Humane acceptance (amid absurdity)

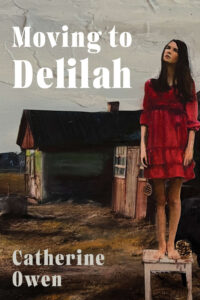

Moving to Delilah

by Catherine Owen

Calgary: Freehand Books, 2024

$19.95 / 9781990601583

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

At first glance, even without the prompts of the cover and the author photo, a casual reader would notice how carefully this book is constructed. Its four sections encompass the poet’s moving from Vancouver to Edmonton, exploring the 1905 house she bought, reporting on her attempts at gardening in a much more hostile climate than Vancouver’s, and finally evoking her growing involvement in the past and present of her new neighbourhood.

But beyond the framework of moving house and nostalgia, what Catherine Owen (Riven) really takes on is not just a house and its history but also the history of the whole city, as evoked, inter alia, by a series of “Postcards from the Archives, 1905.” The postcards enable her to explore issues of identity, love, and loss.

In his groundbreaking essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919), T.S. Eliot memorably asserts that “the historical sense, which we may call nearly indispensable to anyone who would continue to be a poet beyond his twenty-fifth year, and the historical sense involves a perception not only of the pastness of the past but of its presence.” Eliot, I believe, was referring not only to the public past of wars, earthquakes, and governments, but also to personal and family pasts. It is precisely this historical sense that informs Owen’s keen but understated awareness of the interplay between the human world and the natural environment.

We can see this in “The Human Nest,” where the poet finds a hatchling on the sidewalk, considers various options to save it, and finally decides—

there is nothing else to do. Night slits

through and at first light it barely shudders

at touch, too sapped by shock to want.

You won’t look again for a while.

Having fed the chick, “We would take it to the clinic. / It would be saved and our human failures / vindicated for a moment at least.” But after briefly re-entering the house she returns to find the box empty, and the chick gone, presumably eaten by a magpie or a crow: “The birds we hadn’t interrupted sang / and now it was close to evening again.”

Owen’s poetry is bracingly self-aware and without illusions. While sometimes it’s just a throwaway comment, such as “Always overeager for the impossible, me,” she does not shy away from asking herself uncomfortable questions, as in “Two Homes: a Corona,” which begins

Our weird yearnings. But are they?

Is this much nostalgia strange in a world

bent on erasure, elision?

Or again in “The Rasp,” where the wintry sound of sparrows ransacking dead sunflowers reveals her vulnerability in that “the world can still surprise my senses it seems, grief / that never gets waylaid, entirely, by joy.”

Nevertheless Owen’s well developed but unobtrusive sense of humour (look for an instance in “The Thief who Reads Poetry”) seems ready to accept and wryly celebrate any random comforts that come her way, as is evident in her take, in “Mona’s Pub, 118th Avenue,” on the microcosm of a neighbourhood pub after a change in management—

the lengthening tables of laughter, bar-

circled flirtations, kisses even from a random

rapper, compliments from older and older men

The women of mostly mid life, who sling

the drafts and Porn Stars, serve this world

into being: their tender gestures, their fierceness.

The anonymous are now named, the legless lifted

onto stools, the ministry continues, the poison

becomes balm again, the day, night.

These same qualities suffuse final pages written under the shadow of Covid, notably in “Cook County Saloon, October 2020”:

… when they two step.

Except they can’t do that yet—dance—and the crowd

is limited to a century of bodies set apart in table zones,

asked to wear masks. Still, even faced with the echo of death,

the flesh rarely feels like stillness, and couples whirl

in their own worlds…

Her “Pandemic Road Trips 2020” sequence further reminds us how we miss the physical contact, the human touch. In the prose poem “Driving,”

There is nowhere to stop but one gas station

where the cashier (in mask and gloves) allows us to use the sad

bathroom for the price of one pack of Mr Peanuts. Apart from this,

we spot a bison’s head in a ditch, and from a rig, the tattooed

driver nods at me and—almost—I feel young for a moment, as if

touch with a stranger were still possible in the world. And then we,

simply, keep going.

What gives Owen’s poetry its distinctive power is her superb formal accomplishment. Gifted with a poet beachcomber’s eye and ear for language—invented words like ‘ensmalling’ or ‘aura’ used as a verb—she successfully negotiates some of the more demanding traditional verse forms—from villanelle and sestina to pantoum, haibun, and corona—not as acts of bravura but in order to skillfully manipulate them for her own serious purposes.

For me, her technical accomplishment culminates in “New Year’s Eve Feast at the Hotel MacDonald, 2018: a Sestina for Michael.” Owen uses the built-in repetitiveness of the form to meditate on and to re-enact the loss of one relationship that ended in sudden early death and the tentative beginnings of a new one. The poem is a triumph of nuance, balance, and tentative affirmation: “and you / near me now with that ache of newness and promise that / allows me to forget him.”

Apart from the absence of an index, my only problem with the book is that some original ideas, such as those behind the sequence “1905: Four Headlines Each Month on Page One of the Edmonton Journal as Tiny Love Letters,” are taken too far. Likewise, it seems to me that, despite some attractive imagery, the middle section, The Garden, would have been even stronger… with some judicious pruning. Since I have no green thumb, maybe I am prejudiced.

That said, these poems grow on you, for what makes this book, often preoccupied with absence, failure, and insufficiency so rewarding is not only our sense of, and delight in, Owen’s natural unforced sympathy for the marginalized and the outsider, but also the constant interplay of acute observation and comment, so that the poet’s ironic awareness of the absurdity of much human life, which she is content to point out without rancour, is always balanced by a humane acceptance of all its diversity.

*

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. The most recent of his many books of poetry is Moorings, reviewed by Trish Bowering. He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978 and was its editor for a decade; he was Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. [Editor’s note: Christopher has reviewed books by Jess Housty, Susan Musgrave, Katherine Lawrence Leanne Boschman, Isa Milman, H.C. (Hans) ten Berge, John Barton, John Pass, and Rob Taylor for BCR]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Humane acceptance (amid absurdity)”