1608 The vernacular of the country

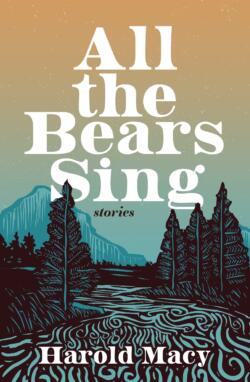

All the Bears Sing: Stories

by Harold Macy

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2022

$24.95 / 9781990776007

Reviewed by W.H. New

*

Readers who enjoy tales of living and working in the BC woods and in small Coastal communities will find much to appreciate in Harold Macy’s collection of 23 tales and stories. Macy writes out of experience; he writes what he’s clearly observed of places and people; he invites readers to experience both isolation and community, so as to share in the losses and the affirmations that sustain the lives he so much values.

Readers who enjoy tales of living and working in the BC woods and in small Coastal communities will find much to appreciate in Harold Macy’s collection of 23 tales and stories. Macy writes out of experience; he writes what he’s clearly observed of places and people; he invites readers to experience both isolation and community, so as to share in the losses and the affirmations that sustain the lives he so much values.

The title story, ‘All the Bears Sing,’ while one of the shortest sketches in the book, clearly conveys the flavour of the collection. It asks what you hear when you walk in the forest: how does the wind through the pines differ from the wind in the aspens? How does the sound of bears ‘at play’ — away from human interference — shape our understanding of their behaviour and our own, illuminate our values perhaps? The sound of ‘party boys’ in the woods is made to seem more dangerous than the sounds of animals in the wild, and as one detailed observation follows another, the reader senses how Macy distinguishes between the ‘presence’ that sun and forest bring to our lives and the ‘absence’ that is shaped by ‘clearing.’ The morality of ecological respect is never far away.

Macy early affirms that you can find sensibility even where you don’t expect it, and phrases such as the ‘feral fraternity of misfits’ tell you of the character of the people that absorb him. Those who leave for the Coast generally find a way back; those who stick it out among stumps and clearings find companionship and confirmation. More often than not, the lonely find help when needed: ‘the kindness of strangers’ is a recurrent motif, amply dramatized in sketch after sketch. Not that there aren’t disruptions — fire being one, loss a second, the presumptions of city people being a third — but even the guy with a nice car and nice city shoes can expect empathy as well as judgment, if he deserves it. Macy knows the vernacular of the country, and he uses it to effect; he also knows what ‘correct’ language sounds like, and what its impact is when it’s used to diminish and demean.

Portraying the natural world, Macy writes with a gift for ordinary eloquence, as when he speaks of a ‘community on the edge of public order’ or follows a logging crew through ‘a steep kilometre of sheltered forest,’ or finds in the midst of ‘wilderness’ a place for magic, a ‘sacred’ place that is inaccessible elsewhere: the rough does not exclude the spirit. Even as one of his characters is short-tempered, recovering from a fall, his inner sensitivity reveals itself. This is a world where the ‘bareback corduroy sea’ at once endangers and lifts those who kayak over it. It’s a world where even ‘the squeal of lonely, tired springs’ at the Princeton Hotel can offer comfort to the firefighter, and where gelignite and Victoria’s gardens can both be talked about with equanimity. It’s a world where the winter swans can rise from the foothills, then head ‘down to the beach to follow the retreating tide, claiming eyebrows of gravel and the feast of rich seaweed.’

Macy is at his best when evoking these moments: the experiences that have sharpened his eye have led to vivid glimpses of people and places. Less effective, I think, are the occasional narratives that attempt to shape dramatic scenes, as in the rendering of the trumpeter swan sketch as a love story, or in the longest story, ‘Overburdened,’ about geological exploration and the power of resistance. In his ‘Acknowledgements’ page, Macy thanks his editors for help in ‘polishing my rambling syntax’ and recognizing the need to ‘drown my kittens’ (a riff on Samuel Johnson’s celebrated advice, ‘Wherever you meet with a passage that you think is particularly fine, cut it out.’).

Sometimes a reader might wish for a little more streamlining, as in the first paragraph of the first story, in which early summer storms ‘frolicked a hellish two-step across the forested steeps,’ trailing fire up to a ‘jungle that has rarely felt this devil’s lick,’ steeps that had earlier experienced a drought that had ‘parched the forests into corn-flakes’ but now were dealing with a ‘swath of thunderbolts,’ an ‘umbilical’ power line, and ‘an angry swarm’ near a ‘blustery’ lake. If this overburden of adjectives dismays, read on: the book is far more engaging than its opening. I’d suggest starting almost anywhere else: each of the subsequent sketches is sharper and more alive.

*

W.H. (William) New is the author of Reading Mansfield & Metaphors of Form (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. New’s most recent books include Neighbours (2017) and In the Plague Year (Rock’s Mills Press, 2021), reviewed by Gary Geddes. Editor’s note: William New has recently reviewed books by Paul Sunga, Emily St. John Mandel, Tamas Dobozy, Rhonda Waterfall, Leah Ranada, and John MacLachlan Gray for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1608 The vernacular of the country”