1085 A balanced cultural herstory

Hearing More Voices: English-Canadian Women in Print and on the Air, 1914-1960

by Peggy Lynn Kelly and Carole Gerson

Ottawa: Borealis Press, 2020

$24.95 / 9781896133713

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

As a library school student in the mid 1970s I was told that Anne of Green Gables could not be considered a Canadian classic; it just did not meet the standards. I read my first Montgomery novel when I was seven or eight and have continued ever since. Along the way I realised that not only had I found kindred spirits in Anne and Emily, but I was also being ever so gently educated: immersed in the era of my mother’s girlhood, introduced to the two major political parties (Mrs. Rachel Lynde, you may recall, was a Grit), and in Rilla of Ingleside provided with the foundation of everything I would ever learn about the First World War. Nevertheless, said these academic guardians of KidLit, what Lucy Maud Montgomery wrote was not classic. The very success of her novels was, as Kelly and Gerson put it, “viewed as symptomatic of their lack of serious value.” Fortunately, my degree and career did not depend on my acquiescence. Nor has Anne succumbed beneath their scorn. She reappears every couple of years in a variety of formats and adaptations, most of which I don’t like. At least, I think I don’t like them; I don’t watch them, because I have the book. Having made that assertion, I should confess that I first encountered Anne in a radio series — probably the 1944 BBC version — very early in my reading career.

As a library school student in the mid 1970s I was told that Anne of Green Gables could not be considered a Canadian classic; it just did not meet the standards. I read my first Montgomery novel when I was seven or eight and have continued ever since. Along the way I realised that not only had I found kindred spirits in Anne and Emily, but I was also being ever so gently educated: immersed in the era of my mother’s girlhood, introduced to the two major political parties (Mrs. Rachel Lynde, you may recall, was a Grit), and in Rilla of Ingleside provided with the foundation of everything I would ever learn about the First World War. Nevertheless, said these academic guardians of KidLit, what Lucy Maud Montgomery wrote was not classic. The very success of her novels was, as Kelly and Gerson put it, “viewed as symptomatic of their lack of serious value.” Fortunately, my degree and career did not depend on my acquiescence. Nor has Anne succumbed beneath their scorn. She reappears every couple of years in a variety of formats and adaptations, most of which I don’t like. At least, I think I don’t like them; I don’t watch them, because I have the book. Having made that assertion, I should confess that I first encountered Anne in a radio series — probably the 1944 BBC version — very early in my reading career.

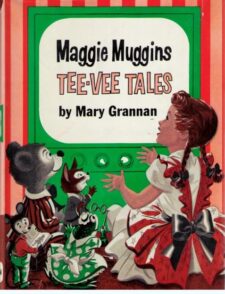

All that is by way of explaining my excitement over this contribution to the Early Canadian Women Writers Series. Not only do Kelly and Gerson repudiate this rejection of Anne by the same authorities who shocked me thirty years ago, but they devote many pages to another of my long-lost favourites: Mary Grannan. “Just Mary” on the radio cheerfully accompanied our Sunday lunch, right after Allan Mills sang folksongs, including his own classic, “I know an old lady who swallowed a fly.” Mary and radio were meant for each other, and I loved her stories long after I should have outgrown them. She published them as books, and I still wonder who better rendered the sound effects of my favourite, the train tale “Three Forty:” Mary at noon on the radio, or my mother at bedtime. Grannan’s Maggie Muggins brightened weekday suppertimes. Kelly and Gerson mention the moralistic epigrams which conclude many of her episodes, but what I recall is Maggie’s forward-looking exit: “I don’t know WHAT will happen tomorrow.” Grannan reappears throughout Kelly and Gerson’s book as a major talent in creation, production, and promotion of stories for children, as well as an educator, but of course her work could not be a “classic” and in 1962 was axed from CBC radio and TV as “out of date.”

I had imagined that no one but me remembered Just Mary and Maggie Muggins or had been shocked by the denial of classic status to Anne, so my excitement carried on throughout the book. Am I excited only because of my age? I hope not. The authors are distinguished scholars and the book a product of intensive research, its final 100 pages devoted to notes, bibliography and index. It is also a book of discovery. They intend to “discuss selected aspects of the lives and works of Canadian female writers and broadcasters within a tumultuous period during our socio-economic and political history: 1914-1960” focussing less on the better-known than the under-recognised, to show that the perceived need for Margaret Laurence, Margaret Atwood, and Alice Munro to invent themselves from nothing was a mis-perception; it was not a fact that no Canadian women writers existed after Susanna Moodie until they came along.

During the 1930s and 40s women writers and students were encouraged to look to foreign authors for precedents and inspiration; while their own immediate predecessors, even winners of the Governor-General’s awards, were dropped from anthologies and allowed to vanish from Canada’s literary landscape. But the book is also a celebration of the women’s resourcefulness in getting their words to their audience in the face of contemptuous dismissal by such distinguished authorities as Desmond Pacey, Northrop Frye, E.K Brown, and F.R. Scott. Scott’s “well-known misogynist squib ‘The Canadian Authors Meet'” they find particularly galling. Chosen by Margaret Atwood as late as 1982 for inclusion in The New Oxford Book of Canadian Verse and still widely admired online, the “squib” lampoons the Canadian Authors Association.

Scott as poet may not have had much need of the association; he was also a lawyer, constitutional expert, and — of course — intellectual. But many writers did need help if they were to write at all, let alone publish. And many still do. The website explains: “Canadian Authors Association is — and always has been — a membership-based organization for writers at all stages of their writing careers: aspiring, emerging, and professional…. As one of only 27 Registered National Arts Service Organizations with charitable status, much of what we do benefits all Canadian writers, whether they are members or are affiliated with us as partners or through other writing groups.” The Association published the Canadian Poetry Magazine from 1936 until it merged with Canadian Author and Bookman in 1968. I have beside me a copy of Vol. 23, No. 3 (Spring 1960). I admit that of the forty poets published therein, I recognise, besides myself, only two, both male: John Robert Colombo, who did go on to prosper although his accomplishments as editor and anthologist are better known than his poetry, and the tragic Roy Lowther. The others, including myself, did something else with their lives. But we had an outlet in which to test ourselves; we were even paid one cent per word. The “In Brief Review” section made us part of a writing community. That community mattered to the women of this book.

In Chapter 1: “What Matters as Literature? Women Writing fiction” the authors are almost gleeful as they recount the story of women who coped and evolved. Some “consummate professionals” such as Montgomery and de la Roche “exploited the burgeoning demand for periodical literature and popular fiction, especially in the USA.” Many women “whose writing sustained a wide range of Canadians periodicals and publishers … were considered inconsequential to the elite that judged what mattered as literature.” Within the “critical canon-forming decades of the 1960s and 1970s” they point to the Literary History of Canada (1965) as “symptomatic of the overall mindset and the normative gender inequity of the era,” and refer to “sanctified female fiction writers” such as Margaret Laurence and Adele Wiseman, playing here and throughout the book on the two meanings of “canonized” — works accepted into the official body of writings and persons revered as literary saints, in both cases sanctioned by authority.

Female scholars have to shoulder some of the blame. When Second Wave feminism celebrated such stars as the Margarets Laurence and Atwood, Alice Munro, and Carol Shields, they made little effort to recuperate earlier women writers of the 20th century. If those women had not been treated seriously by earlier, mostly male academics, they were outside the purview of feminist scholars. They wanted books by women to resemble books by men, to be written in the mode of modernist realism, to perpetuate the Canadian traditions of landscape art and a garrison mentality.

Instead, the neglected novels tended to “address many anxieties of the modern era as represented in their depiction of women’s bodies, minds and daily lives,” to be “driven as much by character and plot as by social purpose, and to address “key aspects of female experience in a Canadian context.”

Besides Montgomery and a few writers I was aware of from my mother’s reading or from their later work, such as Grace Campbell, Mazo de la Roche, Gwethalyn Graham, Gabrielle Roy, and Constance Beresford-Howe, a number of others are profiled by Kelly and Gerson. I am naming them for your convenience when searching used-book stores and because it is time they were named: Joyce Marshall, Martha Ostenso, Christine van der Mark, Winifred Bambrick, Evelyn M. Richardson, Jessie Georgina Sime, Irene Baird, Laura Gordman Salverson, Madge Macbeth, Flos Jewell Williams, Mary Coad Craig, Isabelle Hughes, and Katherine Roy. Writers of crime novels were doubly disqualified, but here they are: Frances Shelley Wees, Mabel Broughton Billett, and Margerie Bonner (a.k.a. Mrs Malcolm Lowry).

Poetry, even more than fiction, could not tolerate more than one canonical style at a time. The “gradual acceptance of modernist free verse as the literary norm … entailed the rejection of traditional rhyming verse.” The poets profiled here might be published in magazines, yearbooks, and chapbooks, but were dropped from more “serious” anthologies.

As a long-time student and devotee of modernism, I should probably plead guilty, but I am not sure. I do think there is good poetry and bad poetry, and the distinction does not depend on form or subject, or gender of author and/or reader. What it does depend on remains unclear to me; I agree with Emily Dickinson: “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” Kelly and Gerson make no effort to answer this question, and as feminist historians are more interested in the poets than the poetry.

They admire Edna Jaques, the poet of the everyday, whose “education had ended at eight, yet she taught herself … to write poetry which was accessible to everyone regardless of their education” and “channelled her creativity into entrepreneurship.” She “sold her rhyming poems to newspapers and magazines for anywhere from one to ten dollars … before collecting them in books that appeared regularly from 1935 to 1953.” Critic E.K. Brown, who took seriously his perceived “responsibility for disseminating literary standards” and duty to convince Jaques’s wide readership that they were misguided, wrote: “The critic need concern himself with mediocre literature only when he has before him a book to which the reading public, or a substantial fraction of it, is disposed to assign a false importance. Mrs. Edna Jaques’s My Kitchen Window is such a book.” Such breathtaking arrogance perseveres, of course, and can work both ways, rejecting experimental and contemporary poetry as deliberately obscure and therefore elitist.

Other poets rediscovered by Kelly and Gerson include Anna Minerva Henderson, a descendant of the Maritime’s Black Loyalists, whose poetry presents as more overtly Christian than Afro-centred, but universal in a gently beautiful line, “A late moon rises over one tall hill.” Bernice Loft Winslow/ Dawendine worked with the differing dictions and rhythms of her two languages, English and Mohawk. Eugenie Perry, “a well-rounded professional” extended beyond her poetry into activism on behalf of the hard-of-hearing and deaf community, as well as to authors’ organizations. The beautifully named Ethelwyn Wetherald took nature as her muse and did for a while make it into the Oxford Book. Others still in the anthologies are Anne Marriot, P.K. Page, whose reputation is still going strong, and Audrey Alexandra Brown (author of “A Dryad in Nanaimo”).

More excitement livens these pages than I can convey here. The section “Competing Modernisms” within the poetry chapter, lays out the debate between Mary Elizabeth Colman (1895-1958), who was Christian and anti-communist, and Dorothy Livesay, whose “Day and Night” Colman found a “clever piece of rhetorical propaganda.”

Dorothy Livesay (1909-96) became a Presence. In this book, she stretches across chapters from her early Imagist poetry into political and social poetry and dramas and radio documentaries. By the time I encountered her in the early 1960s she would stride into a room and inspire awe in those assembled, particularly the younger poets. I don’t remember what she read, although I am pretty sure it was socially and politically conscious, but I do remember the stride. Both proletarian and academic, she could be contemptuous of contemporaries who lacked her breadth. Reviewing Eugenie Perry’s “Hearing a Far Call,” a long poem that narrates the struggle for fulfillment of a woman through two marriages, a career on the stage, and traumatic loss during the Holocaust, Livesay dismissed it as “hampered by her choice of a sentimental wornout theme.”

Livesay and Marriott were among the many poets associated with the journal Contemporary Verse, edited by Alan Crawley. Kelly and Gerson firmly dedicate a section to Crawley’s wife Jean Nairn Crawley (1894-1972) whose contribution to the journal has been “downplayed by her contemporaries and by literary historians.” They assert, “As scholars of Canadian literary, our role is to challenge the tendency of the historical record to excise” such contributions as those of Crawley, Margerie Bonner-Lowry, and Dorothy Duncan (Mrs Hugh McLennan).

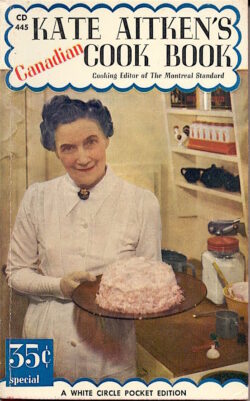

Chapters 3 and 4 examine “Women on the Air,” beginning with a brief history of radio broadcasting in Canada before launching into the role of radio in women’s lives. For many women then and now, radio has been the first source of news of public affairs and world events. Once again, Kelly and Gerson remind me of long ago treble voices in a time when the deep male voice was the standard. Kate Aitken and Claire Wallace were regularly heard in our home. For a long time the CBC’s policy allowed only one woman on the board at any one time, Nellie McClung being the first. I like to know that “in 1924 author Madge Macbeth wrote and produced a comedy titled Superwomen for CNRO in Ottawa. Later Ann Padlo became the first Inuit woman to broadcast on the CBC, Mary Todd Peate introduced Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique to Canadian women, and media-critic African-Canadian Kathleen (Kay) Livingstone coined the phrase “visible minorities.” Mary Grannan has a long lively section to herself. Discussion of Dorothy Livesay’s docudrama Call My People Home, about the experience of Japanese Canadians, includes a fascinating account of her involvement with production details.

When television arrived, the struggle began all over again.

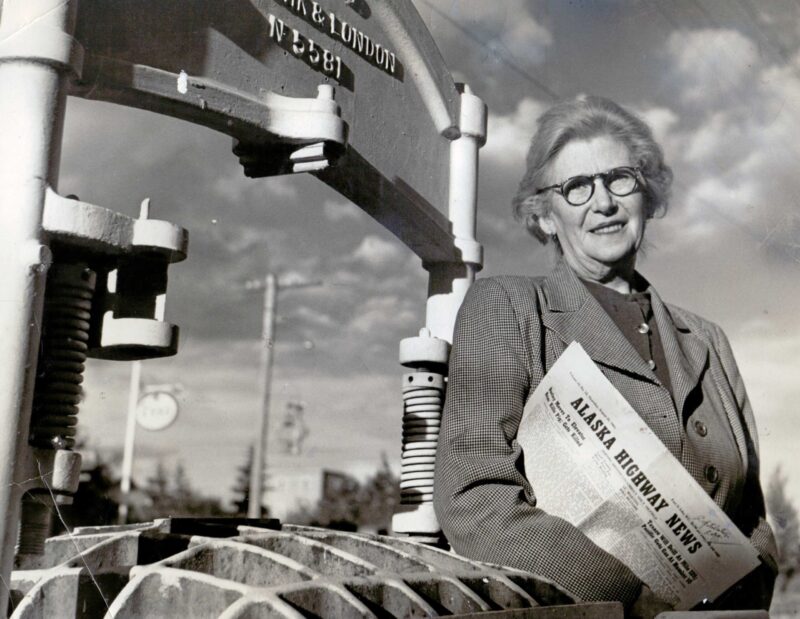

Chapter Five, “From History to Humour; Women Writing Non-fiction”, takes on the genres of journalism (including Doris Anderson, June Callwood, Simma Holt, Maisie Hurley — and Ma Murray, feisty editor of community newspapers in the BC interior; literary non-fiction (Laura Salverson, Emily Carr, Marjorie Wilkins Campbell, and Dorothy Duncan McLennan), as well as humour and issues of ethnicity.

In their conclusion Kelly and Gerson remind us that from “1914 to 1960, Canadian women writers were busy making a living and making literary culture.” At the same time, “middlebrow fiction, poetry and mass-media productions … were devoured by the reading public and were well received by like-minded reviewers,” if not by keepers of the critical canon. One of the authors’ messages is that it is okay to be middlebrow. This is reassuring as most of us are middlebrow in daily life, even if we can be highbrow when sufficiently challenged. That useful publication BC Bookworld proclaims on its website: “We aspire to middlebrow usefulness.”

As cultural historians, Kelly and Gerson have no use for either highbrow arrogance or middlebrow suspicion. They conclude: “Hearing More Voices: English-Canadian Women in Print and On the Air, 1914-1960 addressed significant knowledge gaps in Canada’s cultural history, yet much more recovery work remains to be undertaken. One of our goals in writing this historical survey is to inspire future researchers to proceed further; upcoming generations of readers deserve a complete and balanced account of Canadian cultural herstory/history.”

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications, including the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has reviewed books by Iain Lawrence, Michael Kluckner, Jack Lohman, Mona Fertig, Lara Campbell, Connie Greshner, Ken Lum, Ian Hampton, and Robert Amos, among others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1085 A balanced cultural herstory”