1354 Vancouver avant-garde poets

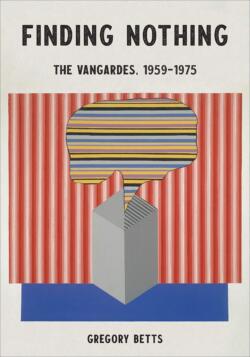

Finding Nothing: The Vangardes, 1959-1975

by Gregory Betts

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021

$85.00 / 9781487505318

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Vancouver Poetry Rocked in the 1960s. An Already Lively Poetry Scene Got a Jolt With the Arrival of the Americans

Vancouver Poetry Rocked in the 1960s. An Already Lively Poetry Scene Got a Jolt With the Arrival of the Americans

I’m a poetry fan. Whitman, Neruda, Frost, Akhmatova, Shakespeare, Atwood. Yes, Margaret Atwood before she was a world famous novelist. Robert Service, a favourite of mine. Who would not like Dangerous Dan McGrew? I could list many types of verse. Love poetry, political poems, Songs of Innocence, Songs of Experience. (Had to get Blake in there.) I even like the odd limerick when the mood is right. Yet I’m missing so many. Some of those missing pop up in a new book about a different kind of poetics called Finding Nothing.

Risky, titles like that. Readers who don’t follow the deep meanderings of the postmodernist and poststructuralist analysts of human activity may find nothing in this sweeping book about the poetry community of Vancouver in the 1960s and early 1970s. But those who persevere will turn over a story of some interest and value to understanding the cultural community of that period.

I’m somewhere in between. I can’t say I found nothing here, but I’m not exactly sure what I am finding. Here’s what author Betts wants us to find: “Finding Nothing addresses a scattershot array of sixteen years of experimental writing in Vancouver that reinvented the culture of the city and that has helped Canadians at large to re-imagine writing here and to bear witness to our internalization of colonial violence.”

In his conclusion, Betts adds, “What I am attempting to show here is that a significant portion of the Vancouver avant-garde poets embraced and explored doubt, absence and coherence — what I call the narrative of epiphany of finding nothing — directly in their writing.”

Betts discusses the Vancouver poetry world before 1959 populated by luminaries like Earle Birney, Emily Carr, Dorothy Livesay, Phyllis Webb and Malcolm Lowry. All of them made a huge contribution to Canadian literature. But his main focus, and he has done a brilliant job of reviving my many memories of 1960s poetry readings, is to explore the Vancouver invasion of two schools of American poetry introduced to Vancouver by UBC creative writing school founder Warren Tallman.

An American well connected to the United States poetry scene, Tallman invited poets from Black Mountain College in North Carolina epitomized by Charles Olson, a giant physically and intellectually, and the San Francisco school represented by Robin Blaser, Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley Jack Spicer, Gary Snyder and several others. Allen Ginsberg, of course, was at the height of his powers, representing the Beat poets.

These were heady times for poets and poetry lovers like me. Heady partly because much of the book covers the free love, drop out, smoke a lot of dope 1960s counterculture, but also because it stretches into the anti-war, “Question Authority” early 1970s. Heady, too, because these poets not only recited poetry, they performed it. They brought the words to life, peppering the air with them.

It was exhilarating to watch Ginsberg read from his famed social critique “Howl!” Enchanting to try to follow the deep exploring of the massive figure of Charles Olson reading from his Maximus Poems. Riveting to watch Robert Bly (later of Iron John fame) use his fingers like six guns as he recited verse that stood against the Vietnam War.

Back then, poetry buffs could also witness Russian poets swill Vodka and read poems to mesmerized young audiences on campuses. Celebrity poets like Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky regaled and shocked audiences with poetry about living in fear and defying it in Soviet Russia.

Betts’s period covers much vital ground during a period of upheaval throughout Canada. The Quebec separatist movement, women’s rights movement and youth movements were all part of a cultural revolution that was influencing the creation of poetry and song. Canadian nationalism had infused campuses across the country, sounding its horn against the Americanization of the country and its campuses.

I found it difficult to understand where Betts stood on all these matters and where he positioned himself in the poetry scene. Is he left or right? Or has he shunned those designations in favour of something else? Were the TISH poets political — George Bowering, Fred Wah, Frank Davey (the founding editor), Daphne Marlatt and many others? Or did they see themselves as above all that? Did the Vancouver “downtown poets” fill that hole? Were they the political activists while TISH and Blewointment poets like bill bissett and bpNicol were the revolutionaries?

Perhaps it’s unfair to root this discussion in a left-right dichotomy. Betts addresses it but he does not limit himself to one political ideology or worldview. Frankly, neither did many of the poets discussed in his book. All of us were sorting through the various permutations of that time. Some of us knew which side of the fence we were on; some of us knew who was there with us, as a 1960s poster once quipped. And some of us stood with the poets who wanted to make a statement about the dangers capitalism posed to the world.

What is clear about Betts’s analysis is his forthright condemnation of colonialism and the resulting displacement and destruction of First Nations people. He’s also crystal clear when he acknowledges the sexist TISH poets of the early years. He even provides a chart of how many women’s poems were published. Embarrassingly few. It improved, of course, because Vancouver’s women’s movement forced it to change.

Readers who lived through the period and were deeply touched by the New American poetry movement’s arrival in Vancouver will recall the excitement of the 1963 Vancouver Poetry Conference that breathed life into public poetry for a time. The conference was pivotal as a kickstarter to what grew into a movement of rival poets, publishing little magazines like Tish and Blewointment or the Georgia Straight Writing Supplement.

They made poetry exciting and colourful, but also at times nonsensical as the new Vancouver poets experimented with language and searched the physical properties of words and images. It had energy and it generated energy. Concrete poetry, cut-out poems and word inventions were all part of blasting out of convention. Here is how poet Patrick Lane explained the poetic collective consciousness of the times:

the voice of now is where we are

in Vancouver and the west is

tripping by itself on itself

catching the sunflower’s yellow

beautiful whispers and the poems

the thing no style no way of writing

no school no group NO THING is.

Lane captured the essence of Betts’s thesis with some clarity. Others were less clear. Some of the poets seemed lost, out-on-the-edge folks. Some also seemed cocky and arrogant as hell at times. They thought they were special and in some ways they were. Betts is honest in his depictions of aspects of that scene, but as he moves deeper into his probing analysis we lose some of the feeling of that modern heyday of Vancouver poetry.

Finding Nothing is an excavation site for a special moment in Canadian poetic history, but it will be lost on readers who just want to experience the beauty, insight and sensitivity of a well-crafted poem. Those who share a need for more analysis will be at home here. The people mentioned in the book will argue about what was included and what was left out. It is erudite, full of insider knowledge, and painstakingly persistent in covering the cultural scene. But it is not a book for the rest of us and maybe it wasn’t meant to be.

I struggled with this book, found it painfully thick, impenetrable at times. So I asked a poet friend to render an opinion. For him, Finding Nothing, though it was trying too hard at times and missed some of the key players, delivered an encyclopedic review of “the zoo of Poetry Vancouver and all its foibles and shamans and false messiahs and tricksters, some with enduring value and some long forgotten already and gone to the poets’ graveyard.” I could not have said it so well.

*

Ron Verzuh is a Canadian writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker. His work has appeared in The Ormsby Review since it was founded in 2016. He lives in Victoria. Editor’s note: Ron’s book Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for Its Life in Wartime Western Canada will be published soon by University of Toronto Press. See here for Ron’s essay in The Ormsby Review on Trade Unionist Harvey Murphy and here for Mike Sasges’ review of Ron’s Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb. Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Maureen Webb, David Lester, Geoff Mynett, Bonnie Henry, Bonnie Henry & Lynn Henry, Tim Cook, Greg Nesteroff & Eric Brighton, and Nick Russell.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1354 Vancouver avant-garde poets”

I usually can’t wait to order a book after reading one of Ron’s reviews. I have now read this review several times, and if I order ‘Finding Nothing: The Vangardes, 1959-1975’, it will be because of the comment attributed to a poet friend of Ron’s in his review > “the zoo of Poetry Vancouver and all its foibles and shamans and false messiahs and tricksters, some with enduring value and some long forgotten already and gone to the poets’ graveyard.”