Laughing in the face of death

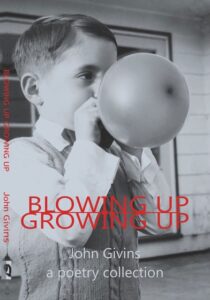

Blowing Up Growing Up

by John Givins

Cambridge: Askance Publishing, 2024

$25.00 / 9781778225062

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

Before there were university Creative Writing departments, there was occasional verse, written to celebrate birthdays, weddings, hangings maybe, the coronations of kings and presidents, the launching of ships, and the birth of children.

If there hadn’t been a twentieth century (or a nineteenth century in French, because, well, Rimbaud) there might have been Occasional Verse departments of instead. Rimbaud would still have gone off to run guns in Africa, sure, but Vancouver-area resident John Givins might be leading graduate workshops in surprise endings, emotional resonance and the wavering line between sentimentality and sentiment, the stock and trade of many global verse traditions, including from the Mediterranean, the Balkans, the Middle East, India, pop music in general and in a retrograde way, any poetry generated by large language model machines.

I say all this to rescue Givins’ work from its most popular contemporary tradition: the humorous (?) birthday card. His is a tradition of stepping past the everyday and honouring hidden patterns. That, and revealing what many are thinking but few have the courage to tell. In other words, it’s the tradition of a court jester.

The point is not to make the jests either particularly deep or funny but to stress the power of the personal, or as Givins says in “New Year’s Eve,”

bragging loud stories of omnipotence

crazy improbable adventures

of lives to be lived

jobs to be explored

marathons to run

waiting for a cab

to an ambiguous new year.

Occasional verse is an ancient tradition. It lives on today among poet laureates, best men at weddings, and MCs at celebrity roasts. All riff off Old Norse traditions of a skjald (a “poet” or “scold”). This speaker is the one character in a feast hall given the right to make fun of a chieftain in order to reveal deeper truths.

Sometimes today scolds tell stories to embarrass (and thus humanize) but not destroy a groom, or stories that stress the abiding character of a bride. Philosophy is not desired. A little blushing drunkenness is not frowned upon.

It’s often power relationships that jesters and fools break open. Among this band, Givins is a happy fool. Of “Two youthful women / laughing, riding on a bicycle / gleefully swerving,” he writes in “Tandem Exuberance,” “getting there / is the best part.”

Givins’ “there” is the end of the poem, where silence reigns. The master, or chieftain, that the scold John Givins is poking is Death. It’s likely also academically-aligned poetry. He does quote Billy Collins in his intro, after all: “Billy Collins said about poetry ‘it doesn’t need to be beaten with a garden hose to get the meaning out.’”

Taking the wind out of Death’s sails (instead of blowing into them) is honourable. Givins poems were written with that kind of honour in mind, written, he says, “as a creative escape during my wife’s marathon trials with colon cancer.” After those trials, she edited them all.

In another tradition, this might have been a book challenging Death and power directly, but that is not the point. These are occasional poems, written in the moment, for the moment. Their theme is their momentariness, as well as their constant search for love and beauty in each and every moment just before it vanishes.

It’s folk poetry. It’s not the kind of verse that will garner a medal from the King’s Court in Ottawa, but it is the kind that can bring a smile as it attests to the joy of human and animal company and asserts the power of connection even when disconnection seems to have the upper hand.

As it closes, the book sets its occasions aside and becomes a book of straight up clowning. In “Pantomime at the Beach,” for example, a pantomime sets up “an invisible umbrella,” then reclines “on his side, / like a Buddha in repose / and with a calm sigh / [falls] asleep.” In “The Clairvoyant Not At the Beach,” having seen “an unusual summer shower” in her crystal ball, a clairvoyant, who had planned to join “her friends the ventriloquist / the pantomime / and the juggler,” stays at home.

Like all clowning, it is a feint at death. Like all clowning, it is bittersweet.

*

Harold Rhenisch has written thirty-four books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for a memoir, The Wolves at Evelyn. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack and Out of the Interior. He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and worked closely with photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass, Motherstone, Cariboo Chilcotin Coast, and The Bowron Lakes; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. His The Salmon Shanties: A Cascadian Song Cycle will appear this fall. Harold lives in an old Japanese orchard on unceded Syilx Territory above Canim Bay on Okanagan Lake. [Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has reviewed books by DC Reid, Kim Trainor, Dallas Hunt, Tim Bowling, Hamish Ballantyne, Zoë Landale, Kerry Gilbert, Robert Hilles, Sho Yamagushiku, Bradley Peters, Aaron Tucker, Dale Tracy, Dominique Bernier-Cormier, Selina Boan, Joseph Dandurand, Délani Valin, Robert Bringhurst, Rayya Liebich, Sarah de Leeuw, Roger Farr, Stephan Torre, Don Gayton, and Calvin White for BCR. His book Landings was reviewed by Luanne Armstrong; The Tree Whisperer was reviewed by Adrienne Fitzpatrick.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster