Adieu, Pnina! Well, maybe

Pnina Granirer:

Goodbye-Adieu-Farewell

Retrospective by Christina Johnson-Dean

*

Adieu, Pnina! Well, maybe. Although in March, prolific artist and writer Pnina Granirer, now age 89, had a sale of her art, supplies, and furniture from her home of 57 years in West Point Grey, she disclosed that in her new home at Tapestry Senior Residence she expects to keep writing. Brava! It’s not surprising for a woman whose extensive and well documented career has lasted over almost seven decades and exemplifies never stopping, even if she had to “lower the flame and let things simmer.” Though her years in Vancouver have been full steam ahead, her journey in life has wound through wartime, genocide, multiple moves and immigration, as well as the challenges of being a female artist in societies with an art world dominated by males though increasingly impacted by growing feminism and success. In 1998, Ted Lindbergh wrote Pnina Granirer: Portrait of an Artist, a thorough and beautifully illustrated book of her life and work. Yet now, over 25 years later, she has continued to add immensely to her story.

Born Paula (her grandmother’s name) Solomon of Jewish parents in the Danube port city of Braila, Romania in April, 1935, she was educated at a Catholic school and was known as the class “artist” with her abilities to draw and create posters. Her father, a certified accountant, was able to provide well for his family, and took them to the Royal Palace in Bucharest, which became the National Art Gallery. Though she did not fully understand the antisemitism of Romanians (which has been documented from at least the 12th century) and the heightened dangers when Nazi Germany came to dominate the country during the Second World War, she was aware of things being sinister and disturbing. Decades later, when she learned more fully of how fortunate they were to have side-stepped the worst atrocities of the times, she worked childhood charms of the devil and the angel into her art and has constantly examined, considered and struggled with on-going human efforts to cope with good and evil, light and dark. Though they initially welcomed the Russian liberators when she was ten years old in 1945 and her father remained employed, it became apparent that life was still restrictive for people of Jewish ancestry. They changed their surname to Savin, but there was pressure to join the Communist Party, and her father was nearly arrested when the communists took over the board of a cooperative store, ousting socialists like her parents. He went into hiding and was smuggled out of Romania and made his way to Israel. Her mother was forced to give up their house and found it necessary to divorce her husband in absentia due to the danger of being married to a fugitive. To some degree, Paula was aware of these difficulties and injustices. However, in 1950, she and her mother were able to immigrate to Israel due to a Jewish Agency (JOINT) which paid the Romanian government large sums for exit permits, essentially selling its Jewish citizens.

Israel was dealing with a huge influx of immigrants and her family struggled to make a living (truck driving, sewing, and for Paula painting Disney images on cuckoo clocks and lampshades – her first paid work using her artistic skills). They lived in a small studio flat in Gav-Yam near Haifa, but despite the privations, there were feelings of hope and exhilaration. At this time, she changed her name to Pnina, a Hebrew name, which means “pearl” (still acknowledging her grandmother “Paula-Pearl” after whom she had been named in Romania). She took private lessons in Hebrew and at school studied English and Arabic, focusing on a sciences track, for she felt that there would be more economic opportunities, especially with her interest in architecture. After high school, she was conscripted into the army, and following an unsuitable office work assignment, she worked in the mapping department, more a match to her skills. In 1954, she married a fellow Romanian, Edmond (Eddy) Ernest Granirer, to whom she remained married until his death in 2020. When he completed his military duty, they moved to Jerusalem, where he studied and earned a PhD in Mathematics at the Hebrew University. In that city, Pnina attended the Bezalel School of Art, which taught Applied and Commercial Art in three main departments – Graphics, Metalwork (including jewelry and sculpture), and Weaving. She focused on Graphics, working with instructors who had immigrated from Europe and followed those traditions. Though Pnina and Eddy had little money, “lived on spaghetti,” and worked part-time, they concentrated on their studies and remembered these times as happy. In 1959, Pnina graduated, showing the oil on board painting Ein Karem as a graduation piece. By 1960, their son David Eran was born, and Pnina was able to work from home producing illustrations for books and educational filmstrips for schools.

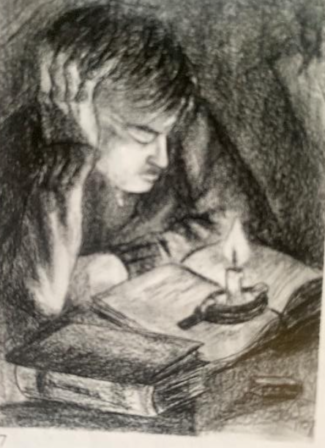

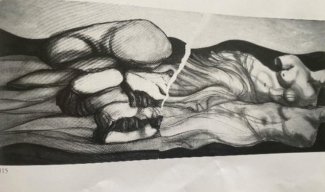

Charcoal on Paper, 60 x 46 cm, 1954

By 1962, there was another immigration for Pnina – Eddy had obtained a teaching position at the University of Illinois (in Urbana) and then two years later, they went to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. The freedom and opportunities in Israel had been so much more than anything in Romania, yet the opportunities for a university position were nil, while jobs opened up in the U.S. when the space race began. Indeed, Pnina was so lucky in her life. Though she initially did not have a visa to work, she was free to do her own art, rather than commercial work, and focused on woodblock prints, drawings, and later watercolours and mixed media compositions. Yet she had to cope with juggling childcare and making the “perfect home” as well as the guilt of not contributing to the finances of the household with her work as an artist. She also realized that with art being taught at universities, there was an intellectualism that seemed unnecessary to her; “theory had replaced passion” in her mind.

Oil on Board, 48 x 69 cm, 1959

From the United States, the Granirers moved to Canada, after her husband was offered a position at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver in 1965. Though she still struggled with doing childcare and housework, their new residence in an old rambling house in Kitsilano had an extra room that she could use as a studio, so she kept going with her art and exhibited in Vancouver and Victoria, drawing on children for subject matter. After another move in 1966 to Montreal, where Pnina worked at Pierre Ayot’s Guilde Graphique and exhibited at the Art Den on Rue de la Montagne, the Granirers returned in 1967 to Vancouver, ending the years of insecurity and constant moves.

Watercolour & collage 68.5 x 75 cm, 1966

With Eddy Granirer’s academic success and position at UBC, the couple was able to buy a house in Point Grey and in 1968 their second son Dan Michael was born. Though her eldest child was in school, Pnina was still caught in the typical female responsibilities of childcare and household demands, which took time away from her work as an artist as well as from making connections with the city’s art world. She valued her family as she prioritized their needs and later had the insight that her work as an artist enriched her family. Her children were a source of inspiration, and in 1969 her monoprint of son David was chosen for the cover of the UNICEF calendar. With her Kite Series she expressed her yearning to fly and break away, though held by a sturdy string. Her children opened her eyes to seeing the magic of the world.

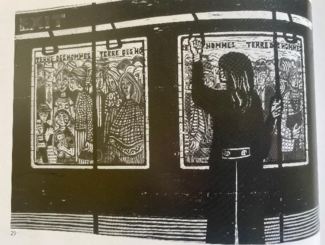

Woodblock & linocut, 45 x 66 cm, 1967

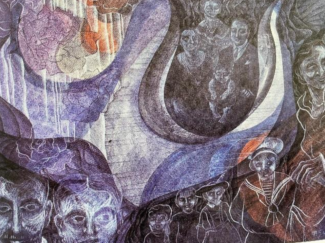

With her Childhood Series, Granirer delved into her own childhood, looking carefully at the childhood devil and angel charms from Romania. By 1974, she had joined the Bau-Xi Gallery, where her work with its fine drawing and intricate designs sold consistently.

As her children became more independent, Granirer became more prolific and varied in her creations. From her home studio with views of the sea and mountains, she first expanded her bird themes with the Wild Goose Series. Not only did she become more aware of the art world in Vancouver, she traveled to Europe, where she amplified her creations with complex patterning reminiscent of historic Middle Eastern traditions. She exhibited The Musical Suite, In the Beginning, and Human Landscapes series at the Bau-Xi Gallery in the 1970s. She was also able to write poetry and descriptions that provided another rich aspect to her work.

She became more interested in West Coast landscapes and Indigenous art, believing that some individuals are attuned to universal forms that can be seen in different times and places. Along with trees, beaches, wildlife, and other natural elements of her coastal home, she melded in the magical and mythical at a time when the public’s awareness of Caucasian appropriation of native cultures was not as strong. After a visit to Haida Gwaii, the rain forests and native culture had an effect on her, expressed in the Cannibal Bird Suite mixed media and paint creations. Her use of Indigenous images were meant to show respect and the acknowledgment of their belonging to the local landscape.

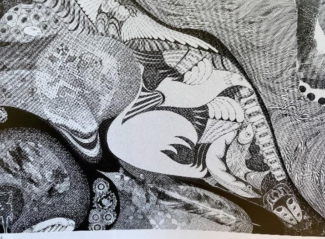

Diptych, India ink on Arches Paper, 75×56 cm, 1975

In the 1980s, Granirer was influenced by the work of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, a huge installation, honouring historically uncelebrated women in the arts and sciences. It led to her Trials of Eve Suite, in which she tussled with Eve as sinner and Adam as unwitting accomplice. In this period, she designed backdrops, banners, and props for the Shakespeare in the Park Festival, creating works in her Stage Series. Theatre can provoke questions about life’s meaning, which she always seemed to be asking. In 1984, Granirer rediscovered an old family album prompting her to delve into life’s enigmas and possible meanings, resulting in The Family Album Suite. In Family, she showed her Romanian family, including her grandparents and her father (as the boy in the sailor suit). At this time her figurative art was unusual in Vancouver, and within two years her relationship with the Bau-Xi Gallery ended because her work was considered “too personal” and “unsaleable.” However, Granirer had a secure life with a supportive and employed husband as well as her own home and studio. She carried on with her interests, only changing when she felt that she has finished with a phase.

Acrylic, transfer, grease pencil, graphite, 56 x 76 cm, 1984

That change occurred in 1985 after visiting friends in Roberts Creek on the Sunshine Coast north of Vancouver and a walk on a rocky beach. She recalled that she had never been particularly interested in stone, but on that day as she sat on a large black boulder, a powerful feeling swept over her. “I understood that this rock upon which I was sitting had been there from time immemorable; it was older than history and had perhaps witnessed events which we will never know. It held mysteries in its silence, stony bosom, stories never to be revealed. I had the extraordinary feeling of a curtain being lifted, allowing me to see the universe unfolding.” This experience initiated The Stone Series. A year later Granirer visited friends on Gabriola Island and was taken by wide deep holes cut for millstones in the natural sandstone landscape, prompting her Millstone Series.

Acrylic, pastel on torn paper, 56 x 129.5 cm, 1987

A 1986-1987 trip to Paris allowed her to revisit the Louvre and with a mature mind see iconic art from a feminist perspective. She began to see stone, such as that used in Winged Victory as in between culture (historically male-dominated) and nature (seen as female, to be dominated). Her study and contemplation of historic art and the rock of British Columbia led to her Culture/Nature series.

In the late 1980s, Granirer was in the exhibitions Fear of Others – Art Against Racism, a logical participation given her past and constant inquiry. Her Invisible Barriers became part of the collection of the United Nations Human Rights Commission in New York City. Her ongoing study of ideas and artistic methods is apparent in in her Emma Lake work (from a 1989 workshop organized by the University of Saskatchewan) where she had to deal with arthritis, particularly in her hands, which meant it was painful to do the detail and precise work of earlier pieces. However, Granirer kept going, freely using brushwork and exploring more with painting. A 1990 trip to Japan opened her eyes to stonework and raked sand in monastery gardens, leading to her Kyoto/Buddha series. Japanese art appealed to her love of architecture, enduring stones, and elements of nature. Her trip inspired her to build a studio at the back of their property, a “room of her own” with north light and a view of Vancouver’s harbour and the mountains beyond.

Acrylic collage, plaster on tarp, 155 x 84 cm, 1987

A trip to Spain in 1992 further stimulated her work, especially at the Alhambra, where Moorish art had thrived. It had been a comparatively tolerant time with opportunities for women, freedoms for Jewish and people of many faiths, and a rich educational and artistic culture. Nature and gardens, especially fountains and water images were inspiring to her as they had been to the Moors. With the later “Reconquista”, Granirer again pondered the “light and dark, good and evil” themes in her quest to understand “life’s origin, possible meaning, and ultimate consequence.”

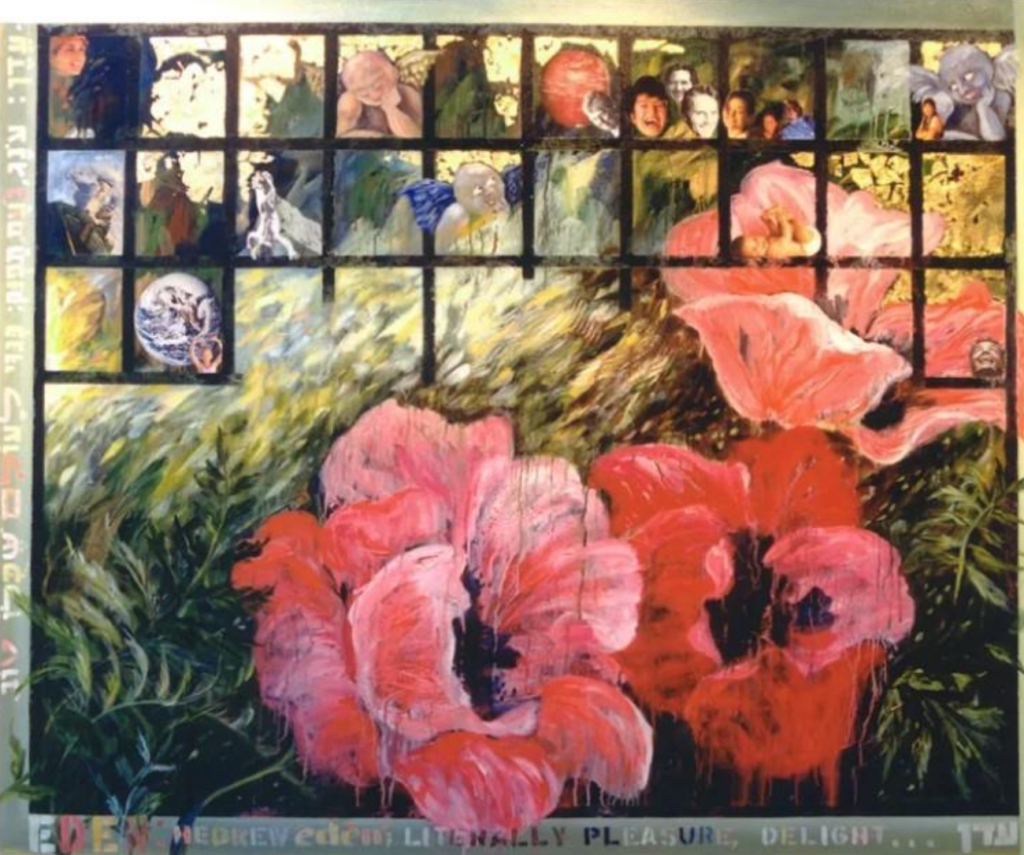

Artists in Our Midst, the first Vancouver communal, annual event of open artists’ studios to the public, was started in 1993 with her friend Anne Adams, initially in three Vancouver neighbourhoods. By then Granirer was teaching through Continuing Education at UBC and was embarking on her In Search of Eden series, often featuring the red poppies seen in Spain. It was a kind of therapy – in spite of darkness and misery in the world, it was important to look at the lighter side and “create our own Edens.”

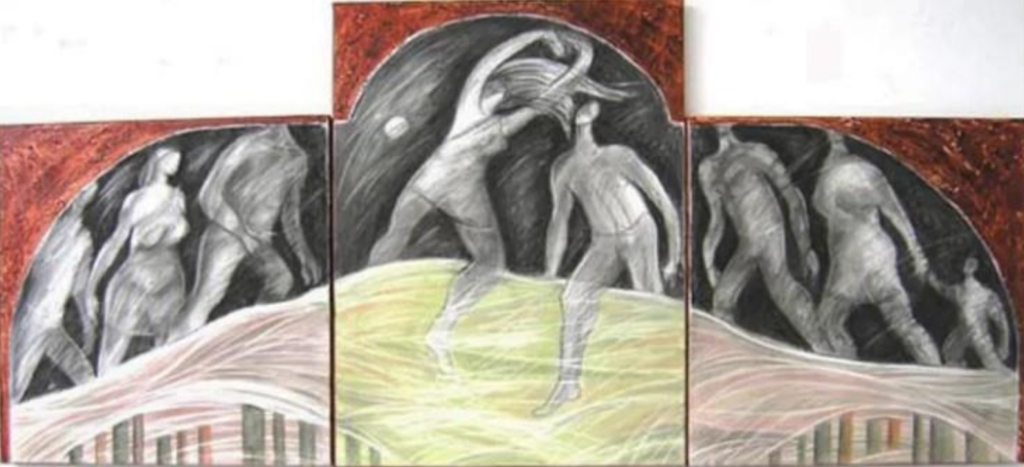

The new millennium did not slow her down. Granirer continued to exhibit her work, most often in Vancouver, and many works featured figures, thus her Figurations of 1999 and In Search of Meaning, where she explored the relationships of men and women. She grappled with the dichotomy of humans needing frameworks for safety and well-being yet longing for freedom from constraining boundaries. Dancers enchanted her and were central to her exhibits at the Ballard Lederer Gallery (2001) and the Seymour Art Gallery (2005) while the Dancers Suite was shown at the Yukon Arts Centre, Whitehorse in 2002. In Gauguin’s Questions Suite she addressed what she called “universal and eternal” questions for all human beings: Where do we come from? Where are we? Where are we going?

Her travel to Guanajuato, Mexico in 2005 led to her 2009 photo-based series of manipulated images and the 2012 Imagination Games exhibit at the Sidney and Gertrude Zack Gallery in Vancouver. Not only was Granirer alive to grappling with profound questions about life and human existence, she was attuned to ever changing technology and artistic media. In Chile, she was included in a show of surrealism, revealing her eclectic creativity, keeping abreast of current tastes and interests.

In the same year as Imagination Games was the Whisper of Stones exhibit at the Two Rivers Gallery in Prince George. It looked to her large body of work, inspired by the geology of B.C. but also to the anguish, love, and inquiry of the human spirit.

By 2017, she had completed Light Within Shadows: A Painter’s Memoir, an exhibition and book, which was launched at the Jewish Book Festival. Originally conceived as a play in three acts (Romania, Israel, and North America), it is a stunning “visual diary” of her life with images and imaginative words. It is a retrospective; yet she is not finished! Her works have been included in shows in Italy as well as numerous galleries in Canada, adding to her international presence. Since the turn of the century, her work has been seen in Spain, Chile, Panama, Argentina, the Netherlands, Israel, France, Czech Republic, USA, South Korea. In 2022, Pnina Granirer produced a new book Garden of Words. Drawing on her wealth of paintings, she has woven words into her works, wishing to “plant a garden of words in her field of colours”. In five chapters she looks again at themes that have touched her life – the stones and sea of her coastal B.C. home, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the rich world of dance, the beauty and heartbreak of Spain’s Moorish period and the reconquest, leading to fear and injustices for people, including those of Jewish heritage. Her final chapter, “This and That,” ranges over deep questions of life, spiritual awareness, and includes a touching elegy to her husband, who had died after sixty-six years of marriage. Here is a woman who has truly loved life, people, and the earth itself.

What an odyssey her life has been! When you think of her beginnings in mid-century Romania and Israel, her narrow escape from perilous situations, and her good fortune, which she has fully utilized, it is one of those stories that can be told again and again. Though she is not on the “full boil” of her most productive years in Vancouver, she is definitely worthy of our attention as she simmers along in her nineties.

*

Christina Johnson-Dean graduated from the University of California, Berkeley (B.A. in History with Art minor) and then trained as a teacher. After three years teaching in public schools, she took her retirement money and traveled around the world, teaching in Thailand and New Zealand, before settling in Victoria. She completed a M.A. in History in Art and served as a teaching assistant as well as creating local art history courses for Continuing Education. Since 1987, she has been teaching in the Greater Victoria School District. Her publications include The Crease Family: A Record of Settlement and Service in British Columbia (1981), “B.C. Women Artists 1885-1920” in British Columbia Women Artists (Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1985) and three titles for Mother Tongue Publishing’s Unheralded Artists of B.C. series: The Life and Art of Ina D.D. Uhthoff (2012), The Life and Art of Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher (2013), and The Life and Art of Mary Filer (2016). In addition, she contributed to Love of the Salish Sea Islands with an article about Gambier Island (2019). [Editor’s Note: Christina Johnson-Dean has recently reviewed the work of Sonja Ahlers, Gary Sim, Robert Amos, and Kathryn Bridge.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Adieu, Pnina! Well, maybe”