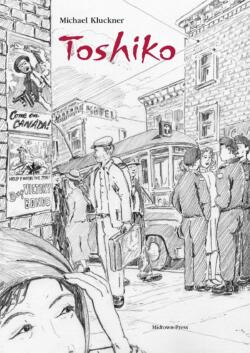

1049 A wartime internment romance

Toshiko

by Michael Kluckner

Vancouver: Midtown Press, 2020 (new and revised edition; first published 2015)

$19.95 / 9780988110175

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

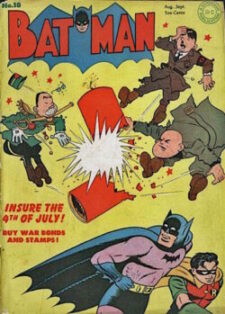

A graphic novel about the wartime treatment of Japanese Canadians? Well, why not? After all, my earliest reading about the Japanese was in comic strips and the weekend newspapers. Terry and the Pirates, Batman, even Andy Panda fought against this grotesquely toothy enemy.

A graphic novel about the wartime treatment of Japanese Canadians? Well, why not? After all, my earliest reading about the Japanese was in comic strips and the weekend newspapers. Terry and the Pirates, Batman, even Andy Panda fought against this grotesquely toothy enemy.

The library cataloguing authorities assign Toshiko to the Genre/Form categories of Graphic Novels, Historical comics and Romance comics, and the book does demonstrate characteristics of these various overlapping genres; it is a graphic novel with a historical setting and quite a lot of not-so-innocent romance.

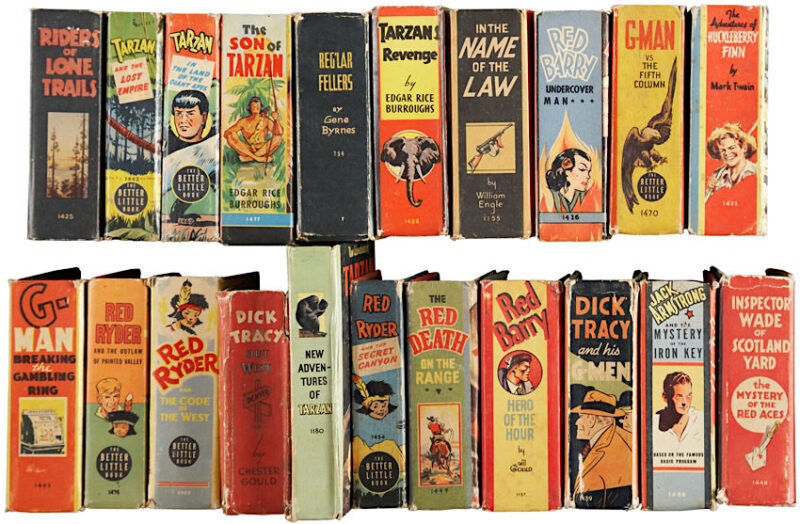

GRAPHIC NOVELS have been around since the 1840s, with a surge in popularity in the early 21st century. They augment the pictures and speech balloons with running narrative, but so did some of the comics and comic strips of my misspent youth, for instance the Classic Comics in which I previewed Wuthering Heights, Ivanhoe and Moby Dick before eventually going on to the full texts. Even some Sunday comics provided subtitles: for instance, Mandrake the Magician, who was constantly gesturing hypnotically, Flash Gordon, Invisible Scarlet O’Neil and especially Prince Valiant. I remember them well. Some made their way into bound editions, often as Flip Books or Big Little Books.

Many of these offered serious propaganda, because as Oscar Hammerstein wrote in South Pacific just a few years after the war, young people have to be taught how to hate. The American armed forces resorted to comic strip format to demonstrate “how to tell Japs [enemy] from the Chinese [allies].”

So it seems appropriate for Michael Kluckner to use comics, historical and romance, and the graphic novel to balance the scale away from hate towards truth and love. Masako Fukawa, who has written extensively about the Japanese-Canadian experience, reminded me that Daniel Shelton’s cheerful comic strip Ben, features mixed-race characters and frequently addresses the wartime story. Fukawa and I crossed paths when I was researching the Nikkei who once lived on Gabriola Island. It turned out her family had been among them.

So it seems appropriate for Michael Kluckner to use comics, historical and romance, and the graphic novel to balance the scale away from hate towards truth and love. Masako Fukawa, who has written extensively about the Japanese-Canadian experience, reminded me that Daniel Shelton’s cheerful comic strip Ben, features mixed-race characters and frequently addresses the wartime story. Fukawa and I crossed paths when I was researching the Nikkei who once lived on Gabriola Island. It turned out her family had been among them.

In 2011 Fukawa co-authored with Pamela Hickman an informative and bountifully illustrated volume aimed at 13-18 year olds, the same age group presumably targeted by Kluckner: Righting Canada’s Wrongs; Japanese-Canadian Internment in the Second World War (Lorimer: 2012). About Toshiko, Fukawa added: “Before it was published I was asked if it rang true to the internment experience. I was happy to see it as a graphic novel as it appeals to young readers. Perhaps to older ones too.” So this book comes with a meaningful endorsement.

*

MICHAEL KLUCKNER’S STORY begins in 1944 at Tappen, a farm community near Salmon Arm, British Columbia. Characters include a rich farmer and a poor farmer and a rich city aunt who holds the poor farmer’s mortgage and a cast of friends and (mostly) foes. The narrator, nicknamed Cowboy, comes from the poor family. His older brother is in the army, but Cowboy is still in high school and needed on the farm. He meets two Japanese-Canadian teens, Fiko and Fiko’s cousin Toshiko, who have been forcibly evicted from their homes on the coast and now live in shacks on the rich farmer’s land.

Romance ensues, facilitated by their school study of Romeo and Juliet. But it’s wartime and Japanese are the Enemy, even if they have lived in Canada all their lives. In an atmosphere of hatred, prejudice and hot tempers, there is a fight. This not being Shakespeare, no one is killed, but Cowboy and Toshiko flee to Vancouver to try to make a life together. He is willing to work at just about anything, and she looks “Chinese” enough to find a job in Chinatown. Their idyll is doomed by wartime regulations and bureaucracy: they are forcibly separated and he joins the army, which he is surprised to find himself liking. Toshiko and her family are banished farther east, to Toronto.

I am not going to tell you how the story turns out. There is a reunion, but not quite the one you might expect. This is not Romeo and Juliet, but it is a tragedy of sorts.

I am not going to tell you how the story turns out. There is a reunion, but not quite the one you might expect. This is not Romeo and Juliet, but it is a tragedy of sorts.

The first edition of Toshiko was published in 2015 and complemented by a teacher’s guide. This new edition contains ten additional pages, plus notes, index and bibliography, with an expanded explanation of the historical context, spiced up with more 1940s-style romance and adventure concluding with a more complete postwar wrap-up.

As I followed the novel through several readings, I increasingly felt that Class, even more than ethnicity, is the issue. For both races, Class, with accompanying shades of perceptions of respectability, economics and education, is the long-lasting barrier between the lovers and the reason for too many secrets which can never be told. The graphic novel format leaves a lot to the reader’s imagination, maybe too much. Am I reading implications not intended by the author?

Is the story of Toshiko and Cowboy what might have happened to Juliet and her Romeo had the star-crossed lovers not killed themselves? The Capulets and the Montagues reconcile only because of their shared bereavement. In this later version we have the official “reconciliation” between races, but not between the families.

Is the story of Toshiko and Cowboy what might have happened to Juliet and her Romeo had the star-crossed lovers not killed themselves? The Capulets and the Montagues reconcile only because of their shared bereavement. In this later version we have the official “reconciliation” between races, but not between the families.

Toshiko the girl is a stronger character than the protagonist. She knows what she wants and can be ruthless in getting it, even willing to live a lie. Cowboy makes a good life for himself, but often seems to prefer to be in a job where he is told what to do. I liked him much more than I liked her.

Kluckner’s fine line-drawings sensitively evoke the story’s settings, from the Thompson valley to Vancouver’s waterfront and Downtown East Side. Primarily an artist he is known for his renditions of the British Columbia landscape and city, especially their history. His favoured method for telling a story, making a point or advocating for a cause is through his pictures. Besides the first edition of Toshiko, he has created two other graphic narratives Julia, a biography of a little known heroine Julia Henshaw, and 2050, a “cli-fi” novel set in the ruins of Vancouver.

Kluckner’s fine line-drawings sensitively evoke the story’s settings, from the Thompson valley to Vancouver’s waterfront and Downtown East Side. Primarily an artist he is known for his renditions of the British Columbia landscape and city, especially their history. His favoured method for telling a story, making a point or advocating for a cause is through his pictures. Besides the first edition of Toshiko, he has created two other graphic narratives Julia, a biography of a little known heroine Julia Henshaw, and 2050, a “cli-fi” novel set in the ruins of Vancouver.

I was less taken with his portrayal of people. Sometimes I could tell them apart only by their clothing. Ethnic characteristics are not accentuated, except for the “cartoon” Japanese peering over the globe in the sequence about Pearl Harbor [spelt Harbour]. But even persons of the same race are not easily distinguished. This may be a deliberate playing down of differences, but does not always help the point. Or maybe it is the point. That Kluckner definitely can draw faces is witnessed by his other novels.

Like the Classic Comics, which were introductions to but not substitutes for the full narrative, Toshiko raises questions, suggestions, hints, with undertones complicated enough to lead to some serious thinking and more reading. We see Vancouver, the Fraser Valley, Kamloops and our own neighbourhood revealed as places where bad things happened. At the same time Toshiko is a coming-of-age novel that engages with the characters and draws the reader into a compelling story line. That the story is part of a larger and true story does nothing to lessen enjoyment of the “romance.”

Like the Classic Comics, which were introductions to but not substitutes for the full narrative, Toshiko raises questions, suggestions, hints, with undertones complicated enough to lead to some serious thinking and more reading. We see Vancouver, the Fraser Valley, Kamloops and our own neighbourhood revealed as places where bad things happened. At the same time Toshiko is a coming-of-age novel that engages with the characters and draws the reader into a compelling story line. That the story is part of a larger and true story does nothing to lessen enjoyment of the “romance.”

So our young person is attracted to Toshiko because it is a graphic novel, becomes engrossed and accidentally infected with history. Then they are ready to pick up Fukawa’s book, in which photographs tell the tale as drawings do in Kluckner’s. They may even be ready to set about righting Canada’s wrongs.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications, including the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: for The Ormsby Review Phyllis Reeve has reviewed books by Jack Lohman, Mona Fertig, Lara Campbell, Connie Greshner, Ken Lum, Susan McCaslin & J.S. Porter, Ian Hampton, Robert Amos, and Joe Rosenblatt, among others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1049 A wartime internment romance”