, confiding to me how you felt in a past life you’d been

a Chinese spice trader sailing your junk through the South China Sea to arrive

here, what was it?

Besides “company loyalty,” real though that was, was an atavistic insight into “the entre of entrepot” or “this entre of preneur” for a man “entranced by the betweenships of peoples sea derived.”

The final section, “Memory Montage,” gathers into “a fractured complex” her early memories of Penang with later images of return visits and past and present views of Vancouver. In a grocery at Keefer and Gore in Chinatown she finds a jackfruit:

but jackfruit ah jackfruit’s another story shipped from Malabar

chakka migrating east through trade for centuries to this northern

Chinatown street

weighed in the hand nangka’s heft signals an otherwhere soil as

jackfruit lingers on fingers gutting seed from fleshy pockets of

memory’s sundressed child under sun’s heavy hand this grown

hand lifts plastic-wrapped portions set of white mini trays of

Styrofoam

How wonderful is it to be a poet and invent such useful and meaningful words as “otherwhere” or “betweenships”? Marlatt takes full advantage of her licence to play with words and syntax so as to conflate time and sense.

As children, she and her sisters “didn’t get it didn’t have a clue about social erasure or the / silences of this Canadian city we had just entered.” The allusion to the Indigenous history (also “seagoing”) is more than that, considered in the light of Marlatt’s CV. It is also a signal of the sort of empathy she attributes to her father and which she herself demonstrates in this and other works. Aware of the horrors of war and its aftermath, she became an effective advocate for the Japanese-Canadians who were displaced and interned during those same years in which China and the Malay peninsula fell and suffered, while she was busy being a baby. It is “a fractured complex.”

Recently I heard the Canadian Islamic scholar Ayesha Chaudhry, author of the Colour of God, express regret for “our inability to save our parents.” The phrase comes to mind as Marlatt accompanies her father along their “verbal pathways” — the title of the final poem in this rich volume. She finds a way to “open memories closed roads” and continues asking “& what was home?”

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve was born in Fiji and moved to Canada at the age of four when her father died. Her book On Fiji Soil; Memories of an Agriculturalist is based on his letters and journals. She writes about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. She co-founded the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina on Gabriola Island. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has also reviewed books by Ayesha Chaudhry, Sylvia Olsen, P.K. Page, Peggy Lynn Kelly & Carole Gerson, Iain Lawrence, Michael Kluckner, Jack Lohman, Mona Fertig, Lara Campbell, and Ken Lum, among others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1153 Home on leave from Penang”