‘Offering, loss, self-examination, and affirmation’

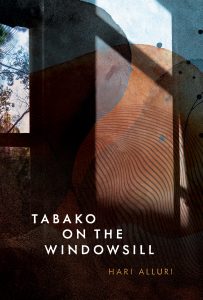

Tabako on the Windowsill

by Hari Alluri

Kingston: Brick Books, 2025

$23.95 / 9781771316491

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

This is a book about hiding. And smoking. And both at the same time. Which isn’t really hiding at all, but is hiding some things. It is about the crossroads between being open and hidden. It is about what is transient and what remains.

Fire, for instance, or “desire,” as Hari Alluri (The Flayed City) puts it in high literary style, is hidden, yet the smoke points to it. It’s a clever lyricism, as intertwined as threads of smoke itself: offerings and prayer that vanish into air but can be repeated as the symbolic and ritual Hindu hand gestures called mudras.

Of the dislocation it speaks to, Alluri writes, “The Cigarette is Pretext: Smoke Rises from Within.” Speech here isn’t in words but in the gestures they make. The words are cigarettes. You light them and they burn away into smoke. This book, a shrine, is Tabako on the Windowsill, right where inside and outside meet.

Alluri frequently hints at the origin of this smoke that humans breathe out. As a west coast Canadian of filipino and South Indian ancestry, he addresses his living conditions apart from his mother’s islands by noting in his poem “Windowsill Offering to Anagolay, Goddess of Lost Things,” “What I can tell you is which corner stores sell my brand / cheaper when I buy packs in pairs.”

This is not cynical. Alluri has migrated from ancestral lands to images of them, in a kind of poetry that proceeds by lyrical hints. For example, after calling up Saint Anthony he proposes a new goddess to the goddess Anagolay (he lost his medal of the saint and presumes she once hid behind his face, too). His new goddess is no goddess of lost things, nature and natural cycles, but a contemporary and humanistic one of “misplaced objects and forgetfulness.” Apologetically, he adds “no direct relationship [to you] / despite the life of lighters, to those / dimensional portals where you dwell.”

Clever. Neither the lighters nor the portals of the goddess are the things misplaced. Places are. And the relationship he mentions between smoker and goddess, although indirect, is not in any way denied. This hiding in plain sight behind a mask of appearances is lyrically sophisticated and supremely life-affirming. “I’m already running late,” he notes later in the poem, “and step back through the apartment door another time,” fully aware that Anagolay can find anything simply because “everything is tethered to … [her] …essence.”

So are Alluri’s fictions. There’s a whole series of poems in this book extending this language of offering, loss, self-examination, and affirmation. It is brilliant work, all performed (or burnt, to use his image) in language that both celebrates the strengths of English and extends them to include the smoke of others that offered to it.

A good example is the title of Alluri’s poem “When I walk in she’s mixing someone’s drink, hitting the notes on ‘How Will I Know,’ and later we together-laugh at an inside joke on us.” Here, language is both inside and outside, both mastered and merged with others.

The intertwining is not done without a sturdy self-awareness. “I sat down here to feel a distance,” he writes, and then notes “the distance in bodies who recognize // belonging feels like someone else’s music.” By this he nods to the rhythms of English he is writing in, and the song, “Que Sera Sera,” he listens to, that “bends the language [Spanish] that suppressed our tongues // 333 years.” Not now.

Nonetheless, what remains in these mudras is a brittle defensiveness, or at least self-protectiveness. In “Origin Story,” for example, a friend warns him that “if you lose yourself / in any one story, even a true one, / eventually you lose that story as well,” in “a universe of bodies // moving in relation.” In Alluri’s version of the global diaspora, it’s not place one finds, but the ability to give up stories to find their spirits. Crossroads keep forming, roads can (and must) be chosen but no ends are certain other than choice. You can’t stay. You have to go on.

The hurt of place is obvious when Alluri writes, in “Windowsill Offering to Anagolay, Goddess of Lost Things,” “And, because when it’s government behind the disappearances, whoever knows too much / will be who’s taken next, and those who remain wherever here might be for them / must make a semblance out of the partialities we have left.”

One of Alluri’s conjurations of smoke is to write ghazals, not the North American version as a tour-de-force conflation of Sufic and Buddhist and Modernist practice, but the Indian version, with its compulsive refrains of return and departure. Yes, like Anagolay.

A classically lyrical example of these ghazals is “Braided Ghazal [Rest],” which returns at the end of every couplet to a new intonation of the word “rest”—a new mudra, in other words.

A ghazal that explores turntable music instead is “Wunderkut Forever Ghazal,” with its compulsive repetitions of “wonder,” This one at times unfortunately misses the wonder within the word, yet the mouth music along the way is beautifully scratched by hand on a turntable, with its “Unmarked crown & royal. behind a counter. mixer. after. school. skipping / pantry in your chest. Your skratches, consonant. Mistakes? Raw wonder.”

Whereas that ghazal and other poems reaching into exercises doesn’t fully integrate East into West beyond the delight of the performance, “Poem to Burn” does, although by integrating West into East instead. Call it a broken ghazal perhaps. Or maybe a turntable ghazal. Whatever it is, here the timing slides sideways and spirals through the lines, avoids couplets and the dance movements of endings, buries rhymes within lines instead of dropping them hard at their ends, and twines like smoke out a window, or like a child learning to balance on a bicycle:

If my godchild throws her limbs in every direction trying not to fall

then falls and scrapes her knee, she might or might not

reach for a hand to pull her up. Legs back above the wheels

spinning at her feet. Next time I call, I’ll ask her if she still

names it when she falls down.

These are poems that attest in every moment to the strength that new ancestors, new techniques, and new understandings brought to British Columbia by migration, binding poetries of people in place to what looks at first as a large and scattered world but which is as intimate and close as the mudras of Alluri’s hands.

*

Harold Rhenisch has written thirty-five books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for a memoir, The Wolves at Evelyn. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack and Out of the Interior. He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and worked closely with photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass, Motherstone, Cariboo Chilcotin Coast, and The Bowron Lakes; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. Harold lives in an old Japanese orchard on unceded Syilx Territory above Canim Bay on Okanagan Lake. [Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has reviewed books by Brian Day, Jason Emde, John Givins, DC Reid, Kim Trainor, Dallas Hunt, Tim Bowling, Hamish Ballantyne, Zoë Landale, Kerry Gilbert, Robert Hilles, Sho Yamagushiku, Bradley Peters, Aaron Tucker,Dale Tracy, Dominique Bernier-Cormier, Selina Boan, Joseph Dandurand, Délani Valin, Robert Bringhurst, Rayya Liebich, Sarah de Leeuw, Roger Farr, Stephan Torre, Don Gayton, and Calvin White for BCR. Recently, his The Salmon Shanties was reviewed by Steven Ross Smith.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster