Homesteaders: Alberta, 1905

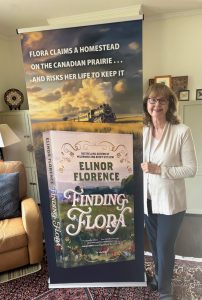

Finding Flora

by Elinor Florence

Toronto: Simon & Schuster, 2025

$24.99 / 9781668058916

Reviewed by W.H. New

*

Invermere writer Elinor Florence draws on southern Alberta history (and her own homesteading and Scottish/Indigenous family history) to tell this politically pointed story. Titled Finding Flora, her novel tracks the challenges facing women homesteaders in the early twentieth century. It centres on an Aberdeenshire character named Flora Craigie as she settles near Lacombe; and looking to the future, it celebrates women’s independence and also their achievements in the face of hardship and opposition. The book reads as a ‘political romance’—as distinct from a ‘romantic history’—but the author does not idealize hard work: instead, she stresses the challenges of isolation, gender discrimination, climate, fire, crop failure, social slighting, violence, and much more.

At the same time, the book’s narrative arc will seem conservative to some readers. While Flora’s bad marriage is followed by flight, distress, and discrimination, strength of arm and mind will sustain her as she finds her way to community and (in the closing chapters) respect and romance. I found the arc familiar, which may to some degree rise from the setting (Aberdeenshire and rural agriculture punctuate my own family history as well, though the circumstances of adaptation are markedly different from those in the novel).

For Flora, moreover, the challenge to adapt is not simply physical; it also involves habits that were formed by old-country notions of propriety, decorum, and ‘class’—all of which clearly get in her way. But she deals with them, and readers will applaud. Yet the achievement of the novel is, I think, less a matter of portraying a character named Flora than in relating the details of what Flora has to face: money, homesteading law, distance, seeding, men, children, threshing, water, and winter.

The novel begins with a leap into darkness—metaphor as much as trauma. Flora’s leap from a CPR train onto gravel, uncertainty, and as much anonymity as she can muster in a prairie town, is also a leap from a bad (and unconsummated) Scottish marriage with a malign (and syphilitic) ne’er-do-well.

He’s the snake in the grass who keeps trying to find her and upset her life (hence one reading of the book’s title); she’s the force of determination who, with the help of other practical women and a few good men, will over the course of a few years (1905-08) redirect political thinking (which constitutes another reading reading of the title). Flora has to find herself; she has to find community among other women, each of them in some respect an outsider—a Welsh widow with young children, an independent Métis woman named Jessie MacDonald, and an American couple in a ‘Boston marriage.’ And she has to cope with not only with the corrupt politics of money, land, race, and voting rights but also with her own Aberdeenshire biases about Old Country social mores: dress, language, appearance, family, and precedence. The Highland history of the Clearances—and of “Flora MacDonald’s Lament”—is close at hand.

Several historical characters enter the novel—among them Frank Oliver, William Van Horne, Alix Westhead, and Irene Parlby (not all of them lauded)—and Florence (Wildwood) attaches a useful reading list for readers interested in pursuing further the history of the 1872 Dominion Lands Act and the railway near Lacombe. In Flora’s narrative, the railway functions both as a line of communication and as a line of disclosure or recognition: it’s how Flora finds the anonymity she needs but also how she exposes herself to being located. And therefore applauded—or excoriated—depending on who’s doing the judging.

Finding Flora is mostly interested in the parallels between Flora’s growth as a farmer/settler/person and the emergence of her political voice. A community of women support her. Men, characteristically, are opposed to her: because she’s a woman who wants fairness as she strives to be an independent settler-farmer.

Those few males who are her supporters tend to be young (including a teenager who works hard and learns kindness), or professional (the doctor, another outsider in a way), or crankily independent. Those who oppose her tend to be rude, condescending, vicious, and manipulative. As Flora learns to handle them, she has also wrangles with the occasional woman who condescends. She admit that she herself can sometimes look down at others, mistaking surface for substance. Some men who speak gruffly and don’t necessarily look clean and neat turn out to be champions, some women with money and social status are more pretentious than virtuous, and children of all kinds begin to grow on Flora when she begins to accept that they too are individuals.

Race, gender parity, language: each encounter is political and each is complex. I don’t see any direct statement in the novel that this generation of 1905 children is the generation that will be shipped off to war in ten years’ time, but the implication is there in the account of changes in suffrage and franchise history. And in the several comparisons with the country left behind. The novel more clearly affirms that race relations in Canada could be better understood and that language is a changing medium. Flora speaks through much of the novel with her Highland accent emphasized and her disdain for nonstandard speech clear. As the novel proceeds, this distinction disappears into something approaching ‘Canadian standard’—this, too, is a statement of a kind about a process—perhaps about another political romance.

As a reader, I could wish that the earliest pages of Finding Flora relied a little less on effortful colour (“shards as sharp as needles,” “steel rails looked like two silver threads,” “treacherous… bitter… stubborn… spiky”) and conventional phrasing (“this landscape was an alien creature, bristling with hostility”; “The heavy clouds parted, and moonlight flooded the prairie”). Admittedly, these first pages are enacting Flora’s visceral response to her initial leap into darkness, so as a character she hasn’t yet learned an Alberta idiom. But I did not hear the early pages as Flora’s point of view, only as an authorial setup. And as I read the novel through, I realized how much more vivid were the later pages—those that sketched the dailiness of farm work, country fairs, community meetings, and chores. These later pages reveal the vigour of the novel. Finding Flora is most captivating there. And where many readers will come to appreciate Florence’s insights into the politics of community.

[Editor’s note: touring between towns and cities, Elinor Florence will be launching her novel April-June, 2025. Check the schedule of events here.]

*

W.H. (William) New has written five books for children, including The Year I Was Grounded (Tradewind, 2009), and he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. His most recent books include Neighbours (2017) and In the Plague Year (2021), reviewed here by Gary Geddes. [Editor’s note: William New has reviewed books by John MacLachlan Gray, Astrid Blodgett, Danial Neil, Yasuko Thanh, Carrie Mac, Corinna Chong, Robert Chursinoff, Harold Macy, Paul Sunga, Emily St. John Mandel, and Tamas Dobozy for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster