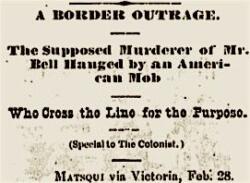

1421 A border outrage, 1884

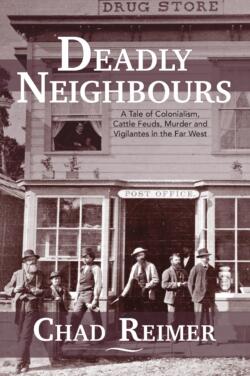

Deadly Neighbours: Colonialism, Cattle Feuds, Murder and Vigilantes in a Far West Valley

by Chad Reimer

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2022

$26.00 / 9781773860732

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

White settler injustice: racial tensions fuelled by two sets of laws, one white and the other First Nations

White settler injustice: racial tensions fuelled by two sets of laws, one white and the other First Nations

I’m a sucker for old dusters. The westerns where the good guys wear white hats and the bad guys wear black ones. Where the sheriff’s posse hunts down the lynch mob that has strung up an innocent man. Or where a judge and jury make the right decision in the interest of justice. You know the kind.

With Deadly Neighbours, we get a version of a Wild Pacific Northwest, and in this case it’s on the border between British Columbia and Washington. Author Chad Reimer has given us a more realistic image, one that is a long way from Hollywood.

The events take place in the mid-1880s in the region that covers Sumas Prairie, BC, and stretches into the Nooksack Valley in the United States. Here, on the American side, First Nations, mainly Semá:th (Sumas) and Stó:lō, try to co-exist with white settlers, many of them Civil War veterans.

Reimer provides gruesome details of several crimes including two murders allegedly committed by Indigenous citizens. We learn those details through Reimer’s careful review of court records.

Using them as his primary sources, we first learn about the murder of Nooksack merchant James Bell. Vigilante justice takes hold when a mob decides that the culprit is a 15-year-old Semá:th boy named Louie Sam.

“The lynch mob stopped two hundred yards north of the border and hanged Sam in BC,” Reimer writes, “making the Semá:th boy the victim of the only verified race lynching in Canadian history.”

What followed was a long road through the courts in an effort to learn the truth about the incident and bring the perpetrators to justice. But justice is not to prevail at least for Louis Sam and his family. Nor are the authorities on either side of the border going to expend much time and money proving the guilt or innocence of an Indigenous kid.

How the murder and lynching come about is one of the main focuses of the book. Through an almost forensic study of court records, testimony and newspaper accounts, Reimer takes us back to the scene of the crime and the miscarriage of justice. Along the way, we get snippets of the public response; white settlers openly nativist and hateful, First Nations angry but cautious. The latter was no stranger to white settler justice.

The New Westminster newspapers, the British Columbian and the Mainland Guardian, “parroted the line taken by the papers south of the line,” Reimer reports. Sam’s lynching was “shrugged off as an unfortunate incident.” The Whatcom Reveille was particularly vehement in supporting the vigilante mob. “The good people of the Nooksack and British Columbia disposed of the villain to the best possible advantage.”

It would only get more racist as the white population closed ranks around their own. “Their own,” by the way, were some vicious-sounding roughnecks who could have played any Hollywood bad guy with ease. Among the leaders was a family named Harkness. Reimer shows how they were often behind much of the violence that went unpunished, perhaps because the authorities feared reprisals.

Reimer also focuses on a second incident involving a young First Nations man in his early 20s named Jimmy Poole, a friend of Louie Sam. In another example of ruthlessness, a band of vigilantes seized Poole and accused him of horse stealing, a hanging offence in some states.

Without proof, the mob, some of them implicated in the Louie Sam lynching, mounted up and tracked Poole to a Nooksack chief’s house where they took him prisoner. Reimer notes that “there was general agreement that another ‘neck tie party’ might loosen Poole’s tongue” as to the identity of the horse thieves.

With that assumption, Poole’s abductors proceeded to hang him. “Two men pulled the rope, lifting Poole until only the tips of his toes touched the ground,” Reimer writes. “With the weight of his body hanging on the noose, the coarse rope cut into Poole’s neck, burning his skin, and his head started to throb from the lack of oxygen.” Poole, “gasping for air,” told the vigilante’s that he did not steal the horse and did not know who did.

The incident enraged the First Nations population, which weighed the possibility of exacting revenge with an armed uprising. Instead, Poole took his complaint to the courts. It was not a move the white population thought First Nations capable of doing.

“The arrests of the Nooksack Eight caused such rage across Whatcom County because Jimmy Poole’s action struck at the very hart of White society in the Northwest,” Reimer wrote. “An Indigenous man pressing charges against White men violated the care tenet that Washington was a ‘White man’s country, owned by and rule by White men for the benefit of them and their families.”

As the case was proceeding, the Knights of Labor, an organization that had been agitating against the Chinese with a view to expelling them, “insinuated themselves into the Jimmy Poole hanging case.” The Knights struck a committee to investigate with intent to prove the white perpetrators innocent.

The Poole case dragged on with two of the eight white men finally facing a grand jury. The result was “grimly predictable,” Reimer wrote. “None of the testimony mattered because the jurors had made up their minds before the case even started, and they had done so for one bald reason: that the victim and prosecution witnesses were Indigenous and the defendants White.”

Deadly Neighbours reveals the racist nature of white, especially American, settler society and shows that deadly violence can be part of the response to their Indigenous neighbours. What Reimer stresses, using the two cases, is that the white community has their law on their side.

It’s not a story that Hollywood westerns tend to tell in their romanticized versions of the Old West. We have Reimer to thank for setting the record straight by exposing the miscarriage of justice on both sides of the border.

*

As this review was being written, the U.S. Congress passed a bill making lynching a federal hate crime after more than a century of debate. The bill was named after Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy who was tortured and murdered in Mississippi in 1955. With Senate approval, the bill explicitly criminalizes “a heinous act that has become a symbol of the nation’s history of racial violence” (New York Times, March 7, 2022).

*

Ron Verzuh is a Canadian writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker. His work has appeared in The British Columbia Review since it was founded in 2016 as The Ormsby Review. Editor’s note: Ron’s book Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for Its Life in Wartime Western Canada, new from University of Toronto Press, is reviewed here by Bryan D. Palmer. See also here for Ron’s essay on trade unionist Harvey Murphy and here for a review by Mike Sasges of Ron’s Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb. Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Robin Winks, Tom Wishart, Janice Baker, & Lynn Campbell, Gregory Betts, Maureen Webb, David Lester, and Geoff Mynett. He lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1421 A border outrage, 1884”