Excellent addition to the backpack

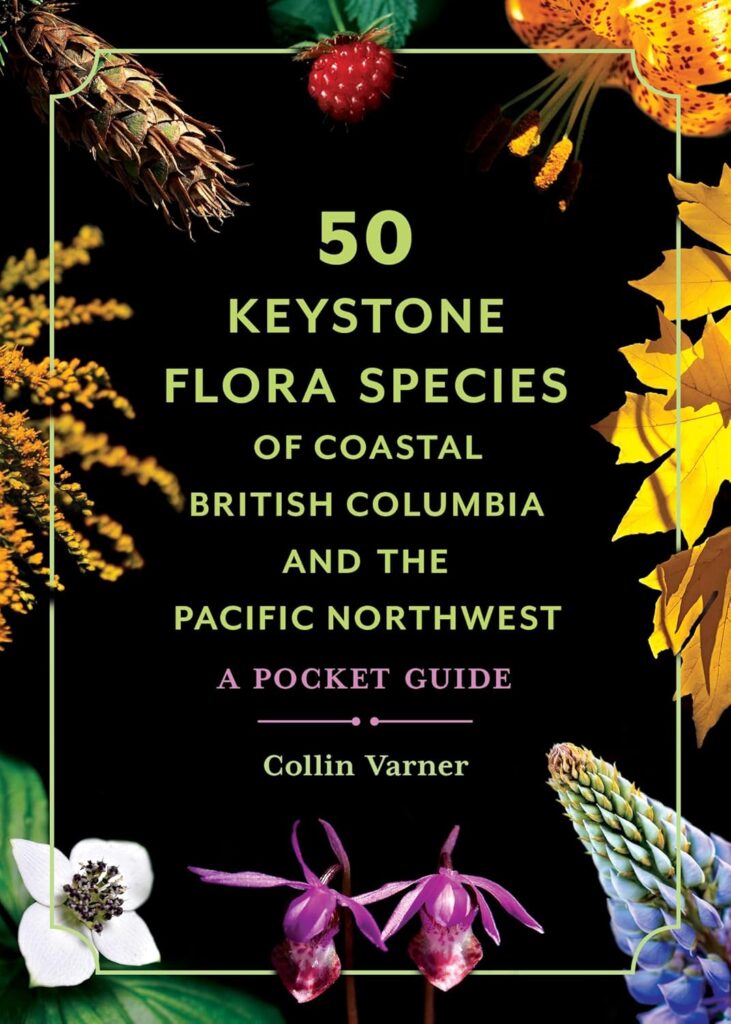

50 Keystone Flora Species of Coastal British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest: A Pocket Guide

50 Keystone Fauna Species of Coastal British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest: A Pocket Guide

by Collin Varner

Victoria: Heritage House, 2024

$19.95 / 9781772034776 / 9781772034943

Reviewed by Isabel Nanton

*

On a recent summer hike along Vancouver Island’s Cowichan River, we enjoyed referring to Collin Varner’s flora pocket guide to keystone species, “keystone” being organisms that define and support an entire ecosystem thus filling a vital ecological niche. On encountering a grove of Garry Oak (Quercus garryana), we learned that plant explorer David Douglas named this native oak after his friend Nicholas Garry, then deputy governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Meanwhile, the endangered role of once-prolific Garry oak meadows which “support thousands of species of birds, mammals, insects, mosses, lichen, trees, plants, and grasses” means that already gone are acorn woodpeckers, western bluebirds (in the Pacific Northwest), Lewis’s woodpeckers, and streaked horned larks.

Retired UBC tree conservationist Varner’s guide is a welcome addition to a backpack. Its well laid-out text on one page, with a picture opposite of the species (in one case a Quercus garryana trunk with acorn insert) makes for swift and easy identification in the field.

Last century, when I was compiling the Sierra Club Guide to British Columbia, we carried around the classic Pojar and Mackinnon’s Plants of Coastal British Columbia which includes many First Nations’ uses for the various species. For example, in the case of Garry oak, the Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest ate the acorns after soaking to leach out the bitter tannins.

What is appealing about Varner’s pocket guide, is the thought he has put into his selection of 50 species (out of a possible 700 plus in the PNW). Selected marine plants include mighty Bull Kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) forests which “supply a habitat and food source for more than a thousand species of marine life” and are “one of the most productive ecosystems in the world.” Varner’s own photos provide the majority of the illustrations, showcasing an author with a good eye plus a penchant for the telling detail – bull kelp, for instance, can attain lengths of over 30 metres (100 ft.).

Even the humble Oregon grape (Mahonia nervosa)’s blue berries, which visitors can spot in the wild as well as in urban environments like Vancouver’s Pacific Spirit Park, attract coyotes, cedar waxwings, raccoons and are a favorite browse inland for elk, deer, bears, and other herbivores. As for the blue-berried elder (Sambucus caerulea), Varner has seen “coyotes chase birds out of the bushes, bend the branches down and eat the berries, which can last into October.”

Space likely precluded the inclusion of a lichen species of which we saw many on our Cowichan River hike, including Common Witch’s Hair (Alectoria sarmentosa), a food for deer in the winter but certainly not as “keystone” as the 50 species Varner has selected for this pocket guide.

Meticulously researched, attractively laid-out, this flora field guide is wide in scope, a book which armchair travelers and veteran hikers can now consider essential kit along with binoculars on any exploration of the PNW.

*

Portable and full of interesting information, Varner’s companion guide to his 50 flora species is an absorbing read and even though most of us might not encounter an American mink (Mustela vison) or Cougar (Puma Concolor), merely reading about these two species convinces how crucial they are to the biodiversity of the ecosystems they inhabit. Being both terrestrial and aquatic carnivores, mink predate on so many creatures that the author argues “without this natural control” some of the creatures they eat “could overpopulate within a couple breeding seasons.” Plus, we learn the name mink is from a Swedish word that means “stinky animal.” Meanwhile, those apex predators, cougars and wolves, eat creatures such as deer in a landscape which would otherwise soon become overrun by grazing herbivores.

It is easy to enthuse about our creatures of the PNW and I was happy to learn that many of my favourites merit “keystone” status. Even the humble Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) is so important to the Canada lynx population “that the two populations are linked with a boom in the snowshoe hare population leading to a rise in the lynx population.”

Birds, frogs, bats, spiders, octopus, and other keystones inhabit the pages of this guide and I found myself nodding in agreement at Varner’s selection of certain species. Over 500 species of spiders live in the PNW, including the giant house spider (E. Duellica), goldenrod crab spider (M. Vatia) and western black widow (L. Hesperus). Selected is the familiar Cross Orbweaver (Diadem Spider Araneus diadematus) “most often seen at the end of summer and autumn, spinning their orb-like webs”, not only catching mosquitoes, flies, wasps, bees, moths, and beetles but also eating their own webs on a regular basis. This makes them omnivores, not pure carnivores.”

Another favourite apex predator of the night is the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), one of a dozen owl species in the PNW, who flies in absolute silence with a head that can turn 270 degrees. While who could not love the largest octopus in the world, the Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) who can weigh in at 124 kg (300 lbs) and eat about 5 kg (12 lb.) of food per day?

Skwxwu7mesh ethnobotanist Senaqwila Wyss introduces both pocket guides with First Nations’ reflections on our interconnectedness with nature, in the fauna guide sharing the Coast Salish Squamish concept of “one heart, one mind,” the Coast Salish Peoples’ worldview of “all beings and walks of life living in harmony with one another. Rather than seeing each species as an individual and standalone anima, we have always seen the gifts and roles that each living organism plays.” Asking the reader, “What can you do to give back to the forests, trails, waterways, and natural areas in both urban and wilderness spaces where you can continue to observe these beautiful animals and help them thrive?”

*

Kenyan-born author and Cambridge Press Fellow Isabel Nanton is author of the Sierra Club Guide to BC, Adventuring in British Columbia (Sierra Club Books, 1996, with Mary Simpson). She specializes in writing about East Africa and Western Canada. She has reviewed books for the The Globe and Mail, The Vancouver Sun, and Old Africa magazine in East Africa. Editor’s note: Isabel Nanton has also reviewed books by Robert Silverman, Lisa Duncan, Oriane Lee Johnston, Mary Bomford, Mellissa Fung, and John Schreiner & Luke Whittall for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Excellent addition to the backpack”