1937 Against invisibility

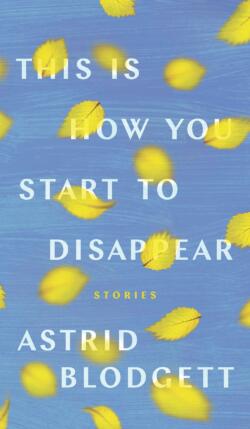

This Is How You Start to Disappear

by Astrid Blodgett

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2023

$24.99 / 9781772127133

Reviewed by W.H. New

*

The twelve stories that comprise This Is How You Start to Disappear are emotionally connected with each other. They don’t feature the same characters; they don’t ever quite resolve the dilemmas they each set up; they don’t develop through a single image or a narrow theme—so they don’t constitute a conventional sequence. But they do cohere, mainly because each of the stories reconstructs a moment in the early lives of its characters and explains why that moment continues to resonate later—not usually happily. The stories, for the most part, tell of some sort of continuing sense of restriction—of being unfulfilled, of not being given the chance to grow—despite whatever may otherwise be deemed a success. They hang on the moment when invisibility threatens.

The twelve stories that comprise This Is How You Start to Disappear are emotionally connected with each other. They don’t feature the same characters; they don’t ever quite resolve the dilemmas they each set up; they don’t develop through a single image or a narrow theme—so they don’t constitute a conventional sequence. But they do cohere, mainly because each of the stories reconstructs a moment in the early lives of its characters and explains why that moment continues to resonate later—not usually happily. The stories, for the most part, tell of some sort of continuing sense of restriction—of being unfulfilled, of not being given the chance to grow—despite whatever may otherwise be deemed a success. They hang on the moment when invisibility threatens.

In “Devil’s Lake,” for instance, a girl is taken skating, but she’s unhappy because her father, who has taken her to the frozen lake as a treat (his treat), will not exchange the skates that pinch her for ones that fit. Though she complains, she doesn’t resist. She says “I’ll be fine”—but that isn’t true—and the lie (the surrender to conventional order) colours all that follows: particularly her parents’ separation and her (dis)connection from parental substitutes. Another story, “This Will All Be Over Soon,” tells of a young girl who is cajoled into a ghastly date she’s neither happy with nor ready for: she’s covering up for someone else, trying to be who she’s not—“this is how you start to disappear,” the story muses. “I know I don’t need to say anything,” the girl says. But clearly she does.

Other stories follow suit. “Everything’s Fine, Actually” describes a childhood when roughhousing among siblings made a kind of sense—but then changes when gender norms call on characters to differentiate between what they know and what they say. Play can turn deadly, as in “The Fainting Game,” and loss is always close at hand, as in “How to Read Water.” A camp story titled “The Night the Moon…” tropes the difference between ‘this is what we did’ and ‘this is what happened.’ “The Golden Rice Bowl” (the only piece in this collection to leave Alberta and visit B.C.) spells out the difference between what is said and what remains unsaid. “When Sleep Is Easy” recalls a time when the title apparently made sense, but that was before being “unlucky in childbirth”:

“Nobody named the child in those days. Nobody held the baby. Nobody talked about the baby. That’s how it was then, not like now when everybody tells everybody everything, even strangers. She knew something wasn’t right about this but she didn’t question it, nobody questioned much then; she trusted that it was better to just try to forget. Of course she didn’t, she learned how to not talk . . .”

Silence might seem ‘sweet’ in some circumstances here, but talking, even constant talking (these stories characteristically represent dramas of insight through conversation rather than through overt action) is no guarantee of connection, nor of understanding.

Some readers may find the stories a little repetitive, in that they mostly spring from a similar premise: action is generally received or watched, and when generated (“Bri went to her closet”) leads only to closure. For instance:

Beth says Dad’s downright giddy. [potential action twice removed]

Kim felt it when she was drying him after his bath. [him at the centre]

Alex knocked me across the head. [narrator is recipient]

Bri went to her closet . . . [isolated?]

Sascha and Magalie were on an island. [separation, even if together]

Maddie wants to kick someone. [anonymity]

Cora massaged a tube of icing . . . [pre-packaged]

We drove to the pig camp on Thursday. [‘pig’?]

Aside from the difference in names, the measure of these story openings is much the same: a character is named, a character is established as the observer rather than the agent of experience. The apparent flatness of (most of) these gestures, however, seems to be a deliberate tactic, one designed to establish the norms that have governed the characters’ lives, which is to say the social normality of lost agency. How to Disappear depicts characters who have long been aware of being disempowered. Finding out when and why they were suppressed: that is their challenge, and usually it’s what they discover—but it doesn’t necessarily free them. Hence the apparent quietness of the stories is nothing of the kind: it’s a refusal to accept suppression. Reportage here is rage against disappearing.

For this reader, two of the stories stand out: “Dear Hector” and “These People Have Nothing.” The first of the two deals with a missing cat, but more than that, it confronts the abruptness of events in life, the moments when people die, things disappear, and the central character Maddie decides she doesn’t want to join the dance, she wants to leave it. Although “These People” addresses the killing of a dog, once again the characters resist the conventions they’re asked to accept: poverty and gendered roles, the opportunity to buy things and the idea of perfection. “I tried,” the narrator writes, “to understand how a person could be sad and angry at the same time and what I was angry about.” She’s angry about death, about death-in-life, about what she’s seen and what she thinks she’s seen, and about her mother, who (she realizes later on) has quietly taken upon herself the right to act.

In these stories Astrid Blodgett (You Haven’t Changed A Bit) resists flamboyance. But her stories are not quiet. They simmer with a grammar of discontent. Readers, listen closely.

*

W.H. (William) New has written extensively about the short story, as in Dreams of Speech and Violence and Reading Mansfield. His most recent books include Neighbours (2017) and In the Plague Year (Rock’s Mills Press, 2021), reviewed here by Gary Geddes. [Editor’s note: William New has recently reviewed books by Danial Neil, Yasuko Thanh, Carrie Mac, Corinna Chong, Robert Chursinoff, Harold Macy, Paul Sunga, Emily St. John Mandel, and Tamas Dobozy for BCR.]

W.H. (William) New has written extensively about the short story, as in Dreams of Speech and Violence and Reading Mansfield. His most recent books include Neighbours (2017) and In the Plague Year (Rock’s Mills Press, 2021), reviewed here by Gary Geddes. [Editor’s note: William New has recently reviewed books by Danial Neil, Yasuko Thanh, Carrie Mac, Corinna Chong, Robert Chursinoff, Harold Macy, Paul Sunga, Emily St. John Mandel, and Tamas Dobozy for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1937 Against invisibility”